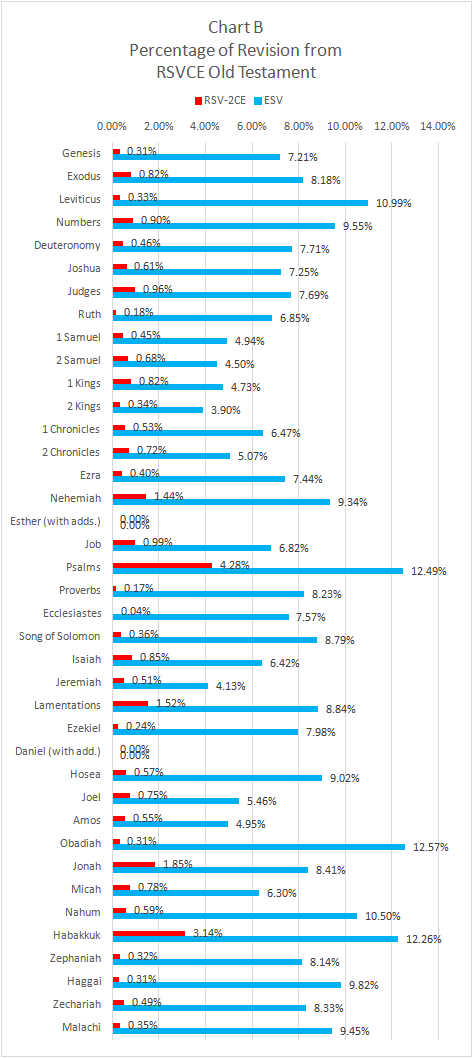

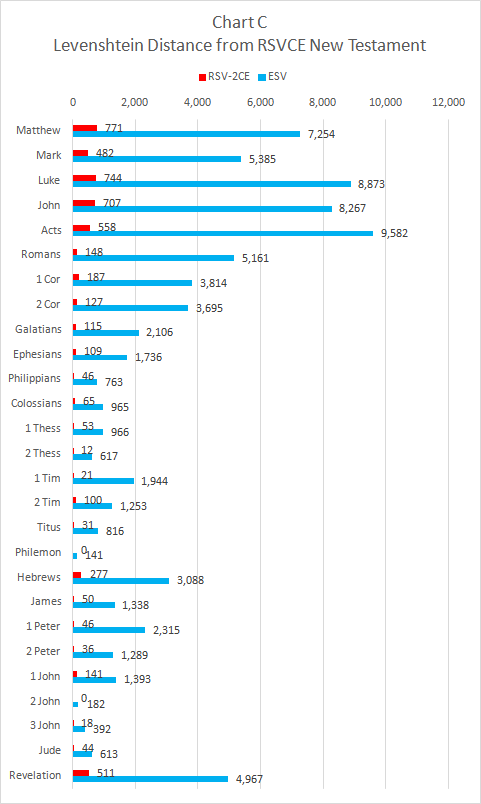

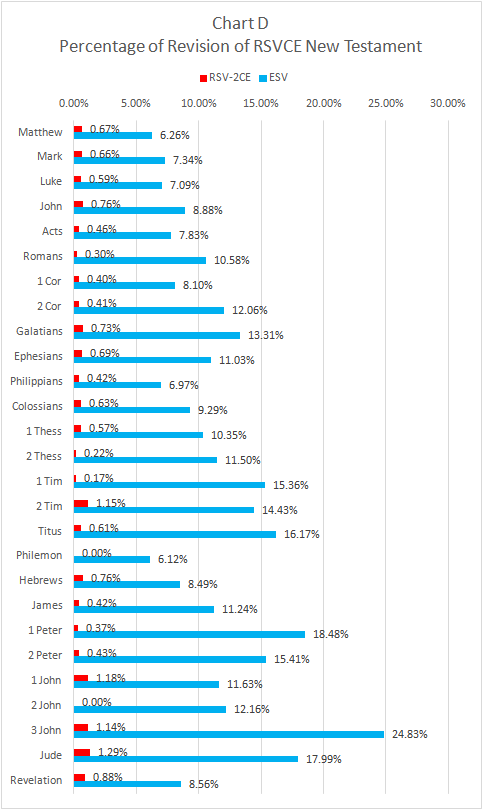

The ESV Bible was originally released by Crossway Books in 2001. This new word-for-word style translation, which was a significant revision of the RSV Bible, has now been adopted by many Christian communities including the Catholic Church in India. Like many translations, the ESV has been released in many different editions. I don’t mean simply hardback, leather and paperback bindings, but that there are actual changes in the biblical text. Over the years, Crossway has published a handful of textual changes and has produced some unusual editions of the ESV for specific audiences—from the English, to the Gideons, to the Catholic Church. In this post, I will list out and explain the editions of the ESV Bible text that have been produced over the years.

2001 First Edition of the English Standard Version Bible

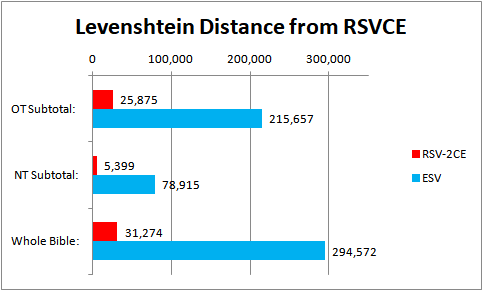

The first edition of the ESV Bible was published in 2001 by Crossway. It was hoped that this new revision of the RSV would replace the KJV, the NRSV and compete with the NIV in the evangelical Bible marketplace. Other translations would soon contend for the same turf: the Holman Christian Standard Bible (2004), the TNIV (2005), the NET (2005) and ISV (2011). The ESV was the product of a serious revision process undertaken in 1998–2001, when Crossway’s Translation Oversight Committee (TOC) held its periodic meetings to hammer out the text that would become the ESV. Its translation philosophy was to modernize the RSV text along the lines of an “essentially literal” approach, aiming for maximum transparency to the original language while maintaining elegant English style.

The first edition of the ESV Bible was published in 2001 by Crossway. It was hoped that this new revision of the RSV would replace the KJV, the NRSV and compete with the NIV in the evangelical Bible marketplace. Other translations would soon contend for the same turf: the Holman Christian Standard Bible (2004), the TNIV (2005), the NET (2005) and ISV (2011). The ESV was the product of a serious revision process undertaken in 1998–2001, when Crossway’s Translation Oversight Committee (TOC) held its periodic meetings to hammer out the text that would become the ESV. Its translation philosophy was to modernize the RSV text along the lines of an “essentially literal” approach, aiming for maximum transparency to the original language while maintaining elegant English style.

2001–2006 Silent Changes to the ESV

The first edition of the ESV was not flawless. In fact, a small number of verses were tweaked after the first edition without any public notification. An example of this phenomenon is in Romans 3:9. Take a look:

- 2001 First Edition ESV: “For we have already charged that all, both Jews and Greeks are under the power of sin.”

- Later ESV: “For we have already charged that all, both Jews and Greeks are under sin.”

The RSV had added the word “power” (not in the Greek) to clarify that people were under the spiritual domination of sin, not physically beneath an invisible entity. That went against the ESV’s “essentially literal” translation philosophy and had to be removed. I would imagine this change was brought to the attention of the TOC by readers familiar with the King James, which does not have “the power of.” These silent changes are small and infrequent, but no one has ever compiled a complete list of them. It would take a monumental effort by someone with eyes like a hawk!

2007 Brings 360 Changes to the ESV Text

Fortunately, Crossway collected ideas for little edits and changes over the years and kept its Translation Oversight Committee meeting on a periodic basis. By 2007, after pastors, churches, professors and seminaries had six years to examine the translation, the TOC released an official, public list of 360 changes to the ESV text, meant to improve the text and bring it further into accord with the ESV’s stated translation philosophy. These textual changes are small and systematic—the “wizards” in the Old Testament became “necromancers”, “reptiles” became “creeping things” (Rom 1:23), instead of “fighting with” we find Jephthah “fighting against” the Ammonites in Judges 11. Some of the changes involve word order, as in Acts 1:3, which had been “To them he presented himself alive,” but is now “He presented himself alive to them.” It is a phrase here and a word there. These minor changes altered the text of the ESV permanently. You can even view these changes through an automated software tool.

2009 ESV with Apocrypha from Oxford University Press

Building on the 2007 ESV Text, Crossway launched a joint publication project with Oxford University Press to bring out the 2009 ESV with Apocrypha. This standalone edition, bound in vermilion hardcover, included the texts of the Deuterocanon, which are in the Catholic Bible:

- Baruch

- Bel and the Dragon (=Daniel 14)

- Greek Esther

- Judith

- The Letter of Jeremiah (=Baruch 6)

- 1 Maccabees

- 2 Maccabees

- The Prayer of Azariah and the Song of the Three Young Men (=Daniel 3)

- Sirach

- Susanna (=Daniel 13)

- Tobit

- The Wisdom of Solomon.

It also included a handful of other texts that are not part of the Catholic Bible, but are regarded as canonical by certain Orthodox Churches, namely

- 1 Esdras

- 2 Esdras

- 3 Maccabees

- 4 Maccabees

- The Prayer of Manasseh

- Psalm 151

This edition laid the groundwork for the ESV-CE since it brought out the texts necessary to include in a Catholic Bible. The tiny one-page preface written by “The Translation Committee of the Apocryphal Books” credits three scholars (David A. deSilva, Dan McCartney, Bernard A. Taylor) and one editor (David Aiken). It is unclear who else, if anyone, was involved in the publication or on the Committee. The ESV with Apocrypha was initially released in just one format, with no electronic editions that I am aware of. Recently, over the past few years (2019–2021), we have seen new editions of it come out from SPCK and Cambridge University Press.

2011 – Another 275 Verses Changed in the ESV Text

In 2011, Crossway released a statement with a new list of changes intended “to correct grammar, improve consistency, or increase precision in meaning.” This list encompassed 275 verses and “less than 500 words.” No more would the Lord be “sorry” that he made man; now he “regretted” it (Gen 6:6). Abraham changes his word order, so he no longer says, “Here am I” but “Here I am.” Now the Apostle John is no longer merely “reclining at table close to” Jesus, but “leaned back against him” (John 21:20). And he asks that the friends be greeted “each by name” now not just “every one of them” (3 John 1:15). These are the kinds of tweaks that scholars love for their precision, but that the typical reader will never even notice.

2012 – Anglicised ESV Bible

One of the virtues of the ESV is that it was designed to be in “Standard English.” That meant the Translation Oversight Committee included both Englishmen and Americans. The text of the Bible should not be nationalized, nor should the English language—though many have tried, going back to Noah Webster and his American Dictionary of the English Language (1828). However, it is true that certain spelling conventions have divided the language across the Atlantic—“theater” or “theatre,” “center” or “centre,” and so on. To deal with this problem, Crossway came up with an “Anglicised” (not “Anglicized”) version of the ESV for publication in England that seeks to offer “British spellings for some words.” It was prepared with HarperCollins UK. The “Collins Anglicised ESV Bible” seems to have originally come out in 2012, but I have not found an official release date. All editions now being published in England through SPCK—whether Anglican, Catholic or otherwise have the “Anglicised” label.

2013 ESV Gideon Edition With NT Based on Textus Receptus

The Gideons are famous for distributing Bibles, placing them in hotel rooms and promoting the reading of the Bible around the world. While they distribute Bibles in many languages, the Gideons used to exclusively distribute the King James Version in English. Then they switched to the New King James Version (1982), but as of 2013, the Gideons have adopted the English Standard Version. This special edition is very different from the regular ESV Text because it uses a different Greek textual base for the translation. “Huh?” you ask. The regular ESV Bible uses the latest critical edition of the Greek New Testament (now the Nestle-Aland 28th edition), while the ESV Gideon Edition uses the so-called Textus Receptus as its base.

