A while back, I wrote a post on Hippolytus’ commentary on the Song of Songs, which is the first extant Christian commentary on the Song. Unfortunately, it has never been published in an English translation…until now. Yancy Smith wrote his dissertation on this topic and incorporated a translation of the commentary, including translations from the Georgian texts. Now, he has thoroughly revised and changed the dissertation into a book being published for 2013, but now available from Gorgias Press. So, if you are studying the Song of Songs or its interpretations and are in the market for ancient Christian commentaries, you can purchase the book, which is available now with a big discount from the Gorgias Press website. The book is entitled, The Mystery of Anointing: Hippolytus’ Commentary on the Song of Songs in Social and Critical Contexts.

Author Archives: catholicbiblestudent

Protestant Reformers on the Perpetual Virginity of Mary

So I was skimming an article by Gary Anderson on “Mary and the Old Testament” Pro Ecclesia 16 (2007): 33-55. and found a fascinating footnote:

Timothy George notes that Luther, Calvin, and Zwingli were all in agreement about the perpetual virginity of Mary even though Scripture makes no explicit judgment on this matter. “Strangely enough,” George observes, “Zwingli attempted to argue for this teaching on the basis of scripture alone, against the idea that it could only be held on the basis of the teaching authority of the church. His key proof text is Ezekiel 44:2: ‘This gate is to remain shut. It must not be opened: no one may enter through it. It is to remain shut because the Lord, the God of Israel, has entered through if” (“Blessed Virgin Mary,” 109). But this is hardly as strange as it appears. Zwingli is simply working from a typological identification that goes back to the patristic period.

Really?! The most protestant of Protestant reformers–in many ways the Big Three of Protestant reformers–all believed in Mary’s perpetual virginity. And they even use biblical evidence to back up their claims. Wow!

(Anderson refers to an article by Timothy George, “The Blessed Virgin Mary in Evangelical Perspective,” in Mary Mother of God, ed. Carl Braaten and Robert Jenson (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2004) 100-1.)

To me, this seemingly little point is actually huge for Protestant-Catholic dialogue, relations and for Protestants considering becoming Catholic. Often, the doctrine of Mary’s perpetual virginity is a sticking point since it is not explicitly mentioned in the Bible and it is one of the big four Catholic Marian dogmas. To realize that the original Protestant reformers embraced this doctrine could, I think, soften some of the tension between Catholics and Protestants on Marian issues.

Ancient Near Eastern Texts and the Bible

There are quite a few ancient Near Eastern texts that shed light on our understanding of the Bible, especially the Old Testament. The documents come from Egypt, Assyria, Babylon, Ugarit and other places. Their similarity in language, culture and historical context is immensely helpful in understanding the Old Testament more clearly. There have been two major publications of these texts in English translation to which scholars refer. The first collection, Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament, was edited by James Pritchard and published first in 1950, with a revised edition in 1955. For many years, the “ANET” was a standard reference for Old Testament scholars. However, in the 1990’s the ANET was replaced by a three volume work called The Context of Scripture, edited by William Hallo. This “COS” is now the standard scholarly presentation of ancient Near Eastern texts in translation. However, as you could imagine, the ANET and COS are not identical. They offer mostly the same texts, but COS omits some texts included in ANET and ANET omits many texts included in COS. And what if you find a reference to ANET, but need to locate it in COS? Lots of confusion could result from all of this! Fortunately, a certain Kevin P. Edgecomb, has provided a very helpful cross index of ANET and COS with notations as to which texts are included and excluded from the two publications. If you ever find yourself comparing texts from these two translations, his cross index will be indispensible to you.

How did Philadelphia get its name?

Ok, so this is really bizarre. Philadelphia is mentioned once in the Bible, in Revelation 3:7 where Jesus conveys a letter to the Christians there. So, I got curious, why was the city named “Philadelphia.” Of course, everyone knows that Philadelphia is the city of brotherly love. And the original Philadelphia was in Asia Minor, modern day Turkey–not Pennsylavania! So the original Philadelphia was founded by a king of Pergamon named Attalus II Philadelphus (or “philadelphos” in Greek). “Philadelphos” was this king’s nickname because he loved his brother so much.

