Ok, I just came out of a theological rabbit hole of sorts. I suppose it’s trivia, but I thought I’d share it here. The piece of trivia is as follows: that according to St. Bede the Venerable and St. Thomas Aquinas, certain saints receive special heavenly rewards referred to as “aureolae” or “little crowns.” Now it’s important to say that the Catholic vision of heaven is always graded rather than flat. Instead of everyone receiving the exact same level of beatitude, the saints in heaven will vary according to their various virtues and the depth of openness to grace. While “our merits are God’s gifts” (CCC 2009), it is true that according to the Church’s teaching different persons merit at different levels, so Heaven is not a flat land, but a variegated terrain. We see this principle on display in Dante’s Paradiso which describes Heaven as concentric rings, where the holiest saints are closest to God at the center.

The Tradition sets aside certain persons with exceeding merit as special. Indeed, if you flip through the Roman Martyrology, the Divine Office or the Missal, you will find that certain categories of saints receive special types of feasts–most notably, virgins, martyrs and doctors. From ancient times, these three categories of saints were especially honored. Surprisingly, St. Bede finds support for this tradition in Exodus 25:25. I’ll quote the Douay to get closer to the Latin he was reading:

And to the ledge itself a polished crown, four inches high: and over the same another little golden crown. (Exod 25:25 Douay-Rheims)

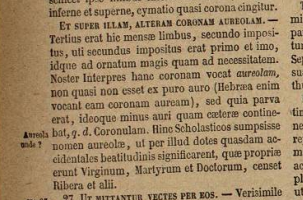

Now this description comes from the instructions on how to build the Table of Shewbread in the original tabernacle. What Jerome called an “alteram coronam aureolam”, most contemporary translations render as something like “a molding of gold around the rim/frame”. The LXX has “a twisted wreath for the crown round about”. The original Hebrew is zer-zahav lemisgarto sabib, which I’ll translate just for fun as “circlet of gold around the border.”

Enough of the text…onto the Interpretation!

Bede offers two different readings—one in a gloss and one in his work, On the Tabernacle. In the gloss, he identifies the “aureolam” of Exod 25:25 with the physical crown that all the blessed will receive when they are reunited with their bodies. This first idea is a general description of the glory which all the redeemed will receive, not a special privilege. However, in the work, On the Tabernacle, he identifies the auroelam as the special honor that will be received by Virgins ([CCSL 119A], Bk. 1, ch. 6).

St. Thomas Aquinas will quote this tradition from Bede:

- On the contrary, on the passage: he shall make another little golden crown (Ex 25:25), a Gloss says: to this crown pertains the new song, which the virgins alone sing together before the Lamb. From this it seems that an aureole is a kind of crown rendered not to all but to some in particular. A golden crown, however, is rendered to all the blessed. Therefore, an aureole is something other than the golden crown. https://aquinas.cc/31/32/~2866 Super Sent., lib. 4 d. 49 q. 5 a. 1 s.c. 1

This same concept shows up in the Summa Supplement 96, which is taken from this chunk of Aquinas’ “On the Sentences”. The main idea is simple: that virgins, martyrs and doctors will receive a special reward, a special aureole or “little crown” which will be a sign of special honor over and above the “aurea” or the crown which every saint receives.

I also found reference to this tradition of the “auoreoles” in Cornelius a Lapide, unfortunately in the untranslated part. Here’s an image:

What’s the Big Deal?

Rather than relegating this idea to the dust bin of ecclesiastical trivia, I think that it helps in a couple ways. One, the aureole actually shows up in Christian art all the time. Whenever you see a virgin, martyr or doctor with a halo in an icon or stained glass, that’s an aureole, a special reward from God for their particular merit. Two, the idea of the aureole helps explain why certain saints are celebrated in certain ways. Doctors of the Church get officially proclaimed by the Pope. Martyrs get red vestments on their feast days. Virgins are celebrated as virgins in the official liturgical texts. While one might question whether such a broad Church tradition can truly be rooted in the text of Exodus 25:25, it is a beautiful example of how Christian interpretation sometimes is more a creative re-weaving of Scripture and Tradition rather than a literal submission of Tradition to Scripture. Not only that, it gives us the etymology for a certain famous bird that is somehow related to baseball.