One of the famous phrases of the Second Vatican Council that has always stuck in my mind is from Dei Verbum, which teaches that “Holy Scripture must be read and interpreted in the sacred spirit in which it was written” (section 12). That is the translation from the Vatican website. The Latin reads, “Sacra Scriptura eodem Spiritu quo scripta est etiam legenda et interpretanda sit.” Notably, the phrase “eodem Spiritu” means “same Spirit” not “sacred Spirit.” The old Walter Abbot translation gets this right and so does the Catechism (section 111). But the point is, where does this principle come from?

Well, if you take a look at the footnote to the line, you’ll see this:

EDIT 1/6/2014 (deleted text struck out and added text maroon):

9. cf. Pius XII, encyclical “Humani Generis,” Aug. 12, 1950: A.A.S. 42 (1950) pp. 568-69: Denzinger 2314 (3886).9. cf. Benedict XV, encyclical “Spiritus Paraclitus” Sept. 15, 1920:EB 469. St. Jerome, “In Galatians’ 5, 19-20: PL 26, 417 A.

Great, so we have to go back and look at Humani Generis for this idea. The Denzinger reference 3886 equates to the 21st paragraph of the encyclical which talks about the value of biblical exegesis, that it renews theological inquiry, giving it a constant freshness. The paragraph does refer to Pius IX’s letter Inter gravissimas from 1870, but the funny thing is that the phrase about the “same Spirit in which it was written” does not appear anywhere in the encyclical.

I made a mistake in this original post by associating a footnote belonging to Article 11 to Article 12, as was pointed out to me by a friendly reader. The correct footnote points to Benedict XV and St. Jerome. The relevant text from Benedict XV’s encyclical is this:

35. But in a brief space Jerome became so enamored of the “folly of the Cross” that he himself serves as a proof of the extent to which a humble and devout frame of mind is conducive to the understanding of Holy Scripture. He realized that “in expounding Scripture we need God’s Holy Spirit”;[55] he saw that one cannot otherwise read or understand it “than the Holy Spirit by Whom it was written demands.”[56] Consequently, he was ever humbly praying for God’s assistance and for the light of the Holy Spirit, and asking his friends to do the same for him. We find him commending to the Divine assistance and to his brethren’s prayers his Commentaries on various books as he began them, and then rendering God due thanks when completed.

I have bolded the most important text, which is really a couple citations from St. Jerome. The two references are: “55. Id., In Mich., 1:10-15” and “56. Id., In Gal., 5:19-21.” The drafters of Dei Verbum point us to the second citation, from Jerome’s commentary on Galatians, the phrase there reads in Latin, “Quicumque igitur aliter Scripturam intelligit, quam sensus Spiritus sancti flagitat, quo conscripta est…” (Source: p. 417)This can be rendered in English, “Whoever, therefore, understands Scripture in any other way than the sense of the Holy Spirit by whom they were written…” This phrase seems to be underlying Dei Verbum‘s statement, but the wording is actually closer in yet another text.

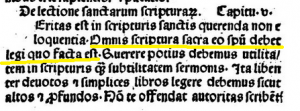

So, here’s where Thomas a Kempis comes in. In his famous book, The Imitation of Christ, he talks about reading Scripture in Book I, chapter 5 and says that “it should be read in the same spirit with which it was made” (Harold Gardiner translation, 1955). So, is Vatican II quoting Thomas a Kempis without attribution? It’s hard to say. You can read the original Latin text online from this 1486 publication of the Imitation of Christ. Here’s an image for you:

For those of you without a magnifying glass, the underlined text reads “Omnis Scriptura Sacra eo Spu debet legi quo facta est.” (“Spu” here is an abbreviated form of “Spiritu.”) My translation is then: “All of Sacred Scripture ought to be read in the same Spirit in which it was made.” However, a translation from 1938 that was republished in 1959 reads quite freely, “Each part of the Scripture is to be read in the same spirit in which it was written.” I’m not suggesting that the Council Fathers were reading this translation and then formulating their Latin text, but that Thomas a Kempis was on their minds when penning this line. I would be interested to see if there is further evidence for this in some of the background documents of the Council. I just stumbled across it, and thought you would like it if I’d share it with you.

For those of you without a magnifying glass, the underlined text reads “Omnis Scriptura Sacra eo Spu debet legi quo facta est.” (“Spu” here is an abbreviated form of “Spiritu.”) My translation is then: “All of Sacred Scripture ought to be read in the same Spirit in which it was made.” However, a translation from 1938 that was republished in 1959 reads quite freely, “Each part of the Scripture is to be read in the same spirit in which it was written.” I’m not suggesting that the Council Fathers were reading this translation and then formulating their Latin text, but that Thomas a Kempis was on their minds when penning this line. I would be interested to see if there is further evidence for this in some of the background documents of the Council. I just stumbled across it, and thought you would like it if I’d share it with you.

You might be surprised when you’re reading the New Testament and a verse disappears into thin air. For example, if you are reading Acts 8:36, you would expect Acts 8:37 to follow, but oddly, 8:38 is the next verse. What happened to Acts 8:37?

You might be surprised when you’re reading the New Testament and a verse disappears into thin air. For example, if you are reading Acts 8:36, you would expect Acts 8:37 to follow, but oddly, 8:38 is the next verse. What happened to Acts 8:37?