Right, so how does that work? How is your love for your brother famous? Well, here’s how the story goes: Attalus II’s brother, Eumenes II, was the king of Pergamon. Once, when he was traveling back from Rome, his convoy came under attack and he was presumed dead. Word got back to Pergamon and so Attalus II ascended to the throne and married his brother’s wife, Stratonice. Well, a little while later, Eumenes shows up alive at Pergamon! Attalus II returns Stratonice to Eumenes and the two brothers reign together as co-regents. At a certain point during their co-regency, the Romans approach Attalus and try to get him to betray his brother for their benefit. Attalus refuses the offer and thus becomes renowned for his faithfulness to his brother. Finally, two years after Eumenes brief disappearance, he actually dies. Attalus II becomes sole monarch over Pergamon and re-marries Eumenes’ widow, Stratonice. How bizarre is that?! How often does a queen marry a king’s brother twice?

Anathema in the New Testament

Anathema shows up five times as a noun in the New Testament (Rom 9:3; 1 Cor 12:3, 16:22; Gal 1:8, 9) and oddly, one time as a verb (Acts 23:14). It is a strange, foreign-sounding word that has an oddly long life. For example, if you read the canons of the Council of Trent, each stated idea condemned by the Council is followed by “…anathema sit” or “let him be anathema [if he holds this view]. See the section on justification, for example. There’s even a joke about a Catholic monsignor who named his dog “Anathema,” so that he could yell at the dog, “Anathema sit!”

Often, the New Testament examples of “anathema” are translated as “accursed.” So, for example, in Gal 1:9 Paul teaches, “If anyone is preaching to you a gospel contrary to the one your received, let him be accursed” (ESV). The word there really is “anathema.”

The word does show up in the Septuagint 26 times (Lev 27:28 twice; Num 21:3; Deut 7:26 twice, 13:16, 13:18, 20:17; Josh 6:17, 6:18 thrice, 7:1 twice, 7:11, 7:12 twice, 7:13 twice, 22:20; Judg 1:17; 1 Chr 2:7; Judith 16:19; 2 Macc 2:13, 9:16; Zech 14:11). In these Old Testament references, “anathema” often refers to something “devoted” to the Lord (Lev 27:28; Josh 6:17), but it can refer to things that are cursed (Deut 7:26). Oddly, the word is used as a proper noun for a place name in Hebrew, “Hormah,” but in Greek, “Anathema” (Num 21:3; Judg 1:17). However, this is more a translation than a transliteration. The word “Hormah” is derived from the Hebrew verb hrm which means to devote something.

Ok, so what does anathema mean? Well, it comes from the Greek verb, anatithemi, which means to “lay upon” and therefore “refer, attribute, ascribe, entrust, commit, set up, set forth, declare.” The idea is that you might put an offering of some kind before a person or god, laying it upon an altar or perhaps at the feet of another.This verb actually shows up in Acts 25:14 and Gal 2:2, where a person “lays” a matter before another; in one case Festus lays Paul’s case before Felix, in the other, Paul lays his views before the apostles. So “anathema” means a “thing laid before” or a “thing devoted.” It translates the Hebrew word herem in the Old Testament, which as we saw above could refer to something devoted to God or something devoted “to destruction,” an abominable thing. So in light of the Septuagint, the New Testament uses of anathema follow in the second track, using “anathema” to mean “accursed” or “abominable.” The Liddell-Scott-Jones Lexicon does not offer a lot of help. Moulton-Miligan’s Vocabulary of the Greek New Testament (p. 33) expound on the Megara inscription mentioned by LSJ, which actually reads “anethema”, and they explain the spelling difference but translate the word as “curse!” The Thesaurus Linguae Graecae shows 1753 results for “anathema”, but most are post-New Testament. It seems to be a word that came into its own in the Septuagint and then used in the NT with it’s “septuagintal” sense of “accursed.”

MOOC’s for Bible Students?

Recently, I’ve learned a little bit about MOOC’s (Massively Open Online Courses). A MOOC is usually a course taught for credit at a university that is then opened to the public for free. The first serious MOOC was offered by Stanford’s Sebastian Thrun in Fall 2011 with 150,000 students. The New York Times just did an article about MOOC’s which lays out the basics of the history and theory. The big MOOC companies are Udacity, edX, Coursera, and Khan Academy. Theses organizations put on courses of their own or help universities bring MOOC’s to market. For most schools, MOOC’s are really just an advertising ploy. If you get 100,000 people involved in a course that’s a pretty big deal and maybe you’ll get some paying customers (er…students) out of it.

