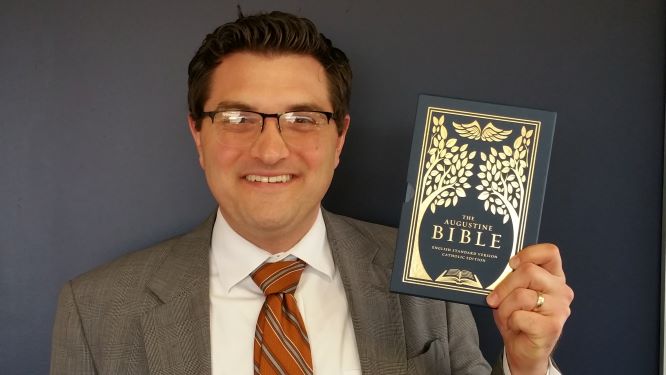

In the promulgation of the new ESV-Catholic Edition, I’ve heard a lot of Internet chatter about various Bible versions in English. Many English-speakers have their favorite translation and will defend it to the hilt. I’d prefer everyone simply learn Greek and Hebrew, but since that’s not likely to happen anytime soon, we’re stuck with vernacular translations. Translation, by its nature, is an imperfect science.

Read the Bible

Ok, wait–before going any further, I’ll just say that I’d much prefer that everyone simply read the Bible a lot in whatever translation they find useful! So if you like the RSVCE, the RSV2CE, the NABRE, the ESVCE, the Douay-Rheims, the JB, the NJB, the RNJB or whatever, keep on reading the Word of God and don’t give up. This book will transform your life. Translation concerns are secondary to the actual practice of reading the Bible.

Back in Time

It is too easy to over-simplify the history of the Bible in English with quick notes like, King James 1611 and Douay-Rheims 1610, but such notes are misleading. Bible translations are big, years-long processes involving lots of people and places. Over time, whether we like it or not, the editions actually printed vary and change whether deliberately or not. The Douay-Rheims Bible, lauded by some as the best Catholic translation, started with a New Testament in 1582, and then an Old Testament in 1610, but it was later substantially revised by Bishop Richard Challoner in the 1700’s. It was translated from the Latin Vulgate of St. Jerome in the Clementine edition. Unexpectedly, Bishop Challoner was often revising the text of the Bible in order to conform to the King James Version familiar to all English-speakers. An American bishop, Francis P. Kenrick, launched his own revision of the Douay-Rheims in the 1850’s and its New Testament was published in 1862 shortly before his death. The American bishops debated making this version the new standard, but eventually the idea was abandoned. (See Gerald P. Fogarty, S.J., American Catholic Biblical Scholarship [San Francisco: Harper & Row 1989] 14-34).

It is too easy to over-simplify the history of the Bible in English with quick notes like, King James 1611 and Douay-Rheims 1610, but such notes are misleading. Bible translations are big, years-long processes involving lots of people and places. Over time, whether we like it or not, the editions actually printed vary and change whether deliberately or not. The Douay-Rheims Bible, lauded by some as the best Catholic translation, started with a New Testament in 1582, and then an Old Testament in 1610, but it was later substantially revised by Bishop Richard Challoner in the 1700’s. It was translated from the Latin Vulgate of St. Jerome in the Clementine edition. Unexpectedly, Bishop Challoner was often revising the text of the Bible in order to conform to the King James Version familiar to all English-speakers. An American bishop, Francis P. Kenrick, launched his own revision of the Douay-Rheims in the 1850’s and its New Testament was published in 1862 shortly before his death. The American bishops debated making this version the new standard, but eventually the idea was abandoned. (See Gerald P. Fogarty, S.J., American Catholic Biblical Scholarship [San Francisco: Harper & Row 1989] 14-34).

