April 26, 2015

Fourth Sunday of Easter

First Reading: Acts 4:8-12

http://www.usccb.org/bible/readings/042615.cfm

Thank goodness, most of the time we Christians are not on trial. I suppose life can be an ongoing trial and we are tested daily by temptation, but rarely do we actually get dragged before a court of hostile judges who ask probing questions about our faith. It might be worth putting ourselves in the apostles’ shoes, er, sandals, to figure out how we would respond in that moment of true examination.

A Controversial Healing

This Sunday’s first reading picks up where we left off in the story of Acts. In chapter 3, Peter and John heal a man lame from birth in the name of Jesus. Afterwards, Peter gives a speech to the astounded witnesses of the miracle. What always gets me about this healing is that the lame man had been lying there all throughout the ministry of Jesus and yet had never received a healing. He might have witnessed Jesus healing others, but he kept lying there in his disabled state. Yet God picked the right moment for his healing and it was to be at the hands of the apostles. Most sermons end with the preacher sitting back down, but Peter’s incites the “priests and the captain of the temple and the Sadducees” to come and arrest him and John (Acts 4:1).

Tension in the Air

You always know that a homily was worth listening to when the priest is arrested by the authorities at the end of it. However, you would think that healing a lame man would be a universally praiseworthy happening. Everyone should be happy about it, even the Jewish authorities. But the problem is what happened at the recent holiday gathering at Jerusalem—the chief priests, the Sanhedrin, had put Jesus on trial, accused him before Pilate, and brought about his crucifixion. Now that exact same group of Jewish leaders are after Peter and John, two of Jesus’ chief followers.

On Trial Before the Judges of Jesus

Jesus was tried first by Annas, the former high priest who was father-in-law to the current high priest, Caiaphas. (Before and after Caiaphas, five of Annas’ sons also served as high priest.) Then Jesus was tried before Caiaphas and the whole Sanhedrin. When Peter and John are brought before the Sanhedrin, Annas and Caiaphas are there at the head of the judicial body. This group of mostly Sadducee leaders had given a death sentence to Jesus and leveraged their political influence with Pilate to see it through. At that time, John had snuck into Caiaphas’ house to watch the trial, while Peter skulked outside and infamously denied Jesus three times.

Holy Spirit Boldness

However, this time is different. Instead of hiding, sneaking, and denying, Peter stands up with boldness before the Sanhedrin and speaks in the power of the Holy Spirit. This moment fulfills what Jesus had taught the disciples about persecution:

And when they bring you before the synagogues and the rulers and the authorities, do not be anxious how or what you are to answer or what you are to say; for the Holy Spirit will teach you in that very hour what you ought to say. (Luke 12:11-12 RSV)

The Sanhedrin is worried that the Christian “virus” is going to infect the people. In fact, Acts 4:4 tells us that by this point the number of Christians had grown to five thousand, up from three thousand at Pentecost (Acts 2:41). But there is also perhaps a twinge of regret in the question they ask, “By what power or by what name did you do this?” (Acts 4:7 RSV) They don’t directly attack the apostles for healing a lame man, unlike the unrelenting assault on Jesus for healing on the Sabbath, but they do want to know how the apostles have authority to heal. Whether the question is sincere or not does not matter too much, but Peter’s response does.

Being “Saved”

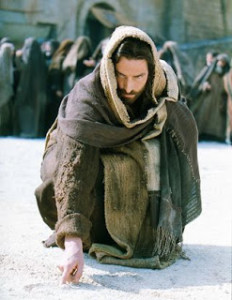

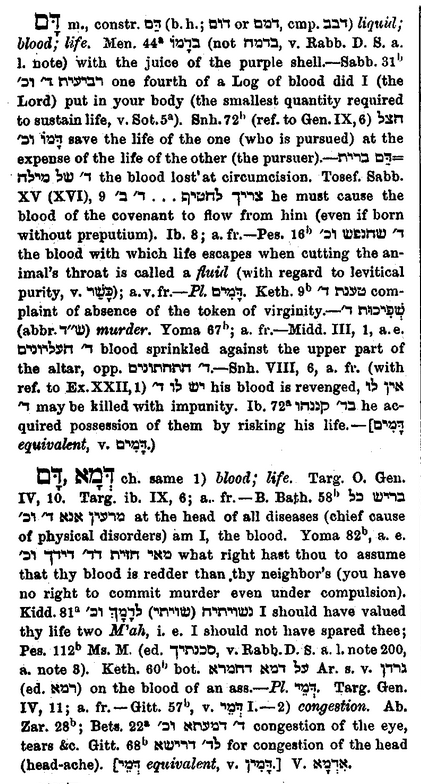

Peter puts the problem starkly, “we are being examined today about a good deed done to a cripple, namely, by what means he was saved” (Act 4:9 NAB). Rather than objecting to the inquiry, he declares “that by the name of Jesus Christ of Nazareth, whom you crucified, whom God raised from the dead, by him this man is standing before you well” (4:10 RSV). Peter uses the same terminology for healing that Jesus does when he tells people he heals, “your faith has saved you” (Luke 7:50; Mark 5:34; Matt 9:22, etc.). This matches the idea of “salvation” just a couple verses later in Acts 4:12. Salvation here in the primary sense is physical healing, which can be expanded to indicate eternal salvation. Peter’s praise report about the man’s Jesus-centered healing also includes an indictment. He accuses the Sanhedrin of crucifying Jesus.

Quoting a Psalm

Peter quotes Psalm 118, a messianic psalm that had come up in Jesus’ ministry. When Jesus rides into Jerusalem on a donkey, the people sing Psalm 118:26 “Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord.” Later, when Jesus is teaching in the Temple, he quotes an earlier verse, Ps 118:22,

17 But he looked at them and said, “What then is this that is written: `The very stone which the builders rejected has become the head of the corner’? 18 Every one who falls on that stone will be broken to pieces; but when it falls on any one it will crush him.” 19 The scribes and the chief priests tried to lay hands on him at that very hour, but they feared the people; for they perceived that he had told this parable against them. (Luk 20:17-19 RSV)

Jesus had just told the Parable of the Wicked Tenants and the Sanhedrin members realize he is accusing them. Peter, before the Sanhedrin, likewise accuses them of being the imprudent builders who reject the most important stone. Not only is the Psalm Messiah-focused, but it also hints at resurrection: “I shall not die, but I shall live, and recount the deeds of the LORD” (Ps 118:17 RSV). Peter points to Jesus as the fulfillment of Psalm 118 and challenges the Sanhedrin for missing the Messiah’s moment and actually bringing about his death.

The bold speech of Peter and John impresses the Sanhedrin and silences them (Acts 4:14). Those who had so virulently accused Jesus while he stood silent are now themselves silenced when listening the proclamation of the gospel of his resurrection. The formerly timid disciples are now proud to identify themselves as Jesus’ followers. While we might not have the opportunity to be put on trial for our faith in such an open and public way, we can learn from the apostles’ attitude. Their faith comes with some swagger, Holy-Spirit-empowered confidence to preach the death-defeating, life-giving message of Jesus. After all, there is no other name…

Almost all prophets have been supported by voluntary gifts. The well-known saying of St. Paul, “If a man does not work, neither shall he eat,” was directed against the swarm of charismatic missionaries. It obviously has nothing to do with a positive valuation of economic activity for its own sake, but only lays it down as a duty of each individual somehow to provide for his own support. This because he realized that the purely charismatic parable of the lilies of the field was not capable of literal application, but at best “taking no thought for the morrow” could be hoped for. (Max Weber, The Theory of Social and Economic Organization [New York: Free Press, 1967] p. 363.)