The Gideons are famous for distributing Bibles, placing them in hotel rooms and promoting the reading of the Bible around the world. While they distribute Bibles in many languages, the Gideons used to exclusively distribute the King James Version in English. Then they switched to the New King James Version (1982), but as of 2013, the Gideons have adopted the English Standard Version. This special edition is very different from the regular ESV Text because it uses a different Greek textual base for the translation. “Huh?” you ask. The regular ESV Bible uses the latest critical edition of the Greek New Testament (now the Nestle-Aland 28th edition), while the ESV Gideon Edition uses the so-called Textus Receptus as its base.

Why? The Textus Receptus was the Greek base text for the King James Version and some Protestants still hold it in high regard. A great example of the difference is Acts 8:37. If you look it up in the regular ESV, you won’t find it! It’s not there! Ok, it is in a footnote. But if you look up Acts 8:37 in the Gideon ESV, you will find this: “And Philip said, ‘If you believe with all your heart, you may.” And he replied, “I believe that Jesus Christ is the Son of God.” Though the regular ESV is based on more ancient and more accurate Greek manuscripts than the Textus Receptus, it was startling to some English Bible readers to have verses disappear. The Gideons and Crossway reached a compromise agreement, allowing the Gideons to “restore” verses and phrases present in the King James, but not the ESV. The copyright page even says, “Crossway is pleased to license the ESV Bible text to The Gideons, and to grant permission to The Gideons to include certain alternative readings based on the Textus Receptus.” The Gideon edition is the most dramatically different version of the ESV text compared to all other editions, but also the one you’ll never have to pay for!

2016 Permanent Text Edition Changes

In 2016, by this time fifteen years after the original release, Crossway released a final list of changes to the ESV text changing 52 words in 29 verses. The most important change was to Genesis 3:16, which altered God’s speech to Eve from “your desire shall be for your husband, and he shall rule over you” to the more competitive “your desire shall be contrary to your husband, but he shall rule over you.” Both translations are plausible, and the ESV 2016 also changes Gen 4:7 to show the relevance of the change, but with gender issues always being a controversial area, this change did not go unnoticed by critics.

The members of the TOC were aging and the idea of releasing changes on an on-going basis forever seemed implausible. Citing the permanence of the King James Version, Crossway issued the list of changes with a statement that from now on, this would be the “Permanent Text” of the ESV. To me, this strategy seems completely reasonable. Once a book is published, you cannot take it back from readers and rework it, so why keep tweaking a Bible text forever? Weirdly (from my vantage point), Crossway came under attack from certain quarters for issuing a Permanent Text. I really don’t see why anyone would care to stir up controversy over this, but they did. Eventually, responding to critics, Crossway released an additional statement saying that they would be open to “minimal and infrequent” changes to the ESV text.

