I was recently interviewed by T.L. Putnam on his podcast entitled “Outside the Walls.” It always makes me think of the great basilica of St. Paul Outside the Walls in Rome. I have been on his show before, but this time we’re talking about my new commentary on the Wisdom of Solomon in the CCSS series. Check it out:

Category Archives: Random

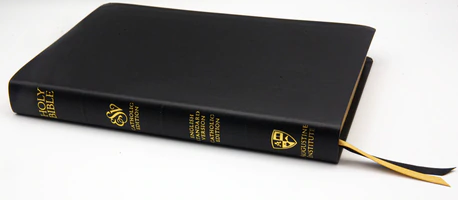

Wisdom of Solomon Book Release Day!

Hooray! My commentary on the Wisdom of Solomon in the Catholic Commentary on Sacred Scripture is now released as of today, February 13, 2024.

Description of the Book

The Wisdom of Solomon is the first volume published in the Catholic Commentary on Sacred Scripture, Old Testament series. The commentary offers a robust introduction to the historical and theological background of the often-overlooked Wisdom of Solomon, the RSV-2CE translation of the biblical text, cross references, Catechism and Lectionary references, and a detailed interpretation of each passage in the 19-chapter book. It also includes helpful sidebars on biblical background and important references in the living tradition of the Church. This commentary guides the Catholic reader in a thorough and careful study of the Wisdom of Solomon.

I hope you all pick up a copy, read it, enjoy it and learn something from it!

Where to Find the Book

- Baker: https://bakeracademic.com/p/Wisdom-of-Solomon-Mark-Giszczak/542807

- Amazon: https://a.co/d/5ufZiPn

- Soon, Verbum software: https://verbum.com/product/252803/wisdom-of-solomon

Bellybutton Statues

Image credit: Fallaner, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

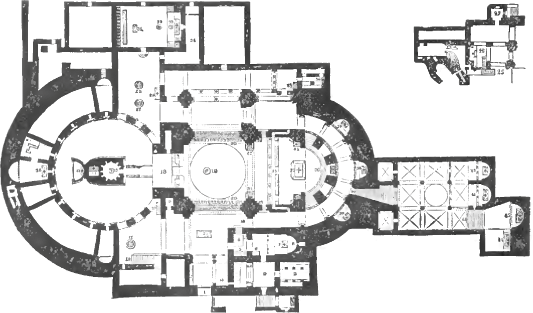

One of the weirdest things that I learned in college is that during the time of St. Cyril of Alexandria, there was a bellybutton statue in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. I saw a circle on a diagram of the church that was labeled “omphalos.” That is the Greek word for bellybutton. I asked my professor what it was about and, if I recall correctly, he explained that it meant that Christians regarded the Church of the Holy Sepulchre as the center of the world. I’ve added a similar diagram here of the modern church and you can see a tiny “19” at the middle. Yes, to this day, the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem has a bellybutton statue at the very center! I’ve also posted a picture of it so you can see what it looks like.

Image from: M’Clintock, John, and James Strong. “Sepulchre of Christ.” Cyclopædia of Biblical, Theological, and Ecclesiastical Literature. New York: Harper & Brothers, Publishers, 1880.

Image from: M’Clintock, John, and James Strong. “Sepulchre of Christ.” Cyclopædia of Biblical, Theological, and Ecclesiastical Literature. New York: Harper & Brothers, Publishers, 1880.

So where did this idea come from? Were there other bellybutton statues in the ancient world? It turns out, there were quite a few.

The Omphalos of Delphi

Image credit: Yucatan (Юкатан), CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

The most famous bellybutton statue was at Delphi where the famous Greek Oracle of Delphi would receive visitors and offer her cryptic prophecies. Some archaeologists think she was inhaling intoxicant vapors from the geothermal features at the site, which helped her achieve an altered state of consciousness for the purpose of prophesying. Some even believe that she breathed these fumes through the omphalos statue itself. Very strange! You can actually still pay a visit to Delphi and find the belly button statue from antiquity in their museum.

Image credit: Berthold Werner, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Outdoors at Delphi, you will also find another bellybutton statue that looks more plain—like a cone of plain rock with no decoration.

The Bellybutton of Rome

Ancient Rome had something similar, called the umbilicus Urbis Romae, the belly button of the City of Rome. It was a statue or monument of a belly button that officially marked the center of the city. It was the point from which all distances were measured. Today it looks a little like a beat up pile of bricks with a doorway:

Image credit: Karlheinz Meyer, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

The Center of the World

The point of all of these belly button statues is that they mark a spot regarded as the “center of the world.” We find this idea in the Bible at the Book of Ezekiel, where the prophet is told,

“Thus says the Lord GOD: This is Jerusalem; I have set her in the center of the nations, with countries round about her.” (Ezek 5:5 RSV2CE)

In fact, many religious traditions identify a certain place as the center to which everything relates. Consider these examples outlined by Zimmerli, Cross and Baltzer:

The wealth of material gathered by Wensinck and Roscher (see also Holma) makes it additionally clear that not only the assertion of living in the center of the world, but also the specific reference to the “navel” (ὄμφαλος) is attested in a wide surrounding area. In Greece, alongside the dominating claim of Delphi, there stands the conception (apparent only in monuments rather than in literature) of the Eleusinian mystery cults that Athens, the μητρόπολις τῶν καρπῶν, was the place of the ὄμφαλος. In the wider Greek world the same claim is made by Paphos, Branchidai, Delos, Epidauros. In post-biblical tradition it gained significance through its connection with the Adam legend in its relationship to Golgotha, Zion and Moriah and perhaps also with Hebron. Islam, for its part, has transferred the tradition to Mecca. (Walther Zimmerli, Frank Moore Cross, and Klaus Baltzer, Ezekiel: A Commentary on the Book of the Prophet Ezekiel, Hermeneia [Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1983], 311.)

So many places have claimed to be the “omphalos,” the belly button or navel of the world. And some of these places mark their claim with a statue of a belly button. The ones we have noticed here include:

- Delphi

- The Church of the Holy Sepulchre

- The Roman Forum

St. Teresa and Life as an “Inconvenient Hotel”

You might have read this quotation at some point:

In light of heaven, the worst suffering on earth, a life full of the most atrocious tortures on earth, will be seen to be no more serious than one night in an inconvenient hotel.

This quote is often attributed to Mother Teresa, but elsewhere it is attributed to St. Teresa of Avila. I looked high and low for a source. I found my way to p. 47 in Lee Strobel’s book, The Case for Faith. But there, the quote is actually in the mouth of the famous Catholic author, Peter Kreeft citing “St. Teresa.” Kreeft himself alludes to the quotation on p. 139 in his book, Making Sense Out of Suffering, but he does not actually quote it. So where does that leave us?

An Alternate Version

I found an alternate version of the quotation that goes like this:

From heaven even the most miserable life will look like one bad night at an inconvenient hotel.

That one is attributed to St. Teresa of Avila, but these two quotes must have a common lineage, right?

Finding the Source of the Quotation

I think I finally tracked the thread of the quote down to chapter 40 of The Way of Perfection by St. Teresa of Avila, where she is comparing life in hell to life on earth as two alternate hotels. I will quote the larger context here:

What will become of the poor soul that, after being freed from the sufferings and trials of death, falls immediately into these hands? What terrible rest it receives! How mangled as it goes to hell! What a multitude of different kinds of serpents! What a terrifying place! What a wretched inn! If it is hard for a self-indulgent person (for such are the ones who will be more likely to go there) to spend one night in a bad inn, what do you think that sad soul will feel at being in this kind of inn forever, without end?

Let us not desire delights, daughters; we are well-off here; the bad inn lasts for only a night. Let us praise God; let us force ourselves to do penance in this life. How sweet will be the death of one who has done penance for all his sins, of one who won’t have to go to purgatory! Even from here below you can begin to enjoy glory! You will find no fear within yourself but complete peace.

(Source: Teresa of Ávila, The Way of Perfection, Meditations on the Song of Songs, and The Interior Castle, trans. Kieran Kavanaugh and Otilio Rodriguez, vol. 2 of The Collected Works of St. Teresa of Avila [Washington, D.C.: ICS Publications, 2017], 195.)

So there it is, I think. Life on earth is like a bad night at a bad inn. Mother Teresa loved St. Teresa of Avila, so it is very possible that she recycled the quotation and expanded it, but I have not found any evidence of it in print yet. If you do, let me know in the comments. If I do, I guess I’ll have to post a follow-up.

What is the Sword of Damocles?

For some reason, I keep hearing the phrase “the sword of Damocles” over and over. I’m not sure if everyone in the world decided to brush off their Latin and read some classics during the Covid quarantine or what. But somehow, this particular classical reference is back in vogue and you’ve probably heard it too. So what is this famous sword?

Who is “Damocles” Anyway?

Here’s a short entry on him from The Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology (1870):

DAMOCLES (Δαμοκλῆς), a Syracusan, one of the companions and flatterers of the elder Dionysius, of whom a well-known anecdote is related by Cicero. Damocles having extolled the great felicity of Dionysius on account of his wealth and power, the tyrant invited him to try what his happiness really was, and placed him at a magnificent banquet, surrounded by every kind of luxury and enjoyment, in the midst of which Damocles saw a naked sword suspended over his head by a single horse-hair—a sight which quickly dispelled all his visions of happiness. (Cic. Tusc. v. 21.) The same story is also alluded to by Horace. (Carm. iii. 1.17.) Source: Edward Herbert Bunbury, “DAMOCLES (Δαμοκλῆς),” Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1870) 935.

DAMOCLES (Δαμοκλῆς), a Syracusan, one of the companions and flatterers of the elder Dionysius, of whom a well-known anecdote is related by Cicero. Damocles having extolled the great felicity of Dionysius on account of his wealth and power, the tyrant invited him to try what his happiness really was, and placed him at a magnificent banquet, surrounded by every kind of luxury and enjoyment, in the midst of which Damocles saw a naked sword suspended over his head by a single horse-hair—a sight which quickly dispelled all his visions of happiness. (Cic. Tusc. v. 21.) The same story is also alluded to by Horace. (Carm. iii. 1.17.) Source: Edward Herbert Bunbury, “DAMOCLES (Δαμοκλῆς),” Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1870) 935.

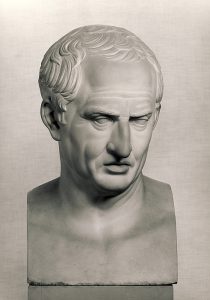

Just so we all have our bearings: Syracuse (today Siracusa) is in Sicily, not upstate New York. Cicero is the extremely famous Roman orator and senator.

Wait – Who is Dionysus?

Dionysus I the Elder was tyrant of Syracuse, a Hellenistic ruler. He lived about 432 to 367 BC. Let’s just say he was not famous for his kindness. In fact, Dante places him in the River Phlegethon made of boiling blood in the Inferno:

“These are the souls of tyrants, who were given

To blood and rapine. Here they wail aloud

Their merciless wrongs. Here Alexander dwells,

And Dionysius fell, who many a year

Of woe wrought for fair Sicily. …” (Harvard Classics 1909)

But, at least in the afterlife, Dionysus gets to suffer forever with his tyrant buddies like Alexander the Great.

Tell us About the Sword

Ok, but we really want to know more about the sword hanging from a single horse hair over the head of Damocles. Damocles was a sycophant–a member of Dionysus’ court who flattered him and enjoyed his largess. Well, sort of. Dionysus was cartoonishly fearful of plotters and assassins–a typical tyrant perhaps. He wouldn’t even let a barber shave him for fear that the razor would “slip”, so he had his daughters burn off his beard with red-hot walnut shells. In order to keep his people on their toes, Dionysus did not take it lightly when Damocles the flatterer paid him some nice compliments about how great his life as tyrant must be. Dionysus, in order to teach Damocles a lesson decided to give him a taste of the tyrant’s life.

He had a huge feast prepared for Damocles, put him on a golden couch, surrounded him with all of the luxuries of the day. And while Damocles was enjoying himself immensely, Dionysus had a sword suspended over his neck, hanging from only a single horse hair. (You might wonder how the geometry works here since we sit in chairs while we eat so a sword could only be suspended over our heads, not necks. But the Greeks and Romans reclined on couches while they ate, so the neck could be an easy target for such a sword.) Needless to say, Damocles found the situation rather uncomfortable and asked to be released from the bizarre situation. Dionysus had the satisfaction of teaching Damocles the lesson of his life: “that there can be no happiness for him over whom some terror is always impending.” That’s the moral of the story.

Let’s Hear it From Cicero

Here is how Cicero himself tells the tale:

When Damocles, one of his flatterers, in talking with him, recounted his forces, his power, the majesty of his reign, the abundance of his possessions, the magnificence of his palace, and said that there had never been a happier man, he replied, ” Damocles, since this life charms you, do you want to taste it yourself, and to make trial of my fortune ? ” He answering in the affirmative, Dionysius commanded the man to be placed upon a golden couch with a covering most beautifully woven and magnificently embroidered, and furnished for him several sideboards with chased silver and gold. Then he ordered boys chosen for their surpassing beauty to stand at the table, and watching his nod, to serve him assiduously. There were ointments, garlands. Perfumes were burned. The tables were spread with the most exquisite viands. Damocles thought himself favored of Fortune. In the midst of this array Dionysius ordered a glittering sword attached to a horse-hair to be let down from the ceiling, so as to hang over the neck of the happy man. After this, Damocles had no eye for the beautiful servants nor for the silver richly wrought, nor did he reach forth his hand to the table. The gar- lands were already fading. At length he begged the tyrant to let him go; for he no longer wanted to be happy. Does not Dionysius seem thus to have declared that there can be no happiness for him over whom some terror is always impending? Yet it was no longer possible for him to return to justice, and to restore to the citizens their liberty and their rights. In his youth, at an improvident age, he had so ensnared himself by wrong-doings, and had committed them to such an extent, that he could not be safe if he began to behave reasonably. (Source: Andrew P. Peabody, trans., Cicero’s Tusculan disputations, [Boston: Little, Brown & Co., 1886] Book V, 21, pp. 286-88)

When Damocles, one of his flatterers, in talking with him, recounted his forces, his power, the majesty of his reign, the abundance of his possessions, the magnificence of his palace, and said that there had never been a happier man, he replied, ” Damocles, since this life charms you, do you want to taste it yourself, and to make trial of my fortune ? ” He answering in the affirmative, Dionysius commanded the man to be placed upon a golden couch with a covering most beautifully woven and magnificently embroidered, and furnished for him several sideboards with chased silver and gold. Then he ordered boys chosen for their surpassing beauty to stand at the table, and watching his nod, to serve him assiduously. There were ointments, garlands. Perfumes were burned. The tables were spread with the most exquisite viands. Damocles thought himself favored of Fortune. In the midst of this array Dionysius ordered a glittering sword attached to a horse-hair to be let down from the ceiling, so as to hang over the neck of the happy man. After this, Damocles had no eye for the beautiful servants nor for the silver richly wrought, nor did he reach forth his hand to the table. The gar- lands were already fading. At length he begged the tyrant to let him go; for he no longer wanted to be happy. Does not Dionysius seem thus to have declared that there can be no happiness for him over whom some terror is always impending? Yet it was no longer possible for him to return to justice, and to restore to the citizens their liberty and their rights. In his youth, at an improvident age, he had so ensnared himself by wrong-doings, and had committed them to such an extent, that he could not be safe if he began to behave reasonably. (Source: Andrew P. Peabody, trans., Cicero’s Tusculan disputations, [Boston: Little, Brown & Co., 1886] Book V, 21, pp. 286-88)

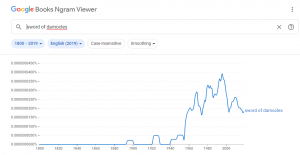

Is the Sword of Damocles on the Rise?

According to Google nGram, peak “sword of Damocles” usage was in 1996. Perhaps I’ve just heard it a lot recently. Maybe if we check back in a few years, we’ll see a new spike in usage of the term. Anyway, there you have it. Now you know what the Sword of Damocles is all about.

New Radio Interview on John 14

Last week, I appeared on “The Good Book Club” at Spirit Catholic Radio. Here’s the clip:

Triduum Videos: Vigils, Suffering and Squirt Guns

FOCUS asked me to record a few videos on topics connected to Holy Thursday, Good Friday and Easter. I hope you enjoy them.

Holy Thursday: Why Pray at Night?

Good Friday: Joining our Sufferings to Jesus

Easter Vigil: Salvation History and Squirt Guns

Recent Interviews

While I might not have been blogging much the past few weeks, I have been very busy with interviews. Here are all the links:

March 2: Polycarp’s Paradigm

February 28: Catholic Review Radio from Archdiocese of Baltimore

February 15

Formed Now: A Bible Study on the Luminous Mysteries – Institution of the Eucharist

January 18: How they Love Mary with Fr. Edward Looney

January 14: The Good Book Club on Spirit Catholic Radio in Omaha, NE

January 6

I appeared on the Cordial Catholic, hosted by K. Albert Little.

Video: “Where Did the Bible Come From?” Interview with Chris Stefanick

I hope you enjoy this little interview with me about “Where Did the Bible Come From?” by Chris Stefanick. It is part of The Search series. It is for a general audience, so expect very introductory material. They did a great job with the lighting and audio here.

What is the Difference Between the RSV-2CE and the ESV Catholic Edition? Statistics Included

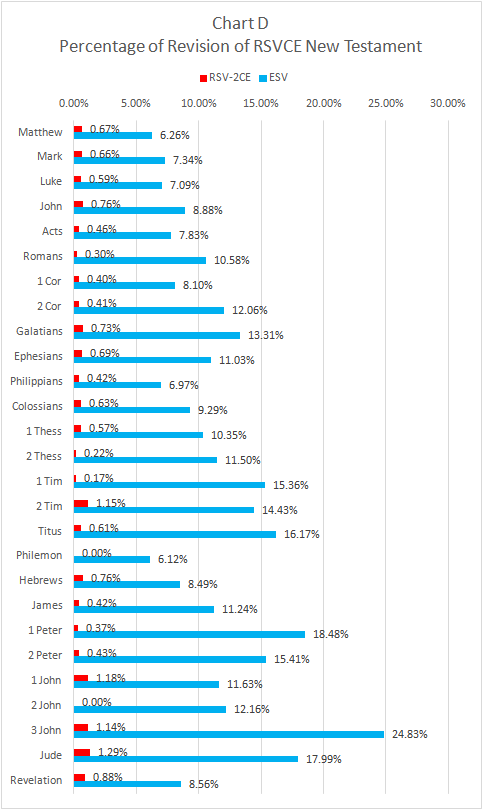

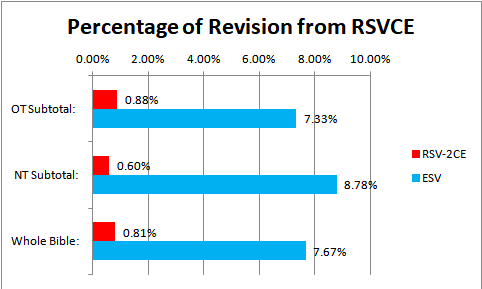

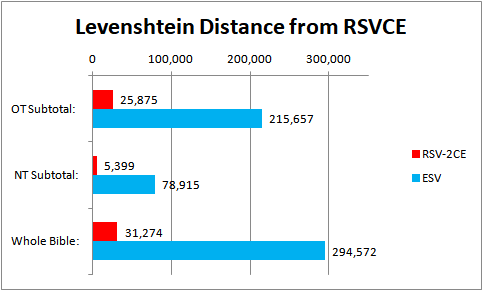

When I tell people about the new ESV Catholic Edition Bible, many of them ask me how it is different from the RSV-2CE. Now, that might leave you scratching your head thinking, “I’ve heard of the RSV and even the NRSV, but what is the RSV-2CE?” So just a bit of backstory before we get to the statistical comparison of the ESV-CE and the RSV-2CE…but here’s a sneak peak at the results:

Backstory

The RSV, which is a revision of the so-called “Standard Version,” aka ASV, came out as New Testament only in 1946 and in full in 1952. But not exactly. That is, the 1952 version only included the books in the Hebrew Bible, not the books in the deuterocanon. It was a Protestant edition, but even so, the translators kept working and released “The Apocrypha” in 1957, which included the deuterocanon. Fair enough, but Lutherans and Anglicans use the deuterocanon, so it was still a Protestant translation until 1965-66 when the “RSV Catholic Edition” was approved in England and released.

The RSV, which is a revision of the so-called “Standard Version,” aka ASV, came out as New Testament only in 1946 and in full in 1952. But not exactly. That is, the 1952 version only included the books in the Hebrew Bible, not the books in the deuterocanon. It was a Protestant edition, but even so, the translators kept working and released “The Apocrypha” in 1957, which included the deuterocanon. Fair enough, but Lutherans and Anglicans use the deuterocanon, so it was still a Protestant translation until 1965-66 when the “RSV Catholic Edition” was approved in England and released.

If I haven’t lost you yet, at the same time that the Catholic Edition was getting approved, the RSV Protestant Edition New Testament was undergoing a revision and that revised Protestant-only RSV NT, the RPRSVNT for short (just kidding), came out in 1971. The translation committee started moving toward a revision of the Old Testament, but that project never materialized. Instead, the Committee turned its attention to the NRSV, which took the place of the RSV in 1990. However, a lot people were not very happy with the NRSV, which is a story for another time. They kept reading their RSV Bibles.

The ESV and the RSV-2CE

Yet even those Bible readers who loved the RSV felt like it needed a touch-up. Two different groups, one Protestant and one Catholic, went back to the RSV to revise it again, but in a different way than the NRSV. Crossway Books, a Protestant publisher, started first in 1999 and completed their revision in 2001—that’s what we now know as the ESV. Ignatius Press, a Catholic publisher, started soon after and published the RSV-2CE in 2006. Now, of course my readers will know, the ESV-CE exists as of 2018. So, how are these two different revisions of the RSV different from one another?

Yet even those Bible readers who loved the RSV felt like it needed a touch-up. Two different groups, one Protestant and one Catholic, went back to the RSV to revise it again, but in a different way than the NRSV. Crossway Books, a Protestant publisher, started first in 1999 and completed their revision in 2001—that’s what we now know as the ESV. Ignatius Press, a Catholic publisher, started soon after and published the RSV-2CE in 2006. Now, of course my readers will know, the ESV-CE exists as of 2018. So, how are these two different revisions of the RSV different from one another?

A Personal Note

It is important to say that though I find myself wrapped up in the publication and promotion of the ESV-CE, I like the RSV-CE and the RSV-2CE as well. In fact, my own writing has appeared and will continue to appear along with the RSV-2CE in publications like the Ignatius Catholic Study Bible and the Augustine Institute’s Bible-in-a-Year. I really just want people to read, study and pray the Bible, regardless of whatever translation or language they are reading it in.

It is important to say that though I find myself wrapped up in the publication and promotion of the ESV-CE, I like the RSV-CE and the RSV-2CE as well. In fact, my own writing has appeared and will continue to appear along with the RSV-2CE in publications like the Ignatius Catholic Study Bible and the Augustine Institute’s Bible-in-a-Year. I really just want people to read, study and pray the Bible, regardless of whatever translation or language they are reading it in.

First, the Similarities

- Both the RSV-2CE and ESV-CE have all the books of the Bible including the deuterocanon.

- Both the RSV-2CE and ESV-CE are revisions of the RSV Bible.

- Both the RSV-2CE and the ESV-CE eliminate archaic language that was included in the RSV: thou, thee, didst, hast, etc.

Second, the Differences

- They have different base texts for the New Testament: The RSV-2CE, being a revision of the 1965-66 RSV-CE, starts with the 1946 RSV New Testament with the few dozen minor modifications made by the Catholic translators (listed in the back of the RSV-CE). The ESV-CE, because it started as a Protestant revision of the Protestant RSV, drew on the 1971 RSV New Testament, not the 1946 New Testament. The ESV-CE thus has one additional layer of updates in the New Testament.

- The RSV-2CE is minor revision, while the ESV-CE is a major revision. Maybe one way to put it is the RSV-2CE is still the RSV. The number of changes is very small and the scope of changes is modest. A large number of the RSV-2CE changes involve updating language to get rid of “thees” and “thous.”

- The ESV-CE is based on updated text-critical information both in the Old and New Testaments, whereas the RSV represents the state of the field in the 1940s and ’50s. Two facts illustrate the point:

- The RSV used the 17th edition of the Nestle-Aland critical edition of the Greek New Testament, while the ESV used the 27th Text-critical knowledge of the text of the NT has improved considerably since the 1940s.

- The RSV-2CE of Tobit relies on the 1957 RSV Apocrypha translation, which was based on the shorter Greek text of Tobit (Greek I represented in Vaticanus and Alexandrinus), while all modern translations of Tobit, like the ESV-CE, rely on the longer Greek text (Greek II represented by Sinaiticus). Greek II is about 1700 words longer than Greek I and it serves as the basis for the Nova Vulgata rendition of Tobit in Latin. Greek II is also confirmed as the best text of Tobit by the 1995 publication of long fragments of Tobit from the Dead Sea Scrolls in Hebrew and Aramaic by Fr. Joseph Fitzmyer, SJ.

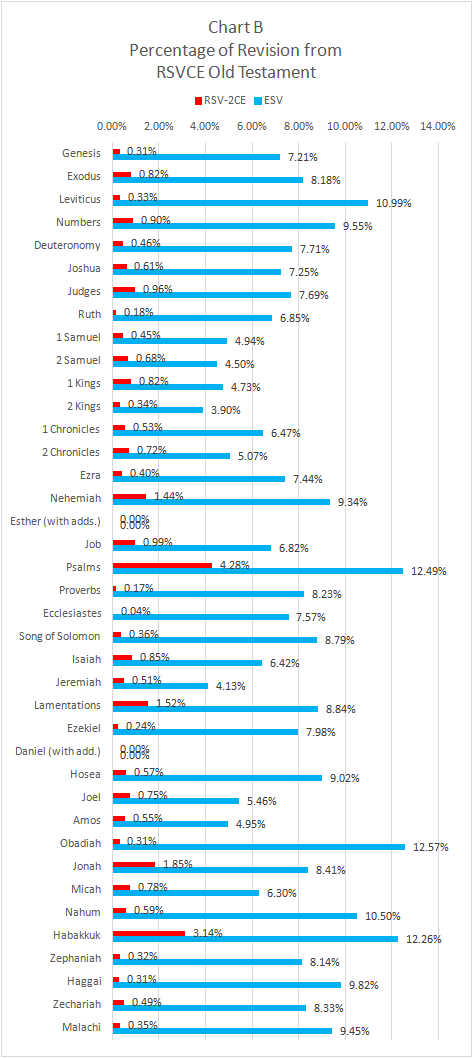

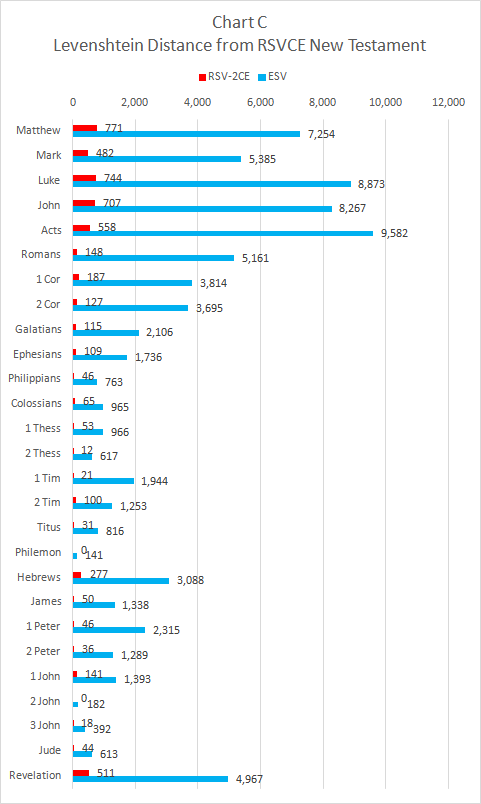

Statistics, Please!

Ok, now the fun part. To illustrate that the ESV-CE is a major revision and the RSV-2CE is a minor revision, one only needs a computer. Rather than reading through the entire Bible and hand-counting every single change, I decided to let the robots do the hard work. But how? By using a little-known idea from computer science called “Levenshtein Distance,” which quantifies “the number of deletions, insertions, or substitutions required” to change one string of text into another string of text.

