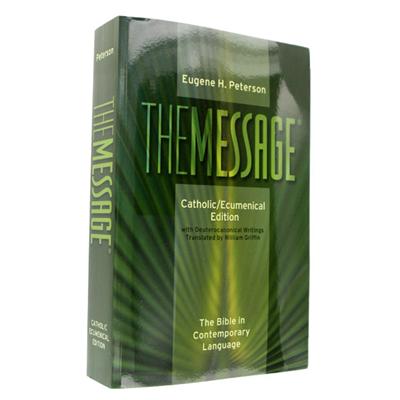

I just received a copy of the new Catholic/Ecumenical Messsage Bible from the publisher. It came out in 2013, so I have no idea why they’re promoting it right now. This book includes Protestant seminary-professor-turned-pastor Eugene Peterson’s very loose translation of the Protestant canon and a new translation of the deuterocanon by the Catholic William Griffin.

The Message and Canon Law

I have to say the first thing that struck me was the blurbs on the back include two Catholic priests and an Episcopalian bishop. Notably absent was the endorsement of a Catholic bishop. That’s probably because under Canon Law Catholic Bibles are supposed to be approved by the national bishops’ conference. In the case of the U.S., that means the USCCB. The relevant canons are as follows:

Can. 825 §1. Books of the sacred scriptures cannot be published unless the Apostolic See or the conference of bishops has approved them. For the publication of their translations into the vernacular, it is also required that they be approved by the same authority and provided with necessary and sufficient annotations.

2. With the permission of the conference of bishops, Catholic members of the Christian faithful in collaboration with separated brothers and sisters can prepare and publish translations of the sacred scriptures provided with appropriate annotations.

These laws mean that a private Catholic individual is not supposed to publish his own translation of the Bible without appropriate ecclesiastical permission, even if that person is working on a Bible-publishing project in conjunction with Protestants.

When I asked the publisher of this Catholic/Ecumenical Message about this, I was told that they didn’t feel the need to request permission from the USCCB because the Message is a a “paraphrasal translation” only meant to supplement more formal translations. But in fact, Eugene Peterson is no slouch in biblical languages. He used to teach Greek and Hebrew and so the Message is not really a paraphrase at all, but a very, very loose (like spaghetti-noodle-knot-loose) translation of the original languages.

Canon law does not grant a dispensation, exception or legal loophole in the approval process to “informal” or “paraphrasal” translations of the Bible. Beyond that, since 1984, canon law has insisted that Catholic Bibles have “necessary and sufficient annotations.” That doesn’t mean that every Bible has to be a 3,000 page study Bible, but that Bibles do need to include some notes on the difficulties and obscurities in the text, particularly at places where people could easily get confused. The New American Bible, the Jerusalem Bible and even the RSV-CE provide these types of annotations.

Now, I’m no canon lawyer, but I must admit I do have misgivings about the publication of this “Catholic/Ecumenical Message” Bible without the approval of the bishops’ conference and with no imprimatur (The imprimatur indicates ecclesiastical approval for other religious books and is different from a bishops’ conference’s approval of a Bible translation).

The Message and Original Languages

While Eugene Peterson translated from the original languages, the Catholic scholar who translated the deuterocanon, William Griffin, chose a different tack. I’ll give it to you in his own words:

For my primary text, I could have used the Hebrew or, where necessary, the Greek manuscripts; but I didn’t. As I’ve already indicated, they seem to me to be the exclusive possession of the biblical scholars. Instead, I chose the Latin Vulgate—not the one put together by Jerome in the fourth century, but the revised and expanded edition called Nova Vulgata (New Vulgate) published in 1998.

Pope John Paul II wrote a brief preface to that translation in which he declared and proclaimed that the Nova Vulgata may be used as the authentic text when translating into English, especially in the Sacred Liturgy. And so that’s what I used.

Um, well, this is an interesting perspective, but I cannot agree with it. While Latin is the liturgical language of the Western Chruch, none of the Bible was written in Latin, so it’s a bit tendentious to suggest that it’s the best source for our vernacular translations.

Griffin refers to this little line in John Paul II’s Scripturarum Thesaurus (Apr 25, 1979):

This New Vulgate edition will also be of such a nature that vernacular translations, which are destined for liturgical and pastoral use, may be referred to it.

This line does not make the Nova Vulgata the base text for new Bible translations. It certainly does not override earlier magisterial statements about the importance of going back to the original languages. In fact, the Vatican has repeatedly encouraged the study of original languages and has often mandated that all vernacular translations of Scripture start with the Greek and Hebrew.

Pope Pius XII in Divino Afflante Spiritu (Sep 30, 1943) insisted on the primacy of the original languages:

…therefore ought we to explain the original text which, having been written by the inspired author himself, has more authority and greater weight than any even the very best translation, whether ancient or modern…

Pius XII is gentle in his mode of expression, but he’s basically saying that the original Greek and Hebrew texts of Scripture trump the Latin Vulgate (an “ancient translation”). His encyclical set off a tidal wave of new translations from the original languages.

Dei Verbum from Vatican II takes a similar line:

…the Church by her authority and with maternal concern sees to it that suitable and correct translations are made into different languages, especially from the original texts of the sacred books…

A pope and a Council both point to biblical translation from the original languages. Most Catholic Bibles now published all draw from Greek and Hebrew directly.

Late in the pontificate of John Paul II, a further instruction on translation for liturgical purposes was given. This document, Liturgiam authenticam (Mar 28, 2001), mandates:

Furthermore, it is not permissible that the translations be produced from other translations already made into other languages; rather, the new translations must be made directly from the original texts, namely the Latin, as regards the texts of ecclesiastical composition, or the Hebrew, Aramaic, or Greek, as the case may be, as regards the texts of Sacred Scripture.Furthermore, in the preparation of these translations for liturgical use, theNova Vulgata Editio, promulgated by the Apostolic See, is normally to be consulted as an auxiliary tool, in a manner described elsewhere in this Instruction, in order to maintain the tradition of interpretation that is proper to the Latin Liturgy.

In case there was any lack of clarity on this point, the Congregation for Divine Worship (Nov 5, 2001) issued a letter where they further clarified the mandate

Given the nature of certain statements that have entered the public domain through articles, internet postings and the like, the scope for misunderstanding of the Instruction on the basis of a superficial reading has unfortunately increased. Indeed, some even seem to have reached the erroneous conclusion that the Instruction insists on a translation of the Bible from the Latin Nova Vulgata rather than from the original biblical languages. Such an interpretation is contrary to the Instruction’s explicit wording in n. 24, according to which all texts for use in the Liturgy “must be made directly from the original texts, namely the Latin, as regards the texts of ecclesiastical composition, or the Hebrew, Aramaic, or Greek, as the case may be, as regards the texts of Sacred Scripture”. The Instruction in fact provides a clearer statement on the use of the original biblical texts as the basis for liturgical translation than the norms previously published in the Instruction Inter Oecumenici, n. 40a, published on 26 September 1964 (Acta Apostolicae Sedis 56 [1964] 885).

The point of piling up all these quotations is to say that the Catholic approach to Bible translation is to go back to Greek and Hebrew and then translate directly into the vernacular. The Nova Vulgata is helpful for indicating which books are to be included and which verses (where there are textual problems), it serves as the norm for traditional liturgical formulation, but it does not serve as the basis for new translations and it has not been commended to us as such by the magisterium. In fact, quite the opposite! Catholics should be reading Bibles translated from Greek and Hebrew.

The Message and Translation Philosophy

I readily admit that there are different legitimate translation philosophies and goals. They are usually put on a spectrum between the woodenly literal (like the NASB) and dynamic equivalence (Jerusalem). Usually in a separate category are the paraphrases like the Living Bible, which is truly a paraphrase of an English translation (the ASV). The Message tries to walk the line between paraphrase and dynamic equivalence. The point is to deliver to modern readers an intelligible, readable Bible that makes more sense than the supposedly clunky language of a typical Bible translation. Even Eugene Peterson did not want The Message to replace other translations or even to be read aloud in church services. He intended it as a study tool.

Just to give you a sense for how The Message upends traditional Catholic phrasing of biblical passages for a rather underwhelming “something else.” Take a look at the angel Gabriel’s greeting to theVirgin Mary:

The Message |

RSV (for comparison) – Luke 1:28 |

Good morning!You’re beautiful with God’s beauty,

|

Hail,full of grace,the Lord is with you! |

Need I say more?

The Catholic/Ecumenical Message does not carry ecclesiastical approval, translates the deuterocanonical books from a Latin translation and embraces a dubious translation philosophy. I’d spend your next Amazon gift card on something else.

Oh, and if you do need a very simplistic translation for a young person or someone who has trouble with English, take a look at the Good News Translation (also known as Today’s English Version) or the Contemporary English Version, both from the American Bible Society and both with ecclesiastical approval from the USCCB.

Thanks Mark for informing us about “Message”. The fact that it is “catholic ecumenical” needs to be pondered in context of other ecumenical indicators in the Church. We already have good reliable Catholic Bibles. Hopefully many will stick with these.

It’s official, we now need to reformulate the Ave Maria.

“Good morning Mary, you’re beautiful with God’s beauty, beautiful inside and out. God be with you. You’re so blessed among women, and the babe in your womb, also blessed! O beautiful Mary, pray for us naughty badboys, now and at the time of our passing.”

So much better than that stuffy old Ave we’re so used to! Wink wink

Sorry for this late comment but in perusing the Nova Vulgata of Esther I noticed that not one single English translation conforms to the canonical text of Esther’s prayer except for The Message, since the NV was itself the basis for the deuterocanonical work. Every other English Bible (please correct me if I’m wrong!) uses a non-canonical source for this prayer, generally LXX-ish. (In this case, it appears that the original source preferred by the NV was actually old Latin and not Greek or Hebrew!) I’m all for the approval process, but hasn’t it been far too loose? Approved translations have notes like “Jonah didn’t actually get swallowed by a fish” (cf NCB) while the Roman Martyrology specifically called out the fish as historical in the 2001 revision that was supposed to get rid of fables… and, incidentally, the “canonical” prayer of Esther (reflected only in The Message!) also recalls Jonah’s episode as historical.