Image credit: Fallaner, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

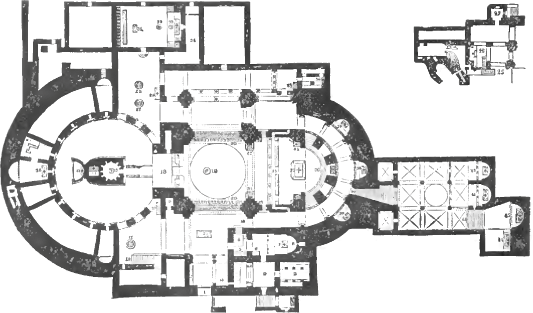

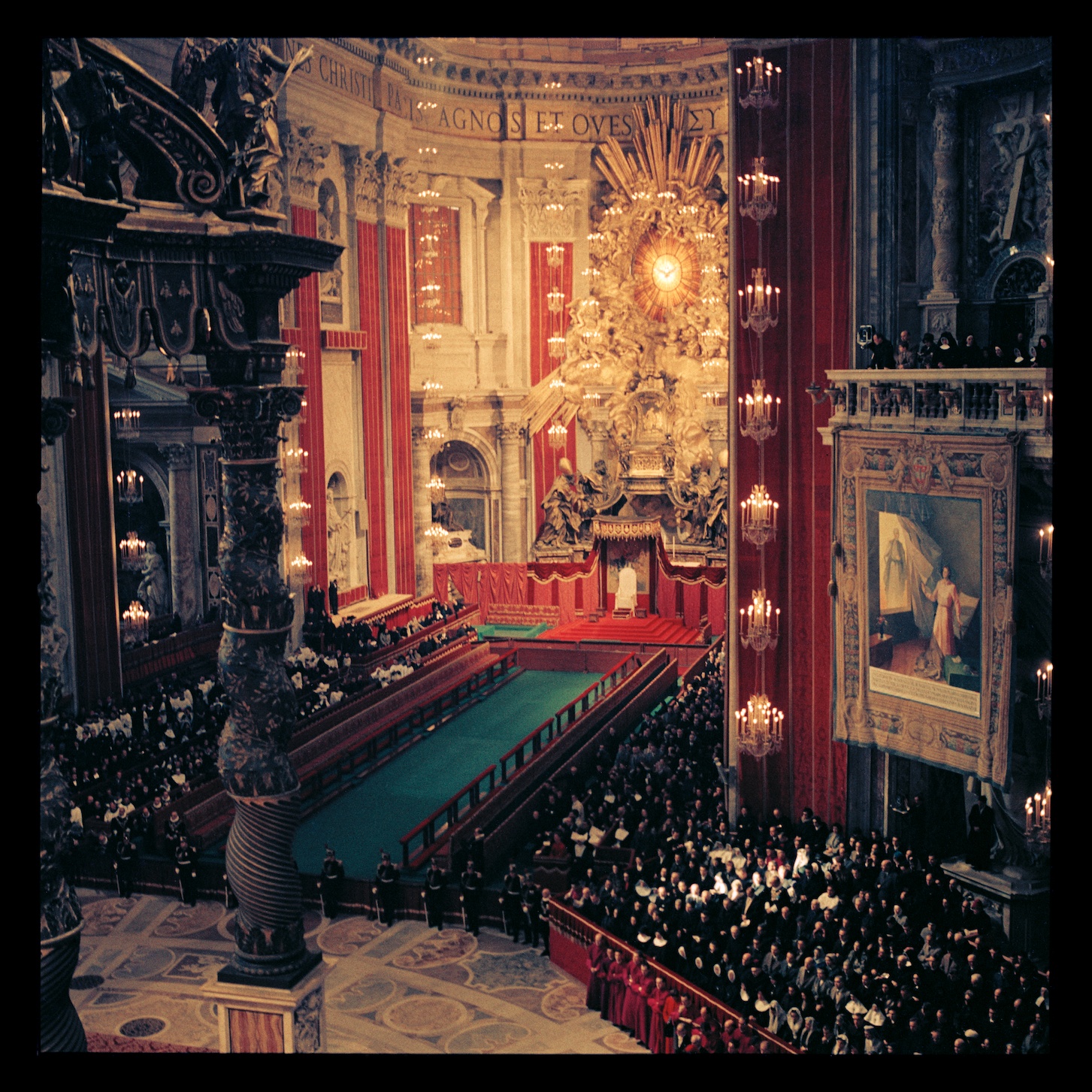

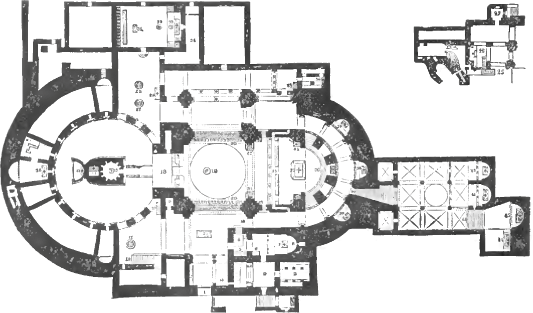

One of the weirdest things that I learned in college is that during the time of St. Cyril of Alexandria, there was a bellybutton statue in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. I saw a circle on a diagram of the church that was labeled “omphalos.” That is the Greek word for bellybutton. I asked my professor what it was about and, if I recall correctly, he explained that it meant that Christians regarded the Church of the Holy Sepulchre as the center of the world. I’ve added a similar diagram here of the modern church and you can see a tiny “19” at the middle. Yes, to this day, the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem has a bellybutton statue at the very center! I’ve also posted a picture of it so you can see what it looks like.

Image from: M’Clintock, John, and James Strong. “Sepulchre of Christ.” Cyclopædia of Biblical, Theological, and Ecclesiastical Literature. New York: Harper & Brothers, Publishers, 1880.

Image from: M’Clintock, John, and James Strong. “Sepulchre of Christ.” Cyclopædia of Biblical, Theological, and Ecclesiastical Literature. New York: Harper & Brothers, Publishers, 1880.

So where did this idea come from? Were there other bellybutton statues in the ancient world? It turns out, there were quite a few.

The Omphalos of Delphi

Image credit: Yucatan (Юкатан), CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

The most famous bellybutton statue was at Delphi where the famous Greek Oracle of Delphi would receive visitors and offer her cryptic prophecies. Some archaeologists think she was inhaling intoxicant vapors from the geothermal features at the site, which helped her achieve an altered state of consciousness for the purpose of prophesying. Some even believe that she breathed these fumes through the omphalos statue itself. Very strange! You can actually still pay a visit to Delphi and find the belly button statue from antiquity in their museum.

Image credit: Berthold Werner, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Outdoors at Delphi, you will also find another bellybutton statue that looks more plain—like a cone of plain rock with no decoration.

The Bellybutton of Rome

Ancient Rome had something similar, called the umbilicus Urbis Romae, the belly button of the City of Rome. It was a statue or monument of a belly button that officially marked the center of the city. It was the point from which all distances were measured. Today it looks a little like a beat up pile of bricks with a doorway:

Image credit: Karlheinz Meyer, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

The Center of the World

The point of all of these belly button statues is that they mark a spot regarded as the “center of the world.” We find this idea in the Bible at the Book of Ezekiel, where the prophet is told,

“Thus says the Lord GOD: This is Jerusalem; I have set her in the center of the nations, with countries round about her.” (Ezek 5:5 RSV2CE)

In fact, many religious traditions identify a certain place as the center to which everything relates. Consider these examples outlined by Zimmerli, Cross and Baltzer:

The wealth of material gathered by Wensinck and Roscher (see also Holma) makes it additionally clear that not only the assertion of living in the center of the world, but also the specific reference to the “navel” (ὄμφαλος) is attested in a wide surrounding area. In Greece, alongside the dominating claim of Delphi, there stands the conception (apparent only in monuments rather than in literature) of the Eleusinian mystery cults that Athens, the μητρόπολις τῶν καρπῶν, was the place of the ὄμφαλος. In the wider Greek world the same claim is made by Paphos, Branchidai, Delos, Epidauros. In post-biblical tradition it gained significance through its connection with the Adam legend in its relationship to Golgotha, Zion and Moriah and perhaps also with Hebron. Islam, for its part, has transferred the tradition to Mecca. (Walther Zimmerli, Frank Moore Cross, and Klaus Baltzer, Ezekiel: A Commentary on the Book of the Prophet Ezekiel, Hermeneia [Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1983], 311.)

So many places have claimed to be the “omphalos,” the belly button or navel of the world. And some of these places mark their claim with a statue of a belly button. The ones we have noticed here include:

- Delphi

- The Church of the Holy Sepulchre

- The Roman Forum