The Origin of the Catholic Biblical Association

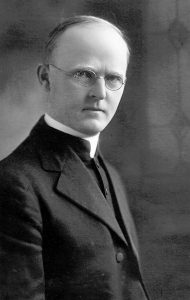

The need for a new Catholic Bible translation for the American Church was never abandoned. Indeed, it resurfaced in the 1930’s. Bishop Edwin Vincent O’Hara of Great Falls, MT organized an editorial board for a revision of the Challoner-Rheims edition, which invited all Catholic Scripture scholars to a meeting in New York for October 3, 1936 (Fogarty, 201). The meeting helped launch the Catholic Biblical Association, which produced a revision of the New Testament, published in 1941, the “Confraternity edition” (Fogarty, 206). Eventually, in light of Divino Afflante Spiritu and Dei Verbum, as I will explain below, the project of revising the Challoner-Rheims edition was abandoned and a completely new translation from the original languages was begun.

The need for a new Catholic Bible translation for the American Church was never abandoned. Indeed, it resurfaced in the 1930’s. Bishop Edwin Vincent O’Hara of Great Falls, MT organized an editorial board for a revision of the Challoner-Rheims edition, which invited all Catholic Scripture scholars to a meeting in New York for October 3, 1936 (Fogarty, 201). The meeting helped launch the Catholic Biblical Association, which produced a revision of the New Testament, published in 1941, the “Confraternity edition” (Fogarty, 206). Eventually, in light of Divino Afflante Spiritu and Dei Verbum, as I will explain below, the project of revising the Challoner-Rheims edition was abandoned and a completely new translation from the original languages was begun.

But what about the Vulgate?

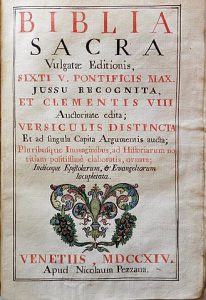

The Vulgate, the Latin translation of St. Jerome, was preserved and printed in many editions. It really became its own textual stream in the tradition of biblical manuscripts, but was somewhat codified by the Sixto-Clementine Edition of 1592. It’s important to note that this edition replaced the 1590 Vulgata Sixtina hastily prepared by Pope Sixtus V, who was apparently still making changes after it went to press with his approval in the bull Aeternus Ille. This edition was forcefully recalled by Pope Clement VIII early in his papacy and replaced by the new Sixto-Clementine edition. If you seek out a Vulgate today, I’d recommend checking out the critical edition from the United Bible Societies. The official Sixto-Clementine Vulgate has been replaced by the Nova Vulgata (1979), which “is the point of reference as regards the delineation of the canonical text” (Liturgiam authenticam, sec. 37).

The Vulgate, the Latin translation of St. Jerome, was preserved and printed in many editions. It really became its own textual stream in the tradition of biblical manuscripts, but was somewhat codified by the Sixto-Clementine Edition of 1592. It’s important to note that this edition replaced the 1590 Vulgata Sixtina hastily prepared by Pope Sixtus V, who was apparently still making changes after it went to press with his approval in the bull Aeternus Ille. This edition was forcefully recalled by Pope Clement VIII early in his papacy and replaced by the new Sixto-Clementine edition. If you seek out a Vulgate today, I’d recommend checking out the critical edition from the United Bible Societies. The official Sixto-Clementine Vulgate has been replaced by the Nova Vulgata (1979), which “is the point of reference as regards the delineation of the canonical text” (Liturgiam authenticam, sec. 37).

Translating to English from the Vulgate?

Most English-speaking Catholic authorities in the nineteenth century took it for granted that Catholic Bible translations into the vernacular be made from the Latin Vulgate. They were ignoring, perhaps, Bishop Challoner’s revisions of the Douay, which brought it more in line with the King James (translated from Greek and Hebrew). Even in 1859, a Catholic reviewer named Orestes Brownson would argue that “There is nothing in the decree of the Council of Trent, that requires our English translations to be made from the Vulgate…and a translation made directly from the original tongues into English will always be fresher, and represent the sense with its delicate shades, far better than a translation made from them through the Latin” (Brownson’s Quarterly Review; Fogarty, 22-23). While Brownson might have been prescient, he was ahead of his time.

