We have all heard that “man does not live by bread alone, but man lives by every word that comes from the mouth of the LORD.” (Deut 8:3 ESV) But this principle is developed further by several texts in Scripture and by quite a few important biblical commentators. For example, we find Ezekiel eating a scroll of God’s words (Ezek 3:3) and again, we find John eating a scroll in Revelation 10:10. Also, the prophet Amos famously says, “Behold, the days are coming,” declares the Lord GOD, “when I will send a famine on the land– not a famine of bread, nor a thirst for water, but of hearing the words of the LORD.” (Amo 8:11 ESV) If we can have a famine of God’s word, then in some way, God’s word is food for us. It is a source of spiritual sustenance. But this idea grows even further.

We have all heard that “man does not live by bread alone, but man lives by every word that comes from the mouth of the LORD.” (Deut 8:3 ESV) But this principle is developed further by several texts in Scripture and by quite a few important biblical commentators. For example, we find Ezekiel eating a scroll of God’s words (Ezek 3:3) and again, we find John eating a scroll in Revelation 10:10. Also, the prophet Amos famously says, “Behold, the days are coming,” declares the Lord GOD, “when I will send a famine on the land– not a famine of bread, nor a thirst for water, but of hearing the words of the LORD.” (Amo 8:11 ESV) If we can have a famine of God’s word, then in some way, God’s word is food for us. It is a source of spiritual sustenance. But this idea grows even further.

For example, Pope Francis delivered a great St. Ephrem quote in his motu proprio today, about the great variety of ways of interpreting Scripture:

“Who is able to understand, Lord, all the richness of even one of your words? There is more that eludes us than what we can understand. We are like the thirsty drinking from a fountain. Your word has as many aspects as the perspectives of those who study it. The Lord has coloured his word with diverse beauties, so that those who study it can contemplate what stirs them. He has hidden in his word all treasures, so that each of us may find a richness in what he or she contemplates” (Commentary on the Diatessaron, 1, 18).

So, I suppose that St. Ephrem here focuses on thirst rather than hunger, but still, it’s the same idea. But wait, there’s more!

St. Thomas Aquinas, in his commentary on the Lord’s Prayer, is talking about the “daily bread” we pray for and explains it like this:

“One may also see in this bread another twofold meaning, viz., Sacramental Bread and the Bread of the Word of God” (Source: Expositio in orationem dominicam)

Pope Benedict XVI, in his apostolic letter, Verbum Domini, points to the hunger and thirst we have for God’s word, relying on Amos:

May the Lord himself, as in the time of the prophet Amos, raise up in our midst a new hunger and thirst for the word of God (cf. Am 8:11). It is our responsibility to pass on what, by God’s grace, we ourselves have received. (sec. 91)

St. Maximus of Turin, in contemplating Jesus’ quotation of Deut 8:3 in Matthew says:

“So, whoever feeds on the word of Christ does not require earthly food, nor can one who feeds on the bread of the Savior desire the food of the world. The Lord has his own bread; indeed, the bread is the Savior himself.” (ACCS, NT Ia, p. 60)

St. Ambrose, in commenting on the manna in the wilderness tells us

“This is the heavenly food…And this is the Word of God which God has set in orderly array. By it the souls of the prudent are fed and delighted; it is clear and sweet, shining with the splendor of truth, and softening with the sweetness of virtue the souls of those who hear it.” (Ambrose of Milan, Saint Ambrose: Letters, ed. Roy Joseph Deferrari, trans. Mary Melchior Beyenka, vol. 26, The Fathers of the Church [Washington, DC: The Catholic University of America Press, 1954], 117.)

St. Gregory the Great offers to parse the distinction between Scripture as food and Scripture as drink:

When the apostles see their souls starved of the food of truth, they nourish them with the banquet of God’s word. And so it is well said: to eat and drink with them, for Sacred Scripture is sometimes solid food for us, and sometimes drink. It is food in the more obscure passages, since it is broken into pieces when it is explained and swallowed after being chewed. It is drink in the more straightforward parts since it is absorbed just as it is found. (Robert Louis Wilken, Angela Russell Christman, and Michael J. Hollerich, eds., Isaiah, The Church’s Bible [Grand Rapids, MI; Eerdmans, 2007], 444.)

Got that? The Scripture food when it is obscure and you have to chew it up before swallowing, but it is drink in the easy, straightforward passages that you only have drink down easily.

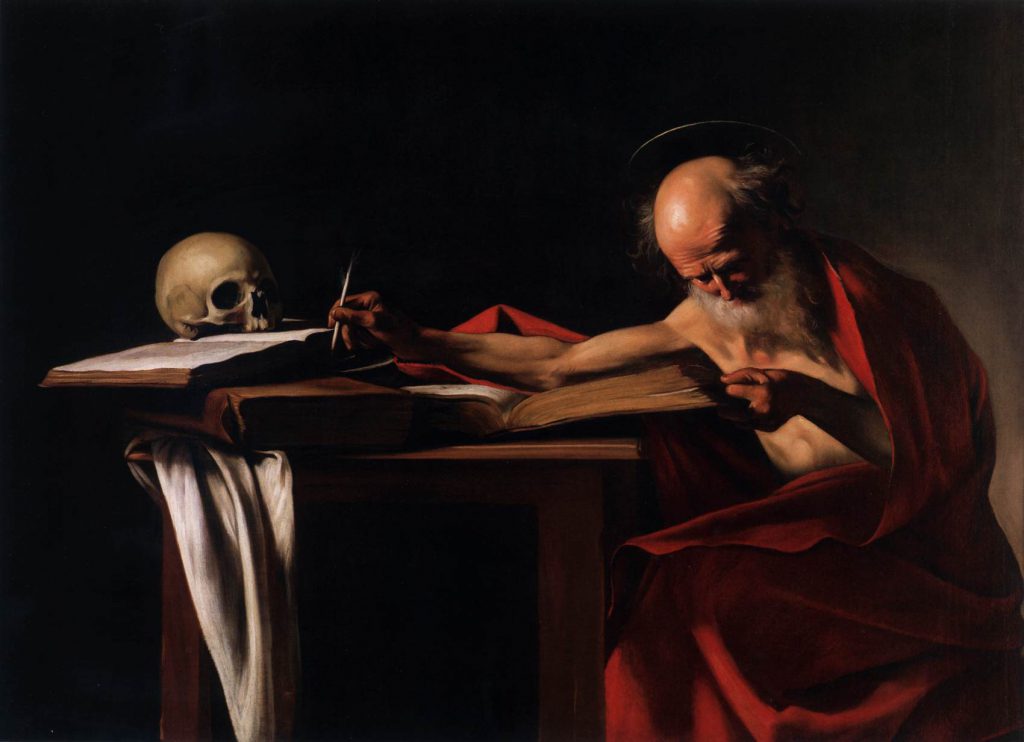

St. Jerome himself insists:

“The flesh of the Lord is true food and his blood true drink; this is the true good that is reserved for us in this present life, to nourish ourselves with his flesh and drink his blood, not only in the Eucharist but also in reading sacred Scripture. Indeed, true food and true drink is the word of God which we derive from the Scriptures” (Commentarius in Ecclesiasten, III: PL 23, 1092A quoted in Verbum Domini, n. 191).

We see in all these comments a shared idea, a common thread: that Scripture is a form of spiritual sustenance akin to the Eucharist. When we read Scripture, we eat Scripture. Of course, we’re not talking about ripping the pages out of your Bible and cooking them up into a stew, but a spiritual eating in which your “soul is satisfied as with fat and rich food” (see Ps 63:5). We have a need–a hunger or a thirst–for God, for spiritual life, for communion. Scripture is given to us in order to satisfy that hunger. So, um, eat up! And Happy Feast of St. Jerome!