Methodology

Using the “Bible Text Only” copy tool in Verbum (aka Logos) Bible Software which excludes verse numbers, headings, footnotes and other non-Bible text, I compared the RSV-CE text of every book of the Bible to the RSV-2CE and to the ESV-CE to calculate the Levenshtein Distance as a discreet number, using the calculator at PlanetCalc. Then dividing the Levenshtein Distance by the total number of characters in the RSV-CE text, I was able to arrive at a percentage difference between the RSV-CE and the RSV-2CE, and also the percentage difference between the RSV-CE and the ESV-CE. (Yes, this took a long time and a huge spreadsheet!)

For example, using the super-short Obadiah, we find 3,221 characters in the RSV-CE. The RSV-2CE Levenshtein Distance for Obadiah is only 10, so we have a 0.31% difference. Whereas, the ESV-CE Levenshtein Distance for Obadiah is 405, revealing a 12.57% difference—a far more substantial revision. What I will list in the following tables is the percentage difference from the RSV-CE for every book of the Bible both in the RSV-2CE and in the ESV-CE and the Levenshtein distance for every book of the Bible, comparing both translations. Before we get there, another example might help.

Example: Deuteronomy

Here’s the data for Deuteronomy:

- RSV-CE Bible text characters: 141,082

- RSV-2CE Bible text characters: 141,025

- RSV-2CE Levenshtein Distance from RSV-CE: 654

- ESV Bible text characters: 140,039

- ESV Levenshtein Distance from RSV-CE: 10,883

To get percentages, we use Levenshtein Distance divided by RSV-CE characters:

|

Deuteronomy: |

RSV-2CE | ESV | ||

| Levenshtein Distance: | 654 | Difference:

0.46% |

10,883 |

Difference: 7.71% |

| RSV-CE characters: | 141,082 |

141,082 |

||

This example illustrates how the ESV is a major revision of the RSV, while the RSV-2CE is a minor revision. The ESV has more than sixteen times as many changes as the RSV-2CE in Deuteronomy.

Results: Old Testament, New Testament and Whole Bible in tables and charts

|

Old Testament: |

RSV-2CE | ESV | ||

| Levenshtein Distance | 25,875 | Difference:

0.88% |

215,657 |

Difference: 7.33% |

| RSV-CE characters | 2,940,837 |

2,940,837 |

||

|

New Testament: |

RSV-2CE | ESV | ||

| Levenshtein Distance | 5,399 | Difference:

0.60% |

78,915 |

Difference: 8.78% |

| RSV-CE characters | 898,327 |

898,327 |

||

|

Whole Bible* |

RSV-2CE | ESV | ||

| Levenshtein Distance | 31,274 | Difference:

0.81% |

294,572 |

Difference: 7.67% |

| RSV-CE characters | 3,839,164 |

3,839,164 |

||

*It is worth noting that I’m working from what’s available in the software, and right now that is the ESV-2016, not the current ESV-CE, so my calculations do not yet include the deuterocanonical books (or Esther and Daniel), nor the very few changes have been made between the Protestant and Catholic versions of the ESV.

Overall, we see that the ESV has nine-and-a-half times more changes than the RSV-2CE.

Results: Book by Book

I’m including four charts comparing the RSV-2CE and the ESV:

- Chart A: Levenshtein Distance from RSVCE Old Testament

- Chart B: Percentage of Revision from RSVCE Old Testament

- Chart C: Levenshtein Distance from RSVCE New Testament

- Chart D: Percentage of Revision from RSVCE Old Testament

Observations

- In every book, ESV has substantially more revision than the RSV-2CE.

- RSV-2CE has the most revision in prayer-heavy texts (Psalms, Nehemiah, Habbakuk), where the RSV had lots of things like “thou hast” and “thou didst.” The RSV-2CE seems to focus on eliminating archaic vocabulary.

- In certain short books, the RSV-2CE has no revision (Philemon, 2 John).

- Ezekiel is a stand-out example of the contrast, where RSV-2CE changes only 467 characters, whereas ESV changes 15,380 (about 33 times more revision!).

- The ESV revises more in the NT (8.78%) than in the OT (7.33%), but the RSV-2CE revises more in the OT (0.88%) than in the NT (0.60%).

- The Book of Psalms has the most revisions in both, but that is expected since it is the longest book.

Overall, I hope that this post illustrates the value of the ESV-CE as a more substantial revision of the respected RSV-CE than its close cousin, the RSV-2CE.