Most English-speaking Catholic authorities in the nineteenth century took it for granted that Catholic Bible translations into the vernacular be made from the Latin Vulgate. They were ignoring, perhaps, Bishop Challoner’s revisions of the Douay, which brought it more in line with the King James (translated from Greek and Hebrew). Even in 1859, a Catholic reviewer named Orestes Brownson would argue that “There is nothing in the decree of the Council of Trent, that requires our English translations to be made from the Vulgate…and a translation made directly from the original tongues into English will always be fresher, and represent the sense with its delicate shades, far better than a translation made from them through the Latin” (Brownson’s Quarterly Review; Fogarty, 22-23). While Brownson might have been prescient, he was ahead of his time.

Later, in 1934, the Dutch bishops asked Rome about whether a translation from the original languages of Scripture, not the Vulgate, could be read in liturgy and the response from the Pontifical Biblical Commission (AAS 26, 1934, p. 315-warning! giant PDF!) was negative. Fogarty insists that this is “the first time” that the Vatican weighed in on the side of vernacular translations of the Vulgate over against translations from the original languages (p. 200). Whether he is right not, I’m not sure, but it would become a moot point in under ten years.

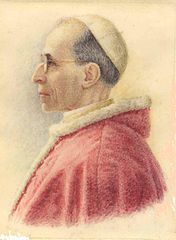

Pius XII and Original Languages — 1943-44

In 1943, Pope Pius XII would publish the encyclical Divino Afflante Spiritu, (drafted by Augustine–later Cardinal–Bea) where he would encourage translations directly from the original languages with the following sentences:

In 1943, Pope Pius XII would publish the encyclical Divino Afflante Spiritu, (drafted by Augustine–later Cardinal–Bea) where he would encourage translations directly from the original languages with the following sentences:

22. Wherefore this authority of the Vulgate in matters of doctrine by no means prevents – nay rather today it almost demands – either the corroboration and confirmation of this same doctrine by the original texts or the having recourse on any and every occasion to the aid of these same texts, by which the correct meaning of the Sacred Letters is everywhere daily made more clear and evident. Nor is it forbidden by the decree of the Council of Trent to make translations into the vulgar tongue, even directly from the original texts themselves, for the use and benefit of the faithful and for the better understanding of the divine word, as We know to have been already done in a laudable manner in many countries with the approval of the Ecclesiastical authority.

Just before this encyclical was released, the Pontifical Biblical Commission issued a clarification of its 1934 response cited above. This clarification (AAS 35, 1943, pp. 270-71–warning! giant PDF!) explicitly granted permission for biblical translations from the original languages. Taking its cue from this clarification from the Biblical Commission and from the new encyclical, the Catholic Biblical Association decided at its meeting in August 1944 at Notre Dame to abandon the project of revising the Challoner-Rheims edition and instead launched a new project to translate the whole Old Testament from the original Hebrew and Greek. This project would eventually become the New American Bible.

The CBA was additionally encouraged and congratulated on pursuing this project by the apostolic delegate, Archbishop Cicognani (his letter was published in Catholic Biblical Quarterly 6 [October, 1944] 389-90: https://www.jstor.org/stable/43723781). The Archbishop lauds the CBA for its efforts, acknowledging that the association is “translating the Old Testament from the original languages into English” and that “This news is a source of great pleasure, since the deep learning which forms the background of their work, and their well-known devotion to the Holy See are already in themselves auguries of success in the monumental work to which they have so resolutely set themselves.” Later in the letter, he nods in the direction of Rome, showing his interpretation of Divino: “Conformably to the recommendations of His Holiness, the members of the Catholic Biblical Association are laudably engaged in translating the Old Testament from the original languages for the use of the laity.” Here we see that the Roman trend in the direction of the original languages is affirmed and made more explicit by the Archbishop.

