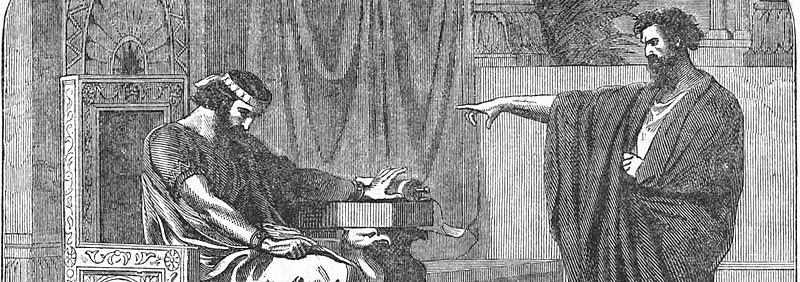

Catholic theology has long grappled with the question of lying on the basis of a certain Scripture passage. In the Book of Exodus, Pharaoh confronts two Hebrew midwives about why the Hebrew baby boys are still surviving even though he’s commanded that the midwives murder them as they are born (an ancient form of partial-birth abortion). The midwives dissimulate, explaining:

the Hebrew women are not like the Egyptian women, for they are vigorous and give birth before the midwife comes to them.” (Exod 1:19 ESV-CE)

The Lord blesses the midwives for their fidelity (v. 20). This lie, or at least near-lie, that the midwives tell becomes a focal point for discussion on the prohibition of lying in the theological tradition. Of course, the Ten Commandments say, “You shall not bear false witness against your neighbor” (Exod 20:16). Later on, the Book of Sirach will make the absolute prohibition on lying even more explicit: “Refuse to utter any lie” (Sir 7:13 ESV-CE).

Fr. Thomas Joseph White, in his Brazos commentary on Exodus states the problem: “Did the midwives lie to the Pharaoh, and if so, is it morally licit to lie in order to save innocent human life?” This ethical problem has been fodder for many a caffeine-fueled, heated theological debate, especially in the wake of the Holocaust. Fr. White relies on Augustine and Aquinas, adopting the view of an “exceptionless prohibition on lying,” but other ethicists, notably Janet Smith, take a different view.

Yet Another Lie

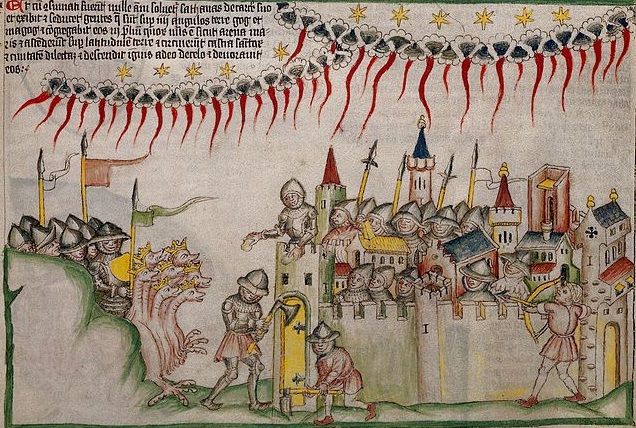

As a Catholic Bible Student, I find it interesting that the discussion centers on the lie of the Hebrew midwives (though Augustine also brings up Rahab’s lie [Josh 2:3-5]). Another example stands out to me as worthy of theological debate–that is the lie of Jeremiah the prophet. Jeremiah is told by the corrupt King Zedekiah to keep his mouth shut. The king wanted to know the real prophecy from the Lord about the fate of Jerusalem, but Jeremiah, fearing for his life, did not want to give bad news to the king so Zedekiah had to coax it out of him by promising him, “I will not put you to death” (Jer 38:16). Jeremiah then gives him the bad news of the coming destruction of the city.

Afterwards, Zedekiah threatens Jeremiah’s life, essentially telling him that if he spills the beans on this private conversation, he’ll be a dead man (Jer 38:24). Zedekiah even gives Jeremiah a line to use with the men who would be curious about his conversation with the king (v. 26). The line goes back to a previous conversation where Jeremiah had pleaded with the king to go home (37:20).

Sure enough, the expected thugs grab Jeremiah by the collar and threaten to kill him if he doesn’t tell them everything from his conversation with the king. Jeremiah dissimulates, offering them the fake line that Zedekiah had given him: “he answered as the king had instructed him.” In short, Jeremiah lies. The lie is not quite as “clean” as the midwives since it’s more of a half-truth. And we’re not told whether God approved of Jeremiah’s lie. However, it is another clear case where a biblical hero tells a lie without negative consequences. He seems to “get away” with the telling of a lie.

While Jeremiah 38:27 is not the focal point of the debate about lying, I did find that the Navarre Bible finds it worthy of an ethical comment:

While Jeremiah 38:27 is not the focal point of the debate about lying, I did find that the Navarre Bible finds it worthy of an ethical comment:

The prophet’s response does not mean that he is deceiving them (they had no right to be party to Jeremiah’s conversation with the king) or that he fears them; we know that his courage was never in question. (Major Prophets, The Navarre Bible, 459.)

This is one way of skinning the cat. It lines up with the first edition of the Catechism, which insisted that “To lie is to speak or act against the truth in order to lead into error someone who has a right to know the truth” (CCC 2483; 1st edition). The definitive Second Edition removes the line about having a “right.”

The Anchor Bible commentary pooh-poohs such ethical discussion: “The oft-discussed point whether Jeremiah is guilty here of telling an untruth is a bit sterile” (Lundbom, Jeremiah 37–52, vol. 21C, Anchor Yale Bible, 78). The ICC also tells us that “Some commentators (especially Duhm; also Cornill and Volz) have wrestled like moral philosophers with Jeremiah’s lie” (McKane, A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on Jeremiah, ICC [1986], 967). Maybe one of these days I’ll rustle up those older commentaries and put some of their moral philosophizing on display. I suppose it’s encouraging that at least someone has thought about whether Jeremiah was lying and if so what that means for us!

So there you have it, a Tale of Two Lies–the midwives and Jeremiah take center stage with Rahab playing a supporting role. Catholic ethicists have fought with each other over these questions and it’s nice to be able to point to another biblical example for analysis, dissection and debate.