Last Thursday, I was interviewed on Ken Huck’s show on Radio Maria, “Meet the Author,” about my book Light on the Dark Passages of Scripture. Take a listen:

Here’s a link to the interview: http://radiomaria.us/january-28-2016-dr-mark-giszczak/

Last Thursday, I was interviewed on Ken Huck’s show on Radio Maria, “Meet the Author,” about my book Light on the Dark Passages of Scripture. Take a listen:

Here’s a link to the interview: http://radiomaria.us/january-28-2016-dr-mark-giszczak/

On Monday, I hosted a webinar about my new book: Light on the Dark Passages of Scripture. It was an hour long session that included some Q&A. If you want to take a look, here’s the link:

https://attendee.gotowebinar.com/recording/8486854649388533761

A few years ago, the media reported about Joan Ginther, the woman who has won the lottery jackpot four times. Yes, four times! She’s won all told, about 20 million dollars. The Harper’s story about her by Nathaniel Rich probed the probability of her luck and found that it was about one in 18 septillion. There are other reasons why she might be so “lucky” like her Ph.D. in statistics. But what caught my eye from Rich’s story was this line:

There are one septillion stars in the universe, and one septillion grains of sand on Earth.

If that doesn’t make a Bible scholars antennae go up, I don’t know what will! This should remind any Bible student of this line in Genesis:

I will indeed bless you, and I will multiply your descendants as the stars of heaven and as the sand which is on the seashore. (Gen 22:17 RSV)

God tells Abraham that he will have as many descendants as there are are stars and as there are grains of sand. What is so amazing about this is that upon scientific observation, those two totals are the same! There are roughly the same number of grains of sand on Earth as there are stars in the universe. Of course, there are many different estimates for these things. NPR even did a story on these questions. And then you start thinking, wow, we have a ways to go if Abraham is going to have a septillion descendants! If there have been, at highest estimates, 125 billion people ever, then we’re only 6.94 quadrillionths of the way there! (If I did my math right.) Whether you find interesting the number of Abraham’s descendants equaling the number of grains of sand or the number of grains equaling the number of stars, at least you can be happy knowing that the probability of winning the lottery four times divided by the number of Abraham’s promised descendants is 18.

Next Monday, I will be hosting a live webinar about my new book, “Light on the Dark Passages of Scripture” with the help of my publisher, Our Sunday Visitor:

New FREE webinar: “Light on the Dark Passages of Scripture” w/ author, Dr. Mark Giszczak. More info & sign up: https://t.co/afxcNrDO04

— Our Sunday Visitor (@OSV) January 11, 2016

Recently, I made a few appearances on radio:

-On Friday, January 8, I was on the Busted Halo Show with Fr. Dave Dwyer on SiriusXM, chan. 129.

-On January 6, I was on Andrew Whaley’s daily show, The Counter Position:

-Last night, I was on Fr. Ron Lengwin’s show, Amplify, on KDKA in Pittsburgh

Several years ago in 2007, I put together a bibliography of commentaries on Baruch on this blog. A handful of new work has appeared since then that it is worth listing here. Unfortunately, there is still a dearth of publication on the deuterocanonical book of Baruch, but it is worth cobbling together what has been done. Hopefully, more will be written! The book of Baruch as normally presented in a Catholic Bible includes the Epistle of Jeremiah as the sixth chapter.

New Commentaries on Baruch

Adams, Sean A. Baruch and the Epistle of Jeremiah: A Commentary Based on the Texts in Codex Vaticanus. Septuagint Commentary. Brill, 2014. (Although I haven’t seen it yet, this looks like the most promising, most comprehensive recent work. It claims to be the first English language commentary.)

Hill, Robert Charles, trans. Theodoret of Cyrus: Commentaries on the Prophets. Vol. I. Holy Cross Orthodox Press, 2007. (This includes commentaries on Jeremiah, Baruch and Lamentations.)

Viviano, Pauline. Jeremiah, Baruch. New Collegeville Bible Commentary, vol. 14. Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 2013. (This book includes about 20 pages on Baruch: a 2-page introduction and then the text of Baruch with commentary.)

Wacker, Marie-Theres. Baruch and the Letter of Jeremiah. Wisdom Commentary. Michael Glazier, 2016.

Thanks to a student of mine, I just noticed something I never had before. Let’s take it step-by-step. First, there’s the rather odd self-deprecatory statement in Psalm:

If I forget you, O Jerusalem, let my right hand wither! (Psa 137:5 RSV)

It is the mournful sentiment of the exile, away from the Land, looking back on Jerusalem, hoping for the day of return. The day of return is delayed again and again. Even when the people do return from exile, there is a sense that have not really returned. They long for a new exodus to really bring them back. So, when Jesus shows up and starts performing miracles, one of the very first miracles he performs is to restore a man’s withered hand:

Again he entered the synagogue, and a man was there with a withered hand. 2 And they watched Jesus, to see whether he would heal him on the Sabbath, so that they might accuse him. 3 And he said to the man with the withered hand, “Come here.” 4 And he said to them, “Is it lawful on the Sabbath to do good or to do harm, to save life or to kill?” But they were silent. 5 And he looked around at them with anger, grieved at their hardness of heart, and said to the man, “Stretch out your hand.” He stretched it out, and his hand was restored. 6 The Pharisees went out and immediately held counsel with the Herodians against him, how to destroy him. (Mark 3:1 ESV)

Maybe what we’re looking at here is that the man with the withered hand represents the whole people who truly have “forgotten Jerusalem.” They have not recognized the “time of their visitation” (see Luke 19:44). By restoring the man’s withered hand, Jesus shows how he will completely heal the people. Though they have forgotten him and the place of his dwelling (the Temple), God has not forgotten them, but will bring them to restoration. The man’s withered hand represents the fact that the self-deprecatory oaths that the exiles took have come home to haunt them. They have actually received the due punishment, but God will reach out to heal them and bring them back. Jesus will lead them on a new exodus and their self-cursed bodies will receive healing.

Yesterday, I was on the Catholic Answers Live! show talking about my new book. Callers asked some tough questions about weird biblical passages–Abraham sacrifices Isaac, Jephthah sacrifices his daughter, innocent suffering, etc. You can listen to a recording of the hour here:

http://www.catholic.com/sites/default/files/audio/radioshows/ca151118b.mp3

Yesterday, I got interviewed about my new book, Light on the Dark Passages of Scripture, by my friend Andrew Whaley on his daily show, The Counter Position. You can take a listen right here:

This morning I was interviewed on the Son Rise Morning Show about my new book, Light on the Dark Passages of Scripture. You can take a listen here: (My interview starts at about 2:12:30)

11-16-2015

Podcast Episode

Categories

Filetype: MP3 – Size: 82.24MB – Duration: 2:59:40 m (64 kbps 22050 Hz)

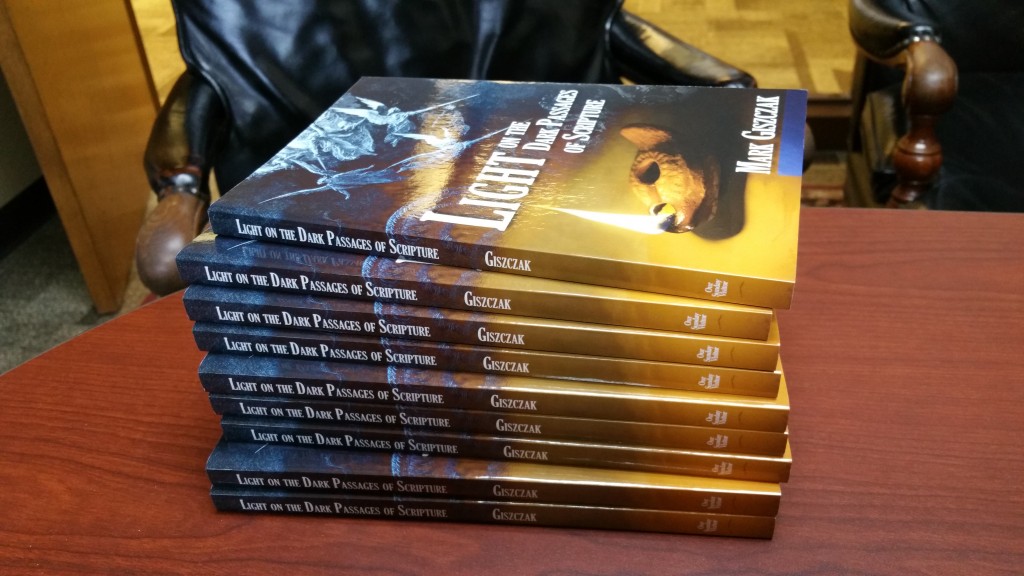

If you’ve been following along here, you’ll have noticed that I’ve been talking a lot about the book I just wrote. Finally, last night, I got physical copies of the book in my hands. It’s called “Light on the Dark Passages of Scripture.” Take a look: So…if you want to order one and see what I have to say about the nasty stuff in the Bible, you can order in two ways:

So…if you want to order one and see what I have to say about the nasty stuff in the Bible, you can order in two ways:

Here at OSV: https://www.osv.com/Shop/Product?ProductCode=T1609

And here at Amazon: http://www.amazon.com/Light-Dark-Passages-Scripture-Giszczak/dp/1612788033

In the book, I deal with a lot of the passages that give Bible readers grief: the killing of the Canaanites, child sacrifice, innocent suffering, the problem of Hell. I sort through these problems in a detailed, yet accessible way and try to get the bottom of how it is the God of the Old Testament and the God of the New Testament could be the same. I hope you enjoy the book!