The CBA was additionally encouraged and congratulated on pursuing this project by the apostolic delegate, Archbishop Cicognani (his letter was published in Catholic Biblical Quarterly 6 [October, 1944] 389-90: https://www.jstor.org/stable/43723781). The Archbishop lauds the CBA for its efforts, acknowledging that the association is “translating the Old Testament from the original languages into English” and that “This news is a source of great pleasure, since the deep learning which forms the background of their work, and their well-known devotion to the Holy See are already in themselves auguries of success in the monumental work to which they have so resolutely set themselves.” Later in the letter, he nods in the direction of Rome, showing his interpretation of Divino: “Conformably to the recommendations of His Holiness, the members of the Catholic Biblical Association are laudably engaged in translating the Old Testament from the original languages for the use of the laity.” Here we see that the Roman trend in the direction of the original languages is affirmed and made more explicit by the Archbishop.

Consilium 1964

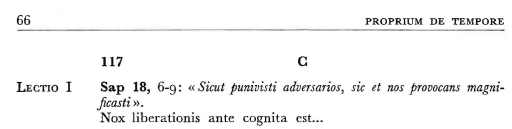

This direction was affirmed, albeit softly, by the Sacred Congregation of Rites in its document, Inter Oecumenici (Sept 26, 1964), 40.a:

The basis of the translations is the Latin liturgical text. The version of the biblical passages should conform to the same Latin liturgical text. This does not, however, take away the right to revise that version, should it seem advisable, on the basis of the original text or of some clearer version.

This slim legal language emphasizes the importance of the Vulgate, but defers to the original languages for revision.

Dei Verbum 1965

The Second Vatican Council weighed in on the side of translating Scripture from the original languages:

“the Church by her authority and with maternal concern sees to it that suitable and correct translations are made into different languages, especially from the original texts of the sacred books” (Dei Verbum, sec. 22)

This statement by the Council affirms that the hierarchy was moving away from Vulgate-only translations toward focus on the original languages.

Liturgiam authenticam 2001

Pope St. John Paul II’s document, Liturgiam authenticam, will actually cite the 1964 law in extending the legal requirement to mandate that all biblical translations be made from the original languages, not from other translations.

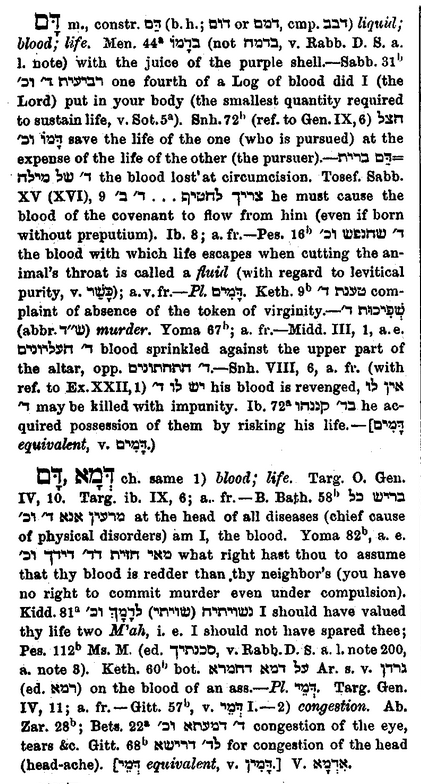

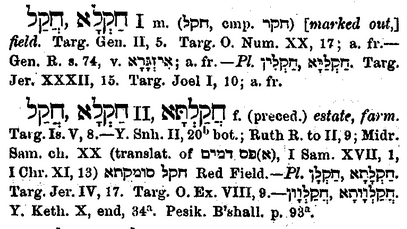

Furthermore, it is not permissible that the translations be produced from other translations already made into other languages; rather, the new translations must be made directly from the original texts, namely the Latin, as regards the texts of ecclesiastical composition, or the Hebrew, Aramaic, or Greek, as the case may be, as regards the texts of Sacred Scripture.

One might think that this instruction contradicts the very idea of JPII launching the Nova Vulgata in 1979, but the document anticipates such concerns, saying, “Furthermore, in the preparation of these translations for liturgical use, the Nova Vulgata Editio, promulgated by the Apostolic See, is normally to be consulted as an auxiliary tool, in a manner described elsewhere in this Instruction, in order to maintain the tradition of interpretation that is proper to the Latin Liturgy.” So the Nova Vulgata is normative for 1.) finding the canonical verses in the original language and for 2.) understanding the proper tradition of interpