Earlier this year, I had the delight of offering a commencement address to the graduating class of Our Lady of Walsingham Academy in Colorado Springs, Colorado. As the fall semester draws to a close, I thought I would share it with you along with some pictures of the event. It was a fun day and so encouraging to see young people launch out into life not knowing what is ahead. I did my best to give them a pep talk. I’ll let you judge the results of that effort in writing.

Commencement Address

Our Lady of Walsingham Academy

Mark Giszczak

May 24, 2025

It is a joy for me to be with all of you today for this celebration. I wish to thank your Headmaster, Andrew Rossi, for inviting me to come. And I want to thank all of you clergy, teachers, parents, guests and friends for supporting our esteemed and worthy graduates to whom I will address my brief remarks.

One day, the second President of the United States, John Adams, was walking down the street when all of a sudden he heard something unexpected—except he had heard the same sound before from the same house: a voice, singing. Intrigued by this unlikely sound, he went looking for the singer. And what did he find? A man, a shoemaker, busy at his work, happily singing as he pounded nails into soles, cut leather and went about his business. The man had a wife and many children, all living together in a single room. Adams asked him if it was difficult making a living and he said, “Sometimes.” But as soon as he had ordered a pair of shoes and left, Adams said “I had scarcely got out the door before he began to sing again like a nightingale.” But Adams reflected later: “Which was the greatest philosopher? Epictetus or this shoemaker?” The great Stoic was fond of saying, “He who is not happy with little will never be happy with much.” Another way he put it when asked “who is the rich man?” Epictetus offered: “He who is content.”

One day, the second President of the United States, John Adams, was walking down the street when all of a sudden he heard something unexpected—except he had heard the same sound before from the same house: a voice, singing. Intrigued by this unlikely sound, he went looking for the singer. And what did he find? A man, a shoemaker, busy at his work, happily singing as he pounded nails into soles, cut leather and went about his business. The man had a wife and many children, all living together in a single room. Adams asked him if it was difficult making a living and he said, “Sometimes.” But as soon as he had ordered a pair of shoes and left, Adams said “I had scarcely got out the door before he began to sing again like a nightingale.” But Adams reflected later: “Which was the greatest philosopher? Epictetus or this shoemaker?” The great Stoic was fond of saying, “He who is not happy with little will never be happy with much.” Another way he put it when asked “who is the rich man?” Epictetus offered: “He who is content.”

In other words, that poor singing shoemaker was the man that we should all aspire to be. He found a way to overcome adversity—yes, with hard work—but with more than that, by the outlook he adopted, the way he chose to be content and cheerful in spite of his circumstances. Just as St. Paul says, “there is great gain in godliness with contentment” (1 Tim 6:6 ESV).

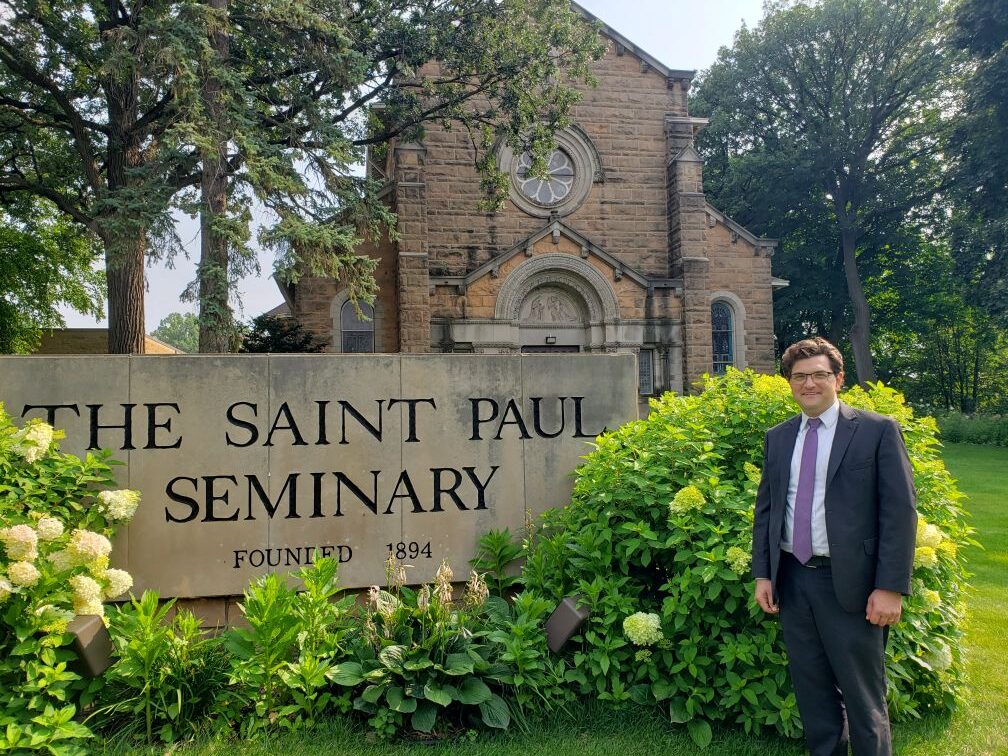

Me and Mr. Rossi in the procession for the graduation ceremony

Now there’s a balance to strike here. We don’t want to become so content that we stand still and do nothing, that we never set goals, work hard to achieve them and wend our way forward. Be we should never become so dissatisfied with the circumstances of our journey that we lose sight of the fact that it is a journey, to become so discontent with the way things are that we become malcontents, holding the present circumstances in contempt because they don’t live up to our expectations. The reality is we make our circumstances. Yes, there are plenty of things outside our control—those are the things we shouldn’t worry about precisely because we cannot control them. But, there are also plenty of things within our control—things that we can change, and those are the things to focus on. What we want is to set our sights high, aim for the best, and not begrudge the uncomfortable parts of the trail to get where we want to go. They are part of the process. Success is not free. It is not easy. Life requires something of us.

But the trouble is, we don’t know what it will require when we set out. The only thing certain is uncertainty. The future is always foggy. We feel blind because we are. We are working and hoping and planning and looking, but rarely are we collecting lots of trophies and hauling in bags of money. No, the way is hard. It is not clear. We do not get a blueprint. Yes, the Lord has a calling on your life, but he doesn’t give you a script. You have to make up your part as it goes along. And besides, he is the Lord of uncertainty: “Foxes have holes and birds of the air have nests, but the Son of Man has nowhere to lay his head” (Luke 9:58 ESV). If you want to follow Jesus, you are following a homeless man who died by execution. It was precisely in his self-sacrifice, his self-abnegation, that he taught us the deepest lesson of love: my life is not about me, it’s about you. Your life is not about you, it’s about everyone else. The only way to find yourself is to give yourself. “Greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends” (John 15:13 KJV). He was the omnipotent Lord of the Universe, but he adopted the humblest possible position in the whole universe: to die as a falsely accused criminal on a cross. He sacrificed everything for us. He taught us what love looks like. He emptied himself, poured himself out for the sake of love.

Mr. Rossi speaking (you can see me sitting in front of the podium)

And that’s thing – thinking will only get you so far. Reading, analyzing, studying, even arguing are all just warmups, precursors to when the rubber hits the road. Action is required. You have to actually do something—to speak those lines, to walk across the stage, to launch out on a career, to open a business, to start climbing at the first rung of the ladder. Hard work is required. It is a first step, a prerequisite, a sine qua non, a necessary condition of success. Yet hard work will not get you all the way. You must be driven by something deeper than desire, deeper than greed or ambition. You must be driven by what drove our Lord—love. Love of God, love of self, love of neighbor. You cannot lay down your life out of love for others if you do not love yourself. You cannot “love others as yourself” if you do not love yourself. We cultivate love of God in prayer. We cultivate love of others in selfless service. We cultivate a healthy and appropriate and necessary love of self by developing habits of virtue: of temperance, prudence, justice and fortitude. You can’t control others, but you can control yourself—only by means of virtue. Those who lack self-control will not climb this mountain. They will not succeed.

The Stoics had a saying for this as well: mens sana in corpore sano—a sound mind in a sound body. Sleep, exercise and healthy eating habits are the foundation of physical health. Physical health is foundation of mental health. Mental health is the foundation of spiritual health. If we do not treat our bodies with care and respect, giving them the nourishment and exercise they require, we will be plagued by dysregulated internal systems, distracted by doctor visits, unable to focus on developing our lives because we are stuck in a state of acedia—unable to cope with life, spiritually sick. Sadly, so many in our generation are stuck—depression, anxiety, substance-abuse, loneliness. But that’s no way to live. There is more to life than complaining about how tough it is. The path ahead is hard—of course it is! That’s not something to sit down and mope about, but it is a chance for us to summon our courage, to press on despite the difficulties, to embrace the challenge and allow it to shape us into the men and women we were meant to be.

Peroration – Quo Vadis?

So this day is a signpost, a landmark, a moment to pause and reflect on everything that has happened before setting out on the new journey ahead. As your time here fades into memory and new paths open before you, I hope that you will take courage that you have been well prepared for the road ahead.

The proud graduating class of Our Lady of Walsingham Academy (and I’m on the far left in the back row)

As we press on into that uncertain future, we should begin with the end in mind. That happy, singing shoemaker, gives us an image of the path. He has not arrived, but he is on the journey. The journey is joyful even when it is hard. It is beautiful because it is ours: the one life, the one brief story that we get to live, the gift that we receive by the very living of it.

Thinking about this journey of life brings me back to that legend about St. Peter fleeing Rome in the midst of a persecution. Along the way out of the city, the Lord appears to him and simply asks him, “Quo vadis? Where are you going?” Peter understood what was implied. He stuck his walking staff in the ground right there and went back into the city to die a glorious martyr’s death. But that question still lingers for us: where are you going? It is a question that can only be answered fully in hindsight, but now, we can get a glimpse, a hint of an answer in conversation with the Lord, seeking his call on our lives, trying to hear his voice inviting us down a certain path, and eventually responding with loving obedience. As we take one step, and then another, the path will become clear, the way will open up. And we can say yes to what the future holds. He has promised to be there with us, “…even to the end of the age” (Matt 28:20).

So, there you have it. I gave a commencement address! It was great to be there with these young people at such a milestone. Who knows where they will end up, but I hope they all find themselves on great paths through life!