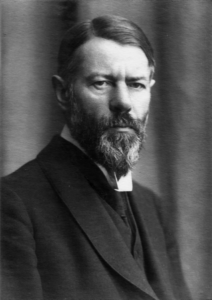

Goran Zivkovic (program chair), James Watts, Naphtali Meshel, Roy Gane, William Gilders, Mark Giszczak (left to right)

A couple weeks ago in Boston I had the pleasure of presiding at a session of the Ritual in the Biblical World program unit of the Society of Biblical Literature Annual Meeting for 2025. The topic under discussion by the presenters was the concept of “ritual indexing” in the thought of Charles Sanders Peirce (pronounced “purse”) and how it can be applied to understanding biblical rituals.

Here’s the official description of the event:

“This session will focus on the interpretation of ritual activities as indexes. Building on the theoretical framework of Charles Sanders Peirce and expanding upon it, this session will primarily explore how ritual actions function to index existential relationships between different ritual elements.”

Rappaport on Peirce

The idea of an “index” is not that complicated. It is “a sign which refers to the Object it denotes by being really affected by that Object” (Buchler quoted in Rappaport). It simply indicates or points to the meaning it is trying to convey. While a ritual action (e.g. eating) might look just like a regular action to an outsider, rituals are constructed to convey deeper meanings. Rappaport gives the following examples:

Thus, a rash indicates (is an index of ) measles, the rustling of the peacock’s spread tail fan indicates his sexual arousal, the weathervane indicates the wind’s direction, the Rolls Royce or sable coat indicates the wealth of its owner, May Day parades indicated the strength of Soviet armaments, or aspects of that strength, the March on Washington of November 15, 1970 indicated the size and social composition of opposition to the war in Viet Nam. (Roy Rappaport, Ritual and Religion [Cambridge, 1999] p. 55)

Presenters and Papers

We had presentations by a group of top-notch scholars working on this concept in the text of Leviticus and the ancient Israelite cult that it prescribes/describes. The papers presented began with “Interpreting Leviticus 1 with Nancy Jay, Charles S. Peirce, and Roy Rappaport” by William Gilders of Emory University. He launched much of this discussion with his important 2004 book, Blood Ritual in the Hebrew Bible, that seeks to interpret the meaning of the blood manipulation rituals of Leviticus. James Watts of Syracuse University presented on “How Indexing Cuts the Gordian Knot of Ritual Meaning,” also using Peirce as mediated through Rappaport to describe how Levitical ritual “indexes” relationships in the Israelite community. Roy E. Gane of Andrews University offered a paper on “Methodology for Analyzing Indexing in Ancient Israelite Cult” along with a very detailed PowerPoint presentation that expanded on how indexing helps us understand Israelite ritual. Lastly, Naphtali Meshel of Hebrew University analyzed the text of Leviticus to reveal ritual indices within the text in his paper, “Ritual Texts Pointing to Ritual Texts.”

It was such a joy to be able to participate in a conversation with these scholars and explore the depth of ritual meaning available in the Levitical system as presented in the biblical text. There is always more to learn and more to study! I look forward to next year’s presentations on Ritual in the Biblical World and I hope that the conversation will continue.