Now my specific interest is whether MOOC’s could be used to teach the Bible or biblical things. MOOC’s tend to lend themselves to very technical subjects like math, physics, computer programming, etc. In technical subjects, interactive learning assessments can be designed to check whether students are really learning since there is almost always a right answer and a wrong answer. But when it comes to the humanities (literature, history, art, religion, politics, etc.), knowledge is usually more “fuzzy,” for lack of a better term. Knowledge of successful political movements, of literary techniques, of what artist used what kind of paint, of theological concepts, does not have the same kind of hard edges that knowledge of formulas, equations, and computer code do. And with religion in particular, personal or organizational views/opinions/beliefs are often embedded in teaching and writing content so much that they cannot be separated from cold, hard, facts.

On the one hand, it seems to me that as the Internet and online education develop, theology and biblical studies will have to catch up. Theological educators of all kinds–from weekend warrior catechists to doctoral level professors–will have to change the way they approach education. It seems to me that the Internet is “democratizing” information at a very quick pace and that information is becoming more systematized by a crowd-sourced world. I think that has huge implications for religion. It used to be that if you studied at a seminary of a particular denomination, you only had access to the books in your seminary library and the denomination could choose to avoid putting certain books or journals in it, restricting the flow of information. But now, you can have access to whatever information you want anytime you want and no librarians can control who gets access to what. I think this kind of freedom is already re-shaping the religious landscape. When people have religious questions, they don’t go ask their pastor, they ask Google first. So to me, it seems that religious information will become organized, systematized and democratized in such a way that educators will need to re-think the way they educate.

On the other hand, I wonder if all this information-democratization process is good for religious education. I mean, can you really compress the Sermon on the Mount into a multiple choice question? There is something about theological education that is intangible, or perhaps, spiritual. It involves deeper movements of the mind and soul than solving equations or addressing technical matters. I think I could describe religious learning as involving the intuition–the indirect circuits of the brain–more so than deduction. Technical education, whether engineering or computer science, often deals with technical “problems” that need technical “solutions.” A great deal of the learning and the actual work of these fields deals with life on a problem-solution continuum. The role of the technician is to help clients get from one to the other. But in theology, philosophy, political science, etc., the role of the student and thinker is much different. The thinker must address the whole all at once, contemplating more wide-ranging questions of how everything fits together, what life really is all about and what my role in the universe is. Sometimes it seems that these kinds of issues cannot be crammed into a multiple choice question or a threaded online discussion, but require engagement with reality (say, through prayer or service), meditation (long, serious thinking), and conversation, in which those thinking about the same questions talk about how to understand the reality at hand and what to personally do about it. (E.g., if Jesus commands his followers to “go and make disciples,” how and in what way does that apply to me today? What should I do about it?) Can the type of intellectual movements required for true theological engagement happen in a MOOC?

Now, I know that at least one quasi-theological MOOC has been attempted. The Catholic Distance Learning Network is doing two MOOC’s. One is on “Online Teaching and Learning.” The other is called “Teaching Research Design.” The project is being led by Sebastian Mahfood of Holy Apostles College and the CDLN worked with Edvance360 to set up the courses. There’s an article about it here. The effort is interesting and I hope they report to the public the results of the project. I’m especially interested in their enrollment numbers. I can’t imagine they’ll get 100,000 students! However, the courses are not truly theological. Both of them seem rather technical in nature–not as much as computer programming–but technical in terms of education and research strategies. I’d really like to see someone offer a MOOC on “Christology” or “Biblical Hermeneutics” or something much more difficult to assess.

The areas in theological and biblical studies that would lend themselves to a MOOC most easily are those that are most technical. I think, for example, that biblical language study would be the first place for MOOC’s to go for theology. But I wonder if other technical subjects like Thomistic philosophy or bio-ethics or even comparative religions might be able to be taught through a MOOC. The other thing is that MOOC’s might just be a fad, but there’s so much momentum behind them right now that I think they’ll be with us to stay at least in some format. I’m interested to see what theologians and Bible scholars come up with when it comes time to make a MOOC. I hope that someone will figure out how to use the new format to teach a new generation of religious thinkers. So if you hear of any theology or biblical studies MOOC’s going on, post a comment here to let me know.

Scripture and the Synod on the New Evangelization

I was pleased that the final propositions of the recently concluded Synod on the New Evangelization included something about Scripture. The first mention is in Proposition 9 where the Synod fathers recommend the composition of an instructional book for training evangelists. They propose that this book contain, “Systematic teaching on the kerygma in Scripture and Tradition of the Catholic Church.” The “kerygma” is a favorite word of the synod and it refers to the core message of the Gospel, the essential truth about the life of Jesus that ought to be proclaimed whenever the Gospel is proclaimed.

The synod’s Proposition 11 is all about Scripture:

Proposition 11 : NEW EVANGELIZATION AND THE PRAYERFUL READING OF SACRED SCRIPTURE

God has communicated himself to us in his Word made flesh. This divine Word, heard and celebrated in the Liturgy of the Church, particularly in the Eucharist, strengthens interiorly the faithful and renders them capable of authentic evangelical witness in daily life. The Synod Fathers desire that the divine word “be ever more fully at the heart of every ecclesial activity” (Verbum Domini, 1).

The gate to Sacred Scripture should be open to all believers. In the context of the New Evangelization every opportunity for the study of Sacred Scripture should be made available. The Scripture should permeate homilies, catechesis and every effort to pass on the faith.

In consideration of the necessity of familiarity with the Word of God for the New Evangelization and for the spiritual growth of the faithful, the Synod encourages dioceses, parishes, small Christian communities to continue serious study of the Bible and Lectio Divina, the — the prayerful reading of the Scriptures (cf. Dei Verbum, 21-22).

These guidelines from the synod fathers are not necessarily surprising. Rather, they re-emphasize themes from recent magisterial documents on the Bible, explicitly citing Dei Verbum (of Vatican II fame) and Verbum Domini (the most recent post-synodal apostolic exhortation penned by Benedict XVI). The proposition highlights the connection between the “Word made flesh” and the Bible itself, emphasizing their identity and difference. The “divine Word” is the Scripture, yes, more so it is Jesus himself. In the context of the New Evangelization, the synod teaches here that Scripture strengthens the faithful and is an essential component in spiritual growth. Also, they emphasize the centrality of Scripture to the teaching and preaching that goes on in the life of the Church. And, just as if they were intending to warm a CatholicBibleStudent’s heart, they insist twice that study, and even serious study of Sacred Scripture should be part and parcel of what the Church does in her daily life and in promotion of the New Evangelization. The mention of “small Christian communities” is interesting. The phrase shows up here and in Proposition 42. I think it refers to any kind of small group that meets within a parish or movement, but I wonder if it is inspired by the kinds of ideas in a book by Stephen Clark called Building Christian Communities. There’s a bit more about Catholic Small Chrisitian Communities on CatholicCulture.org. Lastly, the synod fathers recommend the prayerful reading of Scripture, Lectio Divina. Lectio Divina has been a consistent theme over the past few years in magisterial documents, most notably in in Verbum Domini. I hope that Catholics are able to take it to heart. I think though that since there is not an agreed upon structure for it apart from monastic traditions that it will be hard for most lay Catholics to practice. Some clear instructions on how to do it would be helpful. All in all, I’m happy the synod took time to talk about Scripture in its final propositions. We’ll see how much of this makes it into Benedict’s next post-synodal apostolic exhortation.

Gilbert of Hoyland on Prayer

“Reading should serve prayer, should dispose the affections, should neither devour the hours nor gobble up the moments of prayer. When you read you are taught about Christ, but when you pray you join him in familiar colloquy. How much more enchanting is the grace of speaking with him than about him!”

-Gilbert of Hoyland

John Paul II on the Mission of Bible Scholars

John Paul II gave an address to the Pontifical Biblical Commission upon receipt of their document, the Interpretation of the Bible in the Church. In that speech, he outlined a few points regarding the mission of biblical scholars that I found helpful and motivating. Unfotunately, it’s not in English on the Vatican website, but it is in French. There’s an English translation of some excerpts here. Here are a couple quotes:

“To this end, it is obviously necessary that the exegete himself perceive the divine Word in the texts. He can do this only if his intellectual work is sustained by a vigorous spiritual life.” (sec. 9)

“In order better to carry out this very important ecclesial task [the explanation of Scripture], exegetes will be keen to remain close to the preaching of God’s word, both by devoting part of their time to this ministry and by maintaining close relations with those who exercise it and helping them with publications of pastoral exegesis.” (sec. 11)

-John Paul II, “Address on the Interpretation of the Bible in the Church,” In The Scripture Documents: An Anthology of Official Catholic Teachings (trans Dean P. Bechard; Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 2002) 175, 177.

In the first quote, John Paul highlights the importance of arriving at the meaning of the text intended by God, the so-called “divine meaning” or the “theological meaning” (a phrase often used by Fr. Frank Matera in describing the exegete’s aim). To me, this concept is very helpful in understanding what biblical exegesis is all about. It really does have a goal that is realizable. Sometimes it seems in the face of the immense stacks of exegetical books in theological libraries that no one will ever figure out the meaning of the Bible! I mean, if people have been seriously working on it for 2,000 years and still feel the need to publish more and more books about it, where’s the hope for a resolution? But the Bible does have meaning, one that can be discovered and related and believed in. John Paul also frames the task of exegesis well as a matter of “perception,” and a kind of perception that is informed by prayer, spiritual life. So the exegete could never be replaced by a robot. Rather, his personal spiritual life is somehow involved in the act of perception of the divine meaning of the biblical text.

In the second quotation above, John Paul highlights the pastoral dimension of the exegetical task. Exegetes, he says, either ought to be preachers themselves or to help preachers in their exposition of God’s word. Lots of Bible scholars, I think, do not see themselves this way at all. But here John Paul insists that biblical scholars ought to be engaged in publishing pastoral exegesis–i.e. popular works–not just scholarly works. He adds after the sentence I quoted above, “Thus they will avoid becoming lost in the complexities of abstract scientific research, which distances them from the true meaning of the Scriptures. Indeed, this meaning is inseperable from their goal, which is to put believers into a personal relationship with God.” (sec. 11, p. 177). So, in John Paul’s mind, there is a distinct possibility of BIble scholars becoming lost! That would not be good. However, I wonder if John Paul had some biblical scholars in mind that he had met in his lifetime–ones who were obsessed with weird little details of Hebrew poetry or archaeology and unable to inspire anyone’s faith. That would be a bad place to be, a lost, uninspiring Bible scholar, trapped in the ivory tower and unable to communicate what he knows to regular people who want to be in a personal relationship with God. I’ll have to think about this one for a while.

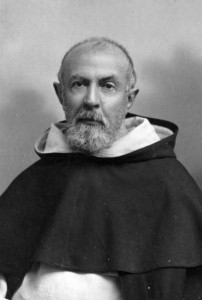

Lagrange on Catholic Bible Interpretation

Marie-Joseph Lagrange, one of the founders of the Ecole Biblique, was one of the most important Catholic BIble scholars at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries. Today, I came across a lecture he gave on what Catholic biblical exegesis is all about. It’s interesting from a historical perspective since it is before Vatican II and before Divino Afflante Spiritu. Here’s a little excerpt for some flavor:

Marie-Joseph Lagrange, one of the founders of the Ecole Biblique, was one of the most important Catholic BIble scholars at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries. Today, I came across a lecture he gave on what Catholic biblical exegesis is all about. It’s interesting from a historical perspective since it is before Vatican II and before Divino Afflante Spiritu. Here’s a little excerpt for some flavor:

H, then, Scripture had been the only

means to assure the preservation of a doctrine

which is much richer than the ” weak and needy

elements ” of the old Law, God would have

provided very poorly for its preservation. The

answer of tradition is more complete and more

precise. The New Testament contains neither

a creed nor a sacramentary. And doctrine is

preserved in the Church as an ever living and

acting faith.Precisely ! it will be said. This faith lives,

consequently it evolves, hke all human things.

With time it will give to the questions put before

it answers more complete and more precise.Granted, but this development is not a deformation.

The Church, in virtue of a supernatural

logic, which is at the same time perfectly rational,regards the truth, which she has received from

God Himself, as having an immutable character,

and she is intent on transmitting it just as she

received it in its substantial elements.

But do not forget that we are deahng here with

this question of the development of doctrine only

from the viewpoint of the exegete. The difficulty

that is urged regards only the sincerity of interpretation.

It may be thought that the exegesis of the

Church, being imposed upon her by her dogma,

will lack sincerity since it will lack hberty. The

objection does not apply to Cathohc exegesis.

The danger it calls attention to may exist only for

a society which has no other rule of faith than

the Bible, and is bound to find therein all the

truths which it professes. But such is not the

case with the Church. Why should she torture

texts to get from them what she can get from

tradition? A Cathohc may and must beheve in

dogma not enunciated in Scripture, as, for instance,

in the perpetual virginity of Mary. He

is not, then, obhged to have recourse to any

violent form of exegesis. The texts remain undisturbed. (pp. 38-39)

You can get the whole text of his lecture on “The Exegesis of the Catholic Church” in a 1920 translation in a book called “The Meaning of Christianity” on archive.org. Happy reading!