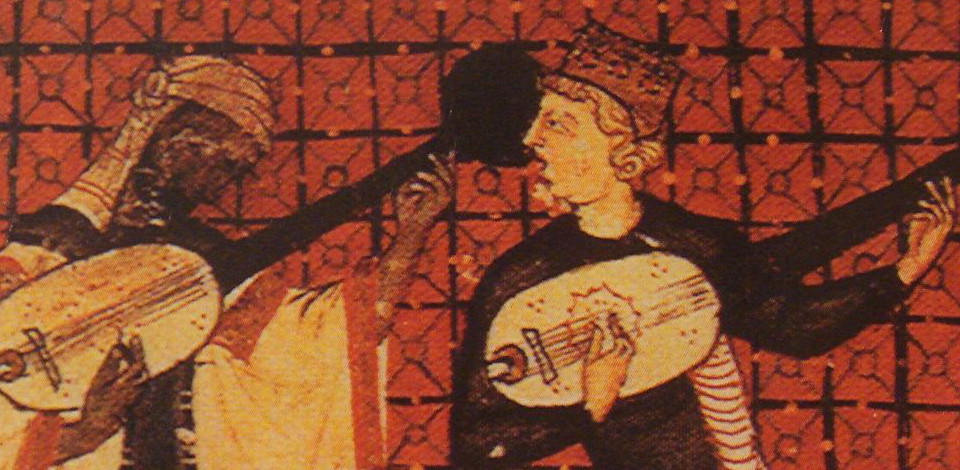

When reading Paul’s encouragements to come together for prayer, you might expect him to recommend speaking aloud. Yet if you read the King James Version or the New American Bible, you would be envisioning something different, a silent experience of communal heart-song. With translation, as always, the devil is in the details, so let’s take a look at them.

The Greek says:

λαλοῦντες ἑαυτοῖς [ἐν] ψαλμοῖς καὶ ὕμνοις καὶ ᾠδαῖς πνευματικαῖς, ᾄδοντες καὶ ψάλλοντες τῇ καρδίᾳ ὑμῶν τῷ κυρίῳ, (Eph 5:19)

I’ve bolded the relevant “te kardia” which is translated differently by different translators. Here are the seemingly silent versions:

Speaking to yourselves in psalms and hymns and spiritual songs, singing and making melody in your heart to the Lord; (Eph 5:19 KJV)

Speaking to yourselves in psalms, and hymns, and spiritual canticles, singing and making melody in your hearts to the Lord; (Eph 5:19 DRA)

addressing one another (in) psalms and hymns and spiritual songs, singing and playing to the Lord in your hearts, (Eph 5:19 NAB)

Speak to one another with psalms, hymns and spiritual songs. Sing and make music in your heart to the Lord, (Eph 5:19 NIV)

speaking to one another in psalms, hymns, and spiritual songs, singing and making music in your hearts to the Lord, (Eph 5:19 NET)

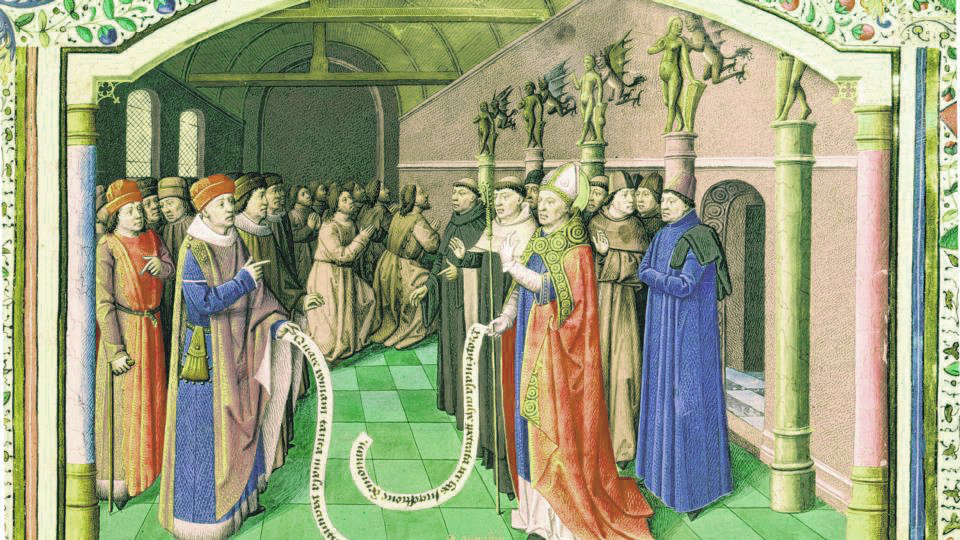

The last time I checked, when you speak or sing “in your heart,” it’s a silent activity. You’ll also notice in the older KJV and DRA that one could take the English “speaking to yourselves” as reflexive and singular, as in “I was talking to myself.” Now both of these concepts are possible: te kardia can mean “in your heart” and heautois can mean “yourselves” in a reflexive way. Yet it seems highly unlikely that Paul would summon the Christian community to speak, sing and make melody in a completely silent fashion, as if we all came together only to inaudibly hum to ourselves. To back me up, I’ll quote Muddiman’s commentary here:

“If pressed, a true reflexive would mean ‘speaking to yourselves’ and the maxim would then be recommending inward praise during the daily life of believers (as, probably, 1 Thess. 5:16f. and Phil. 4:4–6). But the larger context implies corporate worship and interaction with other Christians (and this must be the sense at Col. 3:16, with its ‘teaching and admonishing each other’).” Muddiman, J. (2001). The Epistle to the Ephesians (p. 248). London: Continuum.

Beyond this point, it is important to note that Paul’s conception of the Christian community as the body of Christ (e.g. 1 Cor 12) would cause him to talk about it as a communal entity. That means, when one members speaks to another member, it would really be the “body” talking to itself. Thus he uses the reflexive heautois and not the expected reciprocal pronoun allelon.

Translations with Audible Singing

Some of the more recent translations do a better job here:

addressing one another in psalms and hymns and spiritual songs, singing and making melody to the Lord with all your heart, (Eph 5:19 RSV)

addressing one another in psalms and hymns and spiritual songs, singing and making melody to the Lord with your heart, (Eph 5:19 ESV)

speaking to one another in psalms and hymns and spiritual songs, singing and making melody with your heart to the Lord; (Eph 5:19 NASB)

If you read the RSV, ESV or NASB, you might decide to speak up in church—that is, here Paul recommends speaking, singing and making melody “with your heart” rather than simply “in your heart.” Similarly, the UBS Translation Handbook expresses the confusing array of translations and simply throws up its literary hands:

What follows in Greek is simply “in your heart,” which TEV understands to mean with praise in your hearts. But some translate “in your hearts” (NEB, TNT, NIV, JB), which can only mean inaudible singing; so Westcott: “the outward music was to be accompanied by the inner music of the heart.” But it seems difficult to believe that the writer was telling them to have the strains and choruses of songs and psalms running through their minds. Others translate “from the heart,” “heartily,” “with all your hearts” (Brc, Mft, Gdsp, and others). Abbott, however, notes that the normal way to say this is “from the heart” (see the synonymous “from the soul” in verse 6:6). TEV understands the Greek phrase here to mean “with praise in your heart,” but it may be preferable to take the phrase to mean “with all your heart” (RSV), that is, heartily, enthusiastically. (Bratcher, R. G., & Nida, E. A. [1993]. A handbook on Paul’s letter to the Ephesians [p. 136]. New York: United Bible Societies.)

Paul could either be recommending silent but quasi-musical praise of God in your mind or active, out-loud, enthusiastic, musical praise of God with your mouth and vocal chords. That’s a big difference! But what does that difference depend on?

The Dative Difference

The way we translate either “in” or “with” in this case zeroes on the usage of the dative case. (Definition from Robertson’s grammar: “The dative is the case of personal interest [denoting advantage or disadvantage], corresponding to the English to or for, or indirect object.”) In this particular case we are dealing with the fine distinction between the “dative of manner” and the “dative of means/instrument” (using Daniel Wallace’s categories). The dative of manner describes the way in which an action is performed—as in “whether in pretense or in truth” in Phil 1:18. The dative of means/instrument, however, describes the instrument through which the action of the verb is performed—as in “she wiped his feet with her hair” (John 11:2). I would argue that here in Ephesians 5:19, we are not looking at a dative of manner, where all the singing words are internal and trapped in your heart. Rather, Paul is looking at the heart as a musical instrument of sorts, through which all songs and hymns must go in order to come out of our mouths. This usage would be a dative of means/instrument. He is not envisioning a crowd of Christians speaking to themselves quietly and humming tunes soundlessly, but of Christians gathered together and speaking and singing out loud. So next time you come together with other Christians for worship, make sure to open your mouth and sing!

