I was studying this Sunday’s first reading, Wisdom 18:6-9 while working on my weekly column and noticed something rather odd: The second half of Wisdom 18:9 is simply missing from the text. The full verse in the NAB is:

For in secret the holy children of the good were offering sacrifice

and carried out with one mind the divine institution,

So that your holy ones should share alike the same blessings and dangers,

once they had sung the ancestral hymns of praise.

Yet the English Lectionary only includes:

For in secret the holy children of the good were offering sacrifice

and carried out with one mind the divine institution,

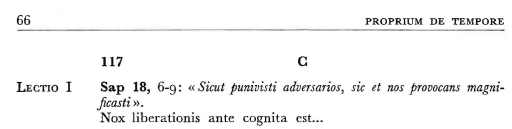

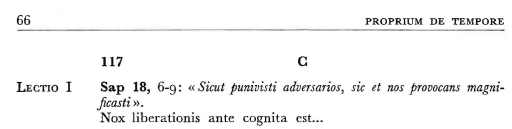

Now, often the Lectionary will include partial verses, but they are always indicated by a letter, so you might have Gen 18:1-10a, for example. But in this case, there is no letter indicated by the verse reference. I thought this mystery might call for a little Catholic Bible Student investigation, so I dug up a copy of the Ordo Lectionum Missio, editio typica altera from 1981. This is the official Latin listing of the Lectionary readings. And sure enough for Lectionary #117, Wisdom 18:6-9 are listed not 18:6-9a.

The abbreviation “Sap” is for “Sapientia,” Wisdom. After seeing this, I thought that the difference might be in the versification of the Nova Vulgata, on which the 1981 Lectionary is based. But no, the verse appears in full in the Nova Vulgata:

Absconse enim sacrificabant iusti pueri bonorum

et divinitatis legem in concordia disposuerunt;

similiter et bona et pericula recepturos sanctos

patrum iam ante decantantes laudes. (Wisdom 18:9)

You’ll also notice that the Ordo Lectionum also gives an “incipit” (Nox liberationis…) that clarifies the subject of the first line by adding a single word and omitting the first word of verse 6.

But in the end, we’re left with a puzzle. Why would Wisdom 18:9b be omitted from the reading in the English translation? Here are possible theories: (a) the Latin Lectionary actually omits the lines and the English translators followed suit, (b) the English translators made a mistake by omitting them, (c) the lines struck the English translators as problematic, so they deliberately omitted them. If we go with Theory C here, I still don’t understand why the lines would be problematic–perhaps because they mention the fact that the saints will share in dangers as well as good things?

Yet many other parts of Scripture talk about us sharing in suffering, so I can’t think that’s the issue here. In fact, the lines are included in the Spanish edition of this reading. I’d be curious to look at Lectionaries in other languages to see if these lines are present or omitted, but for now we’ll have to chalk this one up as a mystery!

Owl image credit: By Athene_noctua_(portrait).jpg: Trebol-a derivative work:Stemonitis (Athene_noctua_(portrait).jpg) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons