When I tell people about the new ESV Catholic Edition Bible, many of them ask me how it is different from the RSV-2CE. Now, that might leave you scratching your head thinking, “I’ve heard of the RSV and even the NRSV, but what is the RSV-2CE?” So just a bit of backstory before we get to the statistical comparison of the ESV-CE and the RSV-2CE…but here’s a sneak peak at the results:

Backstory

The RSV, which is a revision of the so-called “Standard Version,” aka ASV, came out as New Testament only in 1946 and in full in 1952. But not exactly. That is, the 1952 version only included the books in the Hebrew Bible, not the books in the deuterocanon. It was a Protestant edition, but even so, the translators kept working and released “The Apocrypha” in 1957, which included the deuterocanon. Fair enough, but Lutherans and Anglicans use the deuterocanon, so it was still a Protestant translation until 1965-66 when the “RSV Catholic Edition” was approved in England and released.

The RSV, which is a revision of the so-called “Standard Version,” aka ASV, came out as New Testament only in 1946 and in full in 1952. But not exactly. That is, the 1952 version only included the books in the Hebrew Bible, not the books in the deuterocanon. It was a Protestant edition, but even so, the translators kept working and released “The Apocrypha” in 1957, which included the deuterocanon. Fair enough, but Lutherans and Anglicans use the deuterocanon, so it was still a Protestant translation until 1965-66 when the “RSV Catholic Edition” was approved in England and released.

If I haven’t lost you yet, at the same time that the Catholic Edition was getting approved, the RSV Protestant Edition New Testament was undergoing a revision and that revised Protestant-only RSV NT, the RPRSVNT for short (just kidding), came out in 1971. The translation committee started moving toward a revision of the Old Testament, but that project never materialized. Instead, the Committee turned its attention to the NRSV, which took the place of the RSV in 1990. However, a lot people were not very happy with the NRSV, which is a story for another time. They kept reading their RSV Bibles.

The ESV and the RSV-2CE

Yet even those Bible readers who loved the RSV felt like it needed a touch-up. Two different groups, one Protestant and one Catholic, went back to the RSV to revise it again, but in a different way than the NRSV. Crossway Books, a Protestant publisher, started first in 1999 and completed their revision in 2001—that’s what we now know as the ESV. Ignatius Press, a Catholic publisher, started soon after and published the RSV-2CE in 2006. Now, of course my readers will know, the ESV-CE exists as of 2018. So, how are these two different revisions of the RSV different from one another?

Yet even those Bible readers who loved the RSV felt like it needed a touch-up. Two different groups, one Protestant and one Catholic, went back to the RSV to revise it again, but in a different way than the NRSV. Crossway Books, a Protestant publisher, started first in 1999 and completed their revision in 2001—that’s what we now know as the ESV. Ignatius Press, a Catholic publisher, started soon after and published the RSV-2CE in 2006. Now, of course my readers will know, the ESV-CE exists as of 2018. So, how are these two different revisions of the RSV different from one another?

A Personal Note

It is important to say that though I find myself wrapped up in the publication and promotion of the ESV-CE, I like the RSV-CE and the RSV-2CE as well. In fact, my own writing has appeared and will continue to appear along with the RSV-2CE in publications like the Ignatius Catholic Study Bible and the Augustine Institute’s Bible-in-a-Year. I really just want people to read, study and pray the Bible, regardless of whatever translation or language they are reading it in.

It is important to say that though I find myself wrapped up in the publication and promotion of the ESV-CE, I like the RSV-CE and the RSV-2CE as well. In fact, my own writing has appeared and will continue to appear along with the RSV-2CE in publications like the Ignatius Catholic Study Bible and the Augustine Institute’s Bible-in-a-Year. I really just want people to read, study and pray the Bible, regardless of whatever translation or language they are reading it in.

First, the Similarities

- Both the RSV-2CE and ESV-CE have all the books of the Bible including the deuterocanon.

- Both the RSV-2CE and ESV-CE are revisions of the RSV Bible.

- Both the RSV-2CE and the ESV-CE eliminate archaic language that was included in the RSV: thou, thee, didst, hast, etc.

Second, the Differences

- They have different base texts for the New Testament: The RSV-2CE, being a revision of the 1965-66 RSV-CE, starts with the 1946 RSV New Testament with the few dozen minor modifications made by the Catholic translators (listed in the back of the RSV-CE). The ESV-CE, because it started as a Protestant revision of the Protestant RSV, drew on the 1971 RSV New Testament, not the 1946 New Testament. The ESV-CE thus has one additional layer of updates in the New Testament.

- The RSV-2CE is minor revision, while the ESV-CE is a major revision. Maybe one way to put it is the RSV-2CE is still the RSV. The number of changes is very small and the scope of changes is modest. A large number of the RSV-2CE changes involve updating language to get rid of “thees” and “thous.”

- The ESV-CE is based on updated text-critical information both in the Old and New Testaments, whereas the RSV represents the state of the field in the 1940s and ’50s. Two facts illustrate the point:

- The RSV used the 17th edition of the Nestle-Aland critical edition of the Greek New Testament, while the ESV used the 27th Text-critical knowledge of the text of the NT has improved considerably since the 1940s.

- The RSV-2CE of Tobit relies on the 1957 RSV Apocrypha translation, which was based on the shorter Greek text of Tobit (Greek I represented in Vaticanus and Alexandrinus), while all modern translations of Tobit, like the ESV-CE, rely on the longer Greek text (Greek II represented by Sinaiticus). Greek II is about 1700 words longer than Greek I and it serves as the basis for the Nova Vulgata rendition of Tobit in Latin. Greek II is also confirmed as the best text of Tobit by the 1995 publication of long fragments of Tobit from the Dead Sea Scrolls in Hebrew and Aramaic by Fr. Joseph Fitzmyer, SJ.

Statistics, Please!

Ok, now the fun part. To illustrate that the ESV-CE is a major revision and the RSV-2CE is a minor revision, one only needs a computer. Rather than reading through the entire Bible and hand-counting every single change, I decided to let the robots do the hard work. But how? By using a little-known idea from computer science called “Levenshtein Distance,” which quantifies “the number of deletions, insertions, or substitutions required” to change one string of text into another string of text.

Methodology

Using the “Bible Text Only” copy tool in Verbum (aka Logos) Bible Software which excludes verse numbers, headings, footnotes and other non-Bible text, I compared the RSV-CE text of every book of the Bible to the RSV-2CE and to the ESV-CE to calculate the Levenshtein Distance as a discreet number, using the calculator at PlanetCalc. Then dividing the Levenshtein Distance by the total number of characters in the RSV-CE text, I was able to arrive at a percentage difference between the RSV-CE and the RSV-2CE, and also the percentage difference between the RSV-CE and the ESV-CE. (Yes, this took a long time and a huge spreadsheet!)

For example, using the super-short Obadiah, we find 3,221 characters in the RSV-CE. The RSV-2CE Levenshtein Distance for Obadiah is only 10, so we have a 0.31% difference. Whereas, the ESV-CE Levenshtein Distance for Obadiah is 405, revealing a 12.57% difference—a far more substantial revision. What I will list in the following tables is the percentage difference from the RSV-CE for every book of the Bible both in the RSV-2CE and in the ESV-CE and the Levenshtein distance for every book of the Bible, comparing both translations. Before we get there, another example might help.

Example: Deuteronomy

Here’s the data for Deuteronomy:

- RSV-CE Bible text characters: 141,082

- RSV-2CE Bible text characters: 141,025

- RSV-2CE Levenshtein Distance from RSV-CE: 654

- ESV Bible text characters: 140,039

- ESV Levenshtein Distance from RSV-CE: 10,883

To get percentages, we use Levenshtein Distance divided by RSV-CE characters:

|

Deuteronomy: |

RSV-2CE | ESV | ||

| Levenshtein Distance: | 654 | Difference:

0.46% |

10,883 |

Difference: 7.71% |

| RSV-CE characters: | 141,082 |

141,082 |

||

This example illustrates how the ESV is a major revision of the RSV, while the RSV-2CE is a minor revision. The ESV has more than sixteen times as many changes as the RSV-2CE in Deuteronomy.

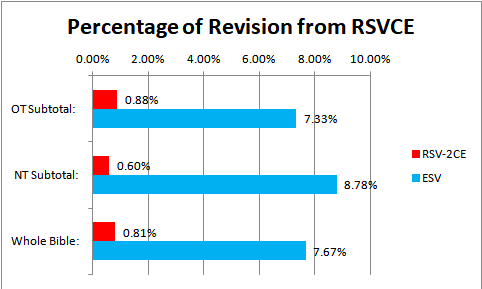

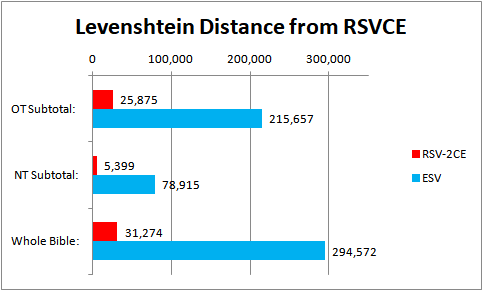

Results: Old Testament, New Testament and Whole Bible in tables and charts

|

Old Testament: |

RSV-2CE | ESV | ||

| Levenshtein Distance | 25,875 | Difference:

0.88% |

215,657 |

Difference: 7.33% |

| RSV-CE characters | 2,940,837 |

2,940,837 |

||

|

New Testament: |

RSV-2CE | ESV | ||

| Levenshtein Distance | 5,399 | Difference:

0.60% |

78,915 |

Difference: 8.78% |

| RSV-CE characters | 898,327 |

898,327 |

||

|

Whole Bible* |

RSV-2CE | ESV | ||

| Levenshtein Distance | 31,274 | Difference:

0.81% |

294,572 |

Difference: 7.67% |

| RSV-CE characters | 3,839,164 |

3,839,164 |

||

*It is worth noting that I’m working from what’s available in the software, and right now that is the ESV-2016, not the current ESV-CE, so my calculations do not yet include the deuterocanonical books (or Esther and Daniel), nor the very few changes have been made between the Protestant and Catholic versions of the ESV.

Overall, we see that the ESV has nine-and-a-half times more changes than the RSV-2CE.

Results: Book by Book

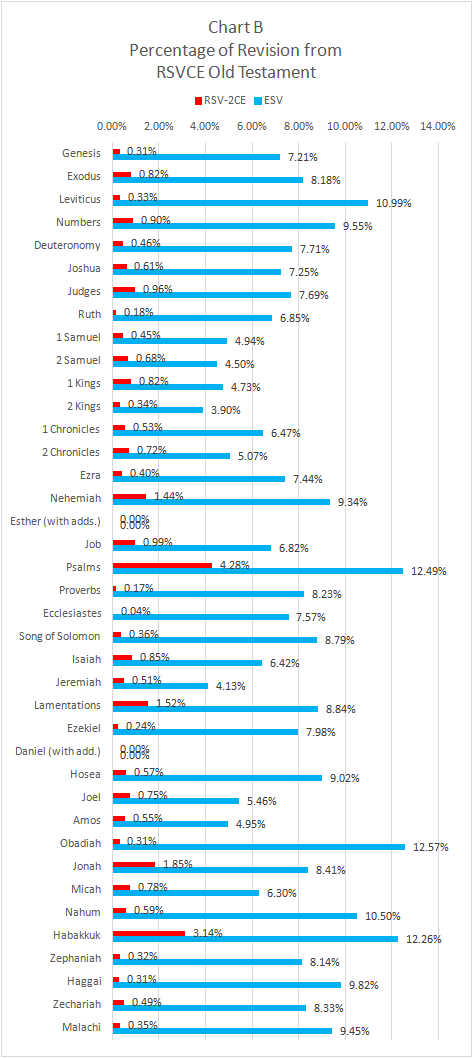

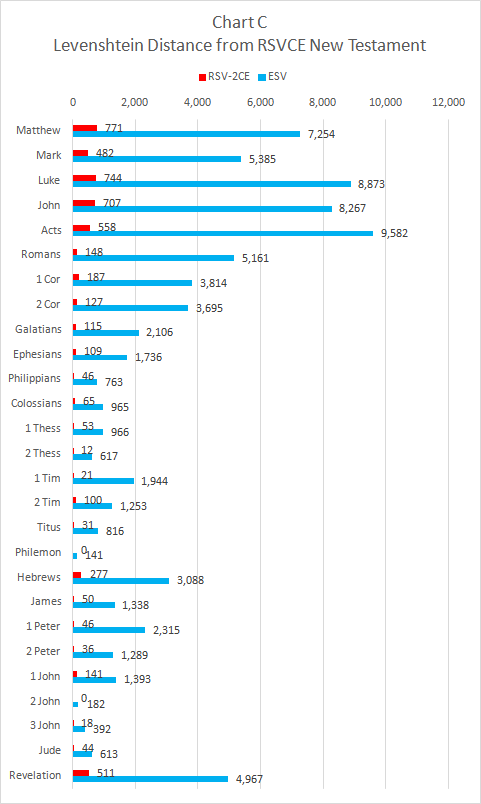

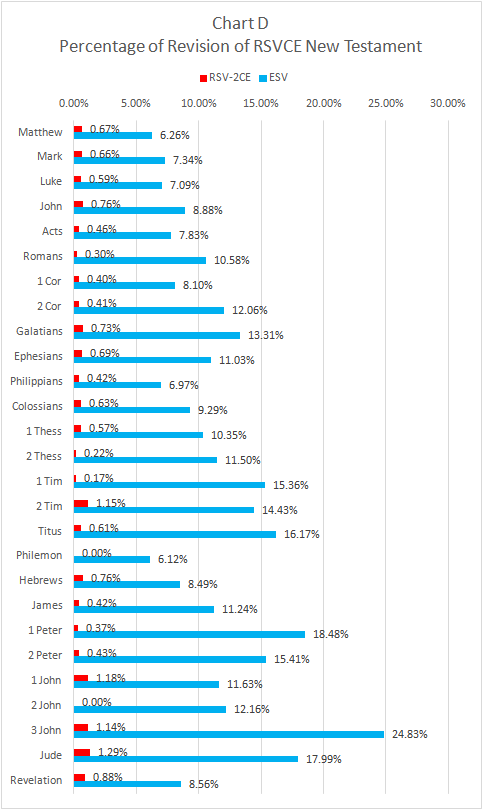

I’m including four charts comparing the RSV-2CE and the ESV:

- Chart A: Levenshtein Distance from RSVCE Old Testament

- Chart B: Percentage of Revision from RSVCE Old Testament

- Chart C: Levenshtein Distance from RSVCE New Testament

- Chart D: Percentage of Revision from RSVCE Old Testament

Observations

- In every book, ESV has substantially more revision than the RSV-2CE.

- RSV-2CE has the most revision in prayer-heavy texts (Psalms, Nehemiah, Habbakuk), where the RSV had lots of things like “thou hast” and “thou didst.” The RSV-2CE seems to focus on eliminating archaic vocabulary.

- In certain short books, the RSV-2CE has no revision (Philemon, 2 John).

- Ezekiel is a stand-out example of the contrast, where RSV-2CE changes only 467 characters, whereas ESV changes 15,380 (about 33 times more revision!).

- The ESV revises more in the NT (8.78%) than in the OT (7.33%), but the RSV-2CE revises more in the OT (0.88%) than in the NT (0.60%).

- The Book of Psalms has the most revisions in both, but that is expected since it is the longest book.

Overall, I hope that this post illustrates the value of the ESV-CE as a more substantial revision of the respected RSV-CE than its close cousin, the RSV-2CE.