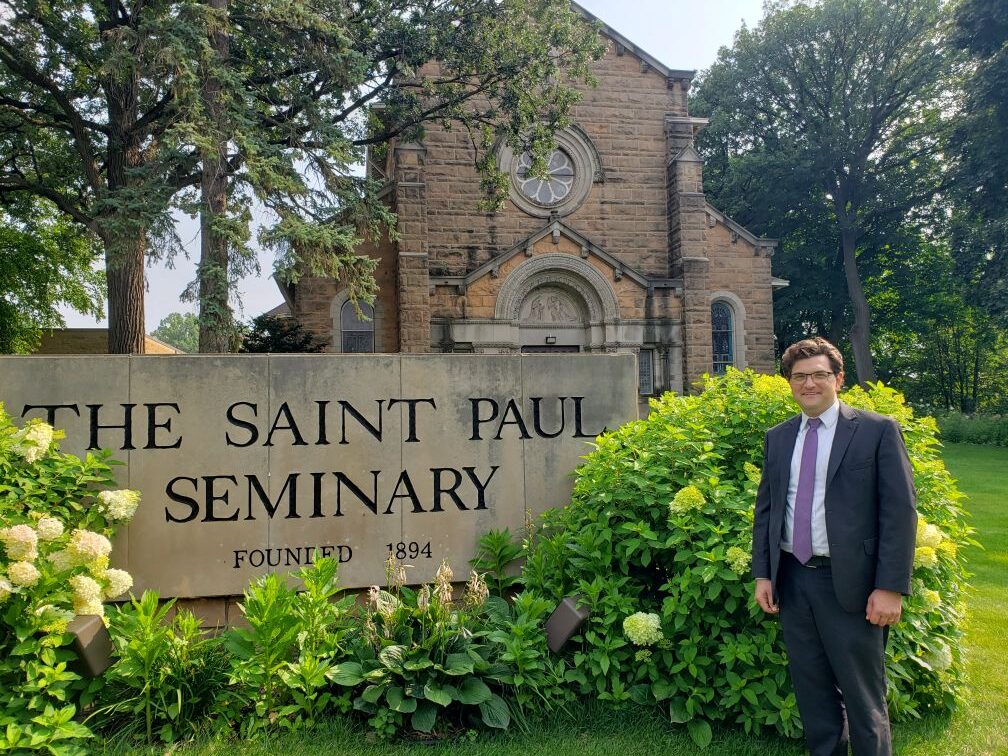

Stephen B. Clark was a giant of the post-Vatican II era in American Catholicism. His name was synonymous with Cursillo, Charismatic Renewal and Covenant Community. I had the privilege of meeting him and interviewing him last year. He died two days ago on March 16, 2024.

Early Life

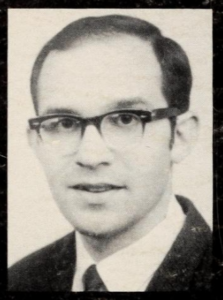

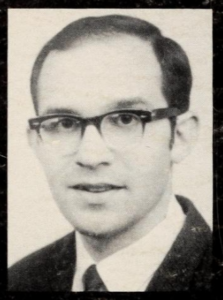

Steve Clark

Steve was born in 1940 to a secular Jewish couple on Long Island. His parents were Louis Seidenstein and Estelle Edna Clark Seidenstein. His only sibling, Joseph, his older brother was nine years older. Steve was a talented student and got a scholarship to the elite Peddie School for Boys. From there, he achieved a full-ride General Motors Scholarship to Yale in 1958. At Yale he studied history and graduated in 1962 at the top of his class with “philosophical orations”–Yale’s equivalent to Summa cum Laude. JFK himself gave the graduation address. During his college years, his father passed away and his mother remarried and moved to Florida.

While at Yale, Steve started reading about Christianity. In particular, The Little Flowers of St. Francis struck him as particularly profound. He was attracted to radical Christianity rather than hum-drum seemingly “normal” Christianity. Soon he approached the student chaplain at the Catholic student center and asked for Baptism. He was baptized around 1960 (though I haven’t been able to pin down the date). He went on a couple summer mission trips to Mexico with the Catholic chaplaincy from Yale and met some people associated with the Cursillo movement from Spain whose faith impressed him. The Cursillo–a “little course” in Christianity–was and is a retreat movement that started in Mallorca in 1949. It had started making inroads in the United States in the 1950s.

Germany (1962–63)

After graduation, Steve went to Germany in 1962 on a Fulbright scholarship to study philosophy–mainly thinkers like Heidegger and Wittgenstein–at Freiburg with such scholars as Fr. Klaus Hemmerle and Fr. Bernhard Welte. He returned to the U.S. in the summer of 1963 and started to pursue a doctorate in philosophy at the University of Notre Dame. That Fall he “made Cursillo” and his life would never be the same. Soon he was teaching other students about Christianity, inviting people on Cursillo weekends and helping organize regular meetings of prayer and discipleship on campus. The cursillistas, as they were called, would have weekly and monthly meetings.