At the first, all of this new information that’s pouring forth in study after study and book after book seems totally harmless, interesting and even fun. I mean, who wouldn’t want to know what makes their prefrontal cortex “light up”? And, even from an ethical standpoint, as long as the scientists are just looking, no harm is done. But it will not be long before they go from passive bystanders, merely peering into the brain, to in fact being able to manipulate the brain for their own purposes. To me, the prospect of decoding the brain, much like scientists have decoded DNA, has serious repurcussions from an ethical standpoint. Now, I realize that what I’m talking about might sound like science fiction right now, but in a few years, with a few scientific leaps forward, we will arrive at a brave new world not of brain scanning, but of brain programming. If the neuropsychologists decode the brain sufficiently, then they will be able to hack it–and who could resist the temptation? Here are my chief ethical worries about what lies ahead:

At the first, all of this new information that’s pouring forth in study after study and book after book seems totally harmless, interesting and even fun. I mean, who wouldn’t want to know what makes their prefrontal cortex “light up”? And, even from an ethical standpoint, as long as the scientists are just looking, no harm is done. But it will not be long before they go from passive bystanders, merely peering into the brain, to in fact being able to manipulate the brain for their own purposes. To me, the prospect of decoding the brain, much like scientists have decoded DNA, has serious repurcussions from an ethical standpoint. Now, I realize that what I’m talking about might sound like science fiction right now, but in a few years, with a few scientific leaps forward, we will arrive at a brave new world not of brain scanning, but of brain programming. If the neuropsychologists decode the brain sufficiently, then they will be able to hack it–and who could resist the temptation? Here are my chief ethical worries about what lies ahead: But what if, after this technique has been perfected, a new patient arrives in Dr. Brain’s office and says, “Doc, I’ve got a hard life. Things haven’t worked out so well for me. I have a terrible job that I hate, but I know I need to stick with it for the sake of my family. Can you help me?” At this point, it would be very tempting for Dr. Brain to tinker with the patient’s will so that the patient wants to stick with the job that he actually hates. Perhaps the doctor can even cause him to like it.

But what if, after this technique has been perfected, a new patient arrives in Dr. Brain’s office and says, “Doc, I’ve got a hard life. Things haven’t worked out so well for me. I have a terrible job that I hate, but I know I need to stick with it for the sake of my family. Can you help me?” At this point, it would be very tempting for Dr. Brain to tinker with the patient’s will so that the patient wants to stick with the job that he actually hates. Perhaps the doctor can even cause him to like it. Next, if they decode the brain, the scientists could tinker with our memories. It would start with noble therapies like lessening the impact of painful memories for PTSD patients or those with a traumatic childhood. Yet if they become truly capable of erasing memories from our brains, look out! A person could go to an unscrupulous brain doctor and ask that their memory be wiped of unpleasant memories like their last dating relationship or their bad debts or their failures as a child. Again, while such a technology could be used for the good, it could also lead down a dark path. What if oppressive governments could wipe revolutionary memories from citizens or use memory-wiping as a punishment for crimes?

Next, if they decode the brain, the scientists could tinker with our memories. It would start with noble therapies like lessening the impact of painful memories for PTSD patients or those with a traumatic childhood. Yet if they become truly capable of erasing memories from our brains, look out! A person could go to an unscrupulous brain doctor and ask that their memory be wiped of unpleasant memories like their last dating relationship or their bad debts or their failures as a child. Again, while such a technology could be used for the good, it could also lead down a dark path. What if oppressive governments could wipe revolutionary memories from citizens or use memory-wiping as a punishment for crimes? It is possible, even now, to get your entire genome sequenced.

It is possible, even now, to get your entire genome sequenced.  In this fictive future we are imagining a world in which scientists have successfully decoded the brain, found a way to download its data into a computer file. But surely, if they are able to accomplish all of this, then they will make a way to upload to the brain. Just imagine a micro-USB port behind your left ear. Again, on the one hand, this sounds rather nice. If you wanted to learn Japanese or read Moby Dick, all you’d have to do is plug in for a second or two and–presto!–you’ve got it in your mind.

In this fictive future we are imagining a world in which scientists have successfully decoded the brain, found a way to download its data into a computer file. But surely, if they are able to accomplish all of this, then they will make a way to upload to the brain. Just imagine a micro-USB port behind your left ear. Again, on the one hand, this sounds rather nice. If you wanted to learn Japanese or read Moby Dick, all you’d have to do is plug in for a second or two and–presto!–you’ve got it in your mind. Rather than simply wiping away bad memories, you could upload good ones. If you had a bad childhood, that could be swapped out for a good one in your memory. If you didn’t get to take a vacation, you could upload one to your brain. The possibilities are endless!

Rather than simply wiping away bad memories, you could upload good ones. If you had a bad childhood, that could be swapped out for a good one in your memory. If you didn’t get to take a vacation, you could upload one to your brain. The possibilities are endless!