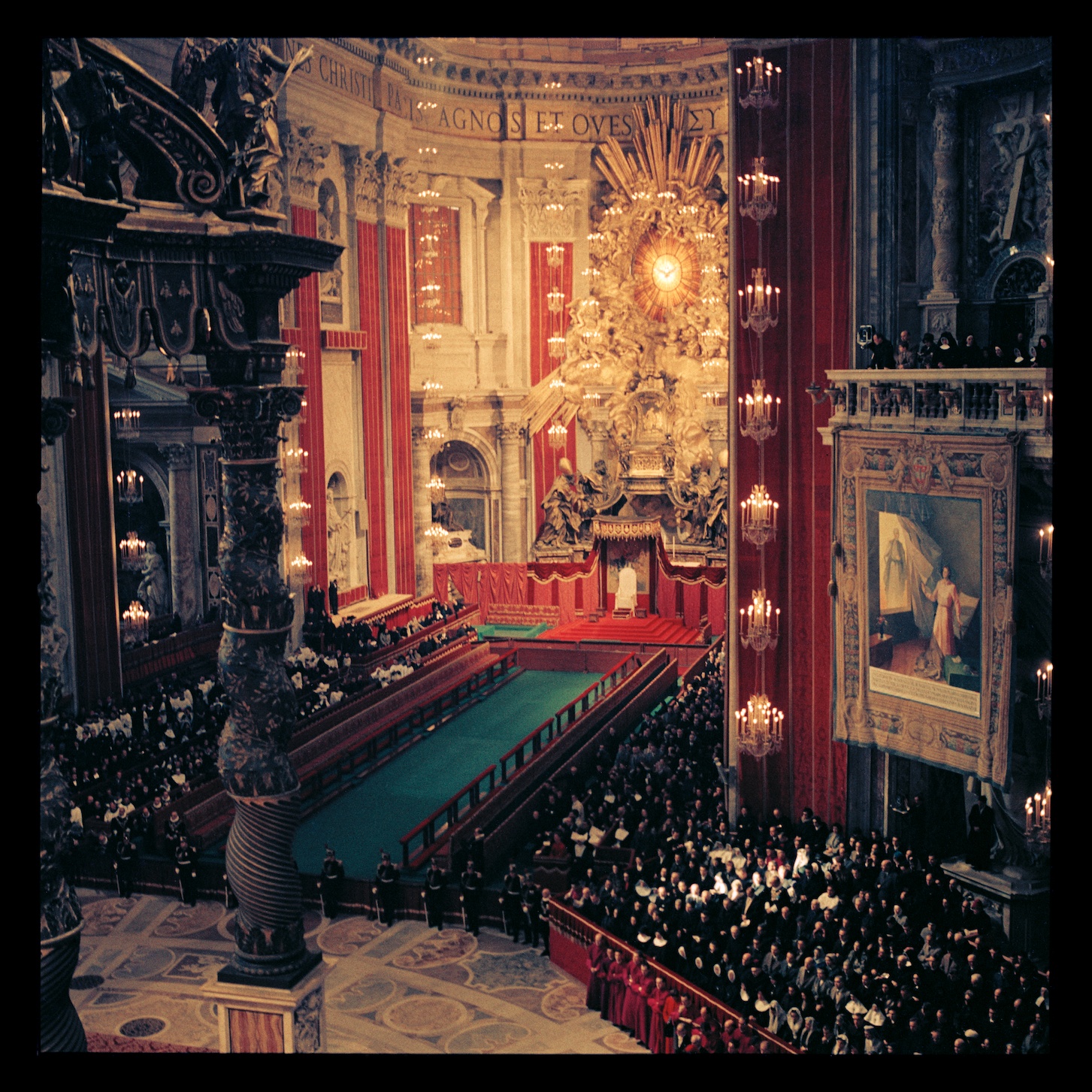

2018 ESV Catholic Edition

In 2018, Crossway published the first edition of the ESV Catholic Edition in combination with the Asian Trading Corporation in India. This edition came to be incorporated in the liturgy in India as part of the 2019 ESV Lectionary approved by the Vatican. The ESV-CE was released by the Augustine Institute in the United States in 2019 as “The Augustine Bible” and it is now under consideration for being adopted in the Lectionary by the bishops of England, Scotland and Wales. If you are interested in learning more about were the ESV came from, its translation philosophy and how it fits in to the landscape of Catholic Bible translations, I have written a whole book about it: Bible Translation and the Making of the ESV Catholic Edition

In 2018, Crossway published the first edition of the ESV Catholic Edition in combination with the Asian Trading Corporation in India. This edition came to be incorporated in the liturgy in India as part of the 2019 ESV Lectionary approved by the Vatican. The ESV-CE was released by the Augustine Institute in the United States in 2019 as “The Augustine Bible” and it is now under consideration for being adopted in the Lectionary by the bishops of England, Scotland and Wales. If you are interested in learning more about were the ESV came from, its translation philosophy and how it fits in to the landscape of Catholic Bible translations, I have written a whole book about it: Bible Translation and the Making of the ESV Catholic Edition

The List of ESV Bible Text Editions

In sum, then, I think we can say that there are at least ten different text editions of the ESV Bible text:

- First Edition ESV (2001)

- Silent Changes ESV (2001–2007)

- 2007 ESV Bible Text

- 2009 ESV with Apocrypha

- 2011 ESV Bible Text

- 2012 Collins Anglicised ESV Bible

- 2013 Gideon Textus Receptus ESV

- 2016 Permanent Text Edition

- 2018 ESV Catholic Edition

- 2019 ESV Catholic Edition, Anglicised