Cursillo and Charismatic Renewal (1964–1969)

By Christmas 1964, Steve had adopted an apostolic vision and vocation. During that break, he convinced one of his Cursillo friends, Ralph Martin (who had graduated from Notre Dame in 1964 and begun studies at Princeton), to drop out of school with him and pursue a life of evangelization and discipleship. The pair went on a long retreat at Mount Savior Monastery in the summer of 1965 to discern for the future. They soon became the “national research staff” for the Cursillo movement in East Lansing, Michigan where they worked closely with Bishop Green, an auxiliary at the time.

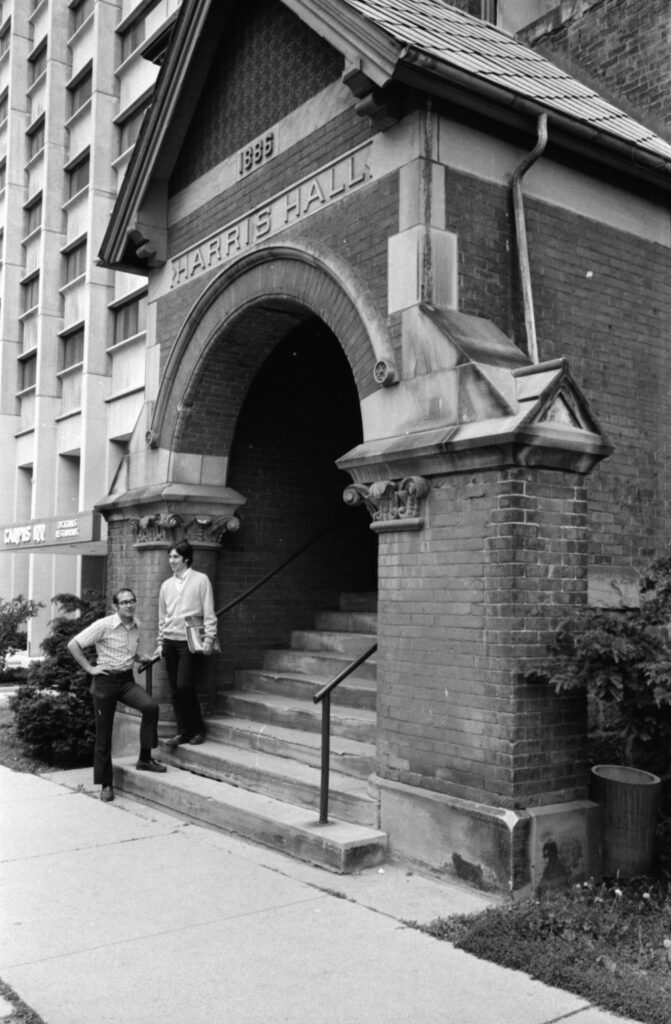

In 1966, Steve read the Cross and the Switchblade by David Wilkerson–a book that he soon passed along to his friends at the national Cursillo convention: Ralph Keifer and Bill Storey. These two theology academics at Duquense University would go on to lead the famous Duquense Weekend, a retreat in 1967 that ignited the Catholic Charismatic Renewal (CCR). Soon after the weekend, Ralph and Steve paid a visit to Pittsburgh to catch the fire. As 1967 rolled on, the CCR spread to Notre Dame’s campus and to Michigan State, where Ralph and Steve were serving. That summer, they were joined by two other ND students: Jim Cavnar and Gerry Rauch. The Four were invited to Ann Arbor by the Catholic chaplain to begin working with students at the University of Michigan there.

Their efforts on campus bore fruit in a prayer group that they eventually built into a “Christian base community” (drawing on ideas from philosophers like Wittgenstein, community organizers like Saul Alinsky, and the 1969 Medillin documents from the Latin American and Caribbean Episcopal Council or CELAM). This ecumenical community came to be known as “The Word of God.” It peaked at about 1,500 adult members in the 1980s. At the same time, Steve devoted his life to being “single for the Lord” and founded an ecumenical brotherhood called The Servants of the Word. This group of celibate men still exists today. During the 1970s, Steve was also deeply involved in what was called the “Shepherding Movement,” an American charismatic movement to regulate Christian life with strong “headship” structures.

The Word of God, the First Charismatic Covenant Community

During these early apostolic efforts, Steve wrote many books and papers in support of the new movements and their ideas, most notably Building Christian Communities: Strategies for Renewing the Church (1972); The Purpose of the Movement (co-authored with Ralph Martin, 1974); and Unordained Elders and Renewal Communities (1976). In Building Christian Communities, he states “Christians are complete only when they belong to a full Christian community, a community in which all the things which are ordinarily needed by anyone to grow as a Christian can be provided” (p. 48). Steve was not only the architect of the Word of God as the first charismatic “covenant community,” but he also was an effective national and international organizer of the movement. In 1975, the CCR had an international meeting at the Vatican and was received by Pope St. Paul VI at Pentecost.

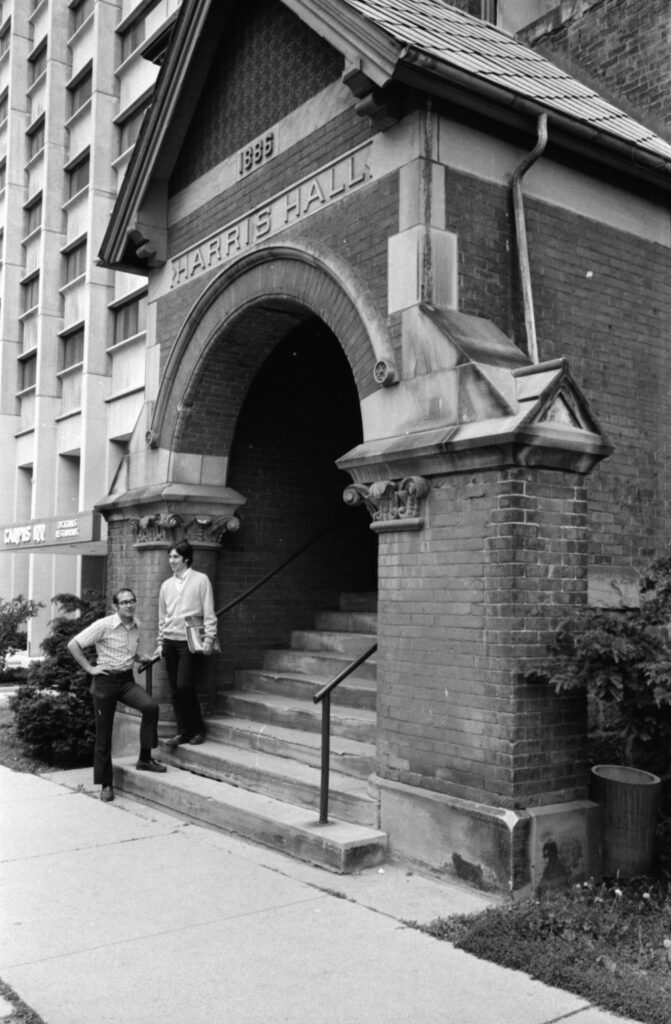

Steve Clark (left) and Ralph Martin at Harris Hall in Ann Arbor, Michigan (photo: Robert Chase, Ann Arbor News, 1974, donated to AADL)

Steve and Ralph moved to Belgium in 1976 at the behest of Cardinal Leon-Joseph Suenens. The Cardinal hoped that they could help establish the CCR in Europe. During these years, Steve organized an international ecumenical federation of covenant communities called The Sword of the Spirit, which boasts about 100 communities and about 10,000 members (though exact numbers are hard to find).

Steve and Ralph moved to Belgium in 1976 at the behest of Cardinal Leon-Joseph Suenens. The Cardinal hoped that they could help establish the CCR in Europe. During these years, Steve organized an international ecumenical federation of covenant communities called The Sword of the Spirit, which boasts about 100 communities and about 10,000 members (though exact numbers are hard to find).

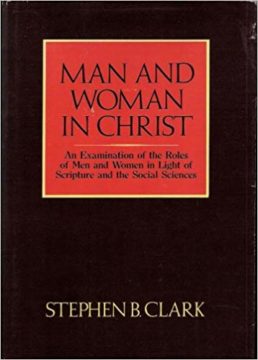

His most notable book, which came out around this time, was Man and Woman in Christ: An Examination of the Roles of Men and Women in Light of Scripture and the Social Sciences (1980). This deeply-researched and lengthy book was Steve’s response to the feminist movement and the changing nature of gender roles in American society. It preceded new developments in the Christian men’s movement like the formation of the Council on Biblical Manhood and Womanhood (1987) and Promise Keepers (1990).

Later Years and Lawsuits

The Word of God community experienced a cataclysmic schism in 1990, with Ralph and Steve going separate ways. That’s another story, but Steve continued as head of the Sword of the Spirit. He wrote additional books like How to Be Ecumenical Today (1996), Charismatic Spirituality (2004), Redeemer: Understanding the Meaning of the Life, Death, and Resurrection of Jesus Christ (1992) and The Old Testament in the Light of the New: The Stages of God’s Plan (2017).

Steve has recently been a defendant in a few lawsuits related to sexual abuse committed by members of the Servants of the Word (additional link from WLNS). Some involved in communities led or inspired by Steve have expressed their hurt and disagreement with his pastoral practices and ideas. See, for example, “Leaving Bulwark” or the many documents critical of Steve Clark and the Sword of the Spirit posted on Scribd by John Flaherty.

Steve Clark’s Legacy

Steve Clark’s legacy will be hard to assess. He certainly influenced many people. As the architect of covenant community, as the leading thinker and community-builder in the CCR, as an ecumenist, as a Christian philosopher-theologian, Steve was not an armchair thinker; he implemented his ideas. Indeed, he gave up the promising future he could have had as a university professor to adopt a radical Christian lifestyle, to disciple other people and to lead a movement. He took concepts of community being discussed in philosophy classrooms and in bishops’ meetings and put them into practice. He connected people around the world to form a coherent movement. He answered the problems of the age with ideas, teachings, practices, communities. He did not just have insight into organizing Christian communities, he taught people how to work together to build a common vision, to “set direction,” and to adopt a common “approach.” His ideas will be important for years to come.

Steve Clark and me