Colossians 3:11 gives us one of Paul’s lists of formerly-significant people boundaries to indicate that now in Christ, we are all one and these boundaries no longer matter. The text reads:

Here there is not Greek and Jew, circumcised and uncircumcised, barbarian, Scythian, slave, free; but Christ is all, and in all. (Col 3:11 ESV)

ὅπου οὐκ ἔνι Ἕλλην καὶ Ἰουδαῖος, περιτομὴ καὶ ἀκροβυστία, βάρβαρος, Σκύθης, δοῦλος, ἐλεύθερος, ἀλλὰ [τὰ] πάντα καὶ ἐν πᾶσιν Χριστός.

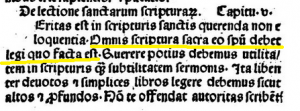

Unfortunately, the very last part of the verse always sounds weird. I mean, “Christ is all”–what does that mean? The translations do not deviate much from this line. I’m sure that lots of translators have toiled over this verse, so I don’t mean to scoff at their hard work or claim any sort of omniscience. I merely want to make a suggestion. The copula, the verb of being, is absent in the Greek and therefore always inserted in the translations. Latin can follow the Greek without an “is”: “…sed omnia et in omnibus Christus.” If all I had was that snippet and no context, I’d be very tempted to translate either the Latin or Greek as “…but all and in all, Christ” or “…but all and Christ in all.” So, why not translate the verse that way?

To me it seems that list of divisions Paul rattles off between Greek and Jew, slave and free and so one simply terminates at panta, all. Let’s try another sentence with the same structure to see if this could work: “Here there is no longer short and tall, big and small, serious and silly, but everybody and in everybody is ice cream.” Doesn’t it seem that the final term in my list, everybody, could function as the terminus of the list rather than as a predicate nominative of “ice cream”? “Everybody is ice cream” sounds strange.

To me it seems that the drive to translate our phrase as “Christ is all and in all” comes from the context and the idea of putting on Christ and especially “Christ who is your life” in verse 4. But it really seems like an unnecessary stretch. Why does the adversative, alla, but, have to create a new independent clause, couldn’t it just be Paul’s way of punctuating the turning point in the comparison?: Before, we had all kinds of divisions that divided us, but now we are one. Lastly again, it comes back to trying to make sense of the “Christ is all” statement. What does that even mean? Paul is certainly not pantheist or something, so what could such a statement convey, that every Christian is in some mysterious way, Christ?? I’d prefer that Paul is simply saying in Christ, the divisions fall away and only “all/everybody” is left and in everybody dwells Christ. That seems to fit the grammatical demands and Paul’s theology. Inserting an “is” to me seems an overly creative translation twist.

(Of course, perhaps I’m overlooking something important, so please comment if you can explain why “Christ is all” is the best translation here.)

You might be surprised when you’re reading the New Testament and a verse disappears into thin air. For example, if you are reading Acts 8:36, you would expect Acts 8:37 to follow, but oddly, 8:38 is the next verse. What happened to Acts 8:37?

You might be surprised when you’re reading the New Testament and a verse disappears into thin air. For example, if you are reading Acts 8:36, you would expect Acts 8:37 to follow, but oddly, 8:38 is the next verse. What happened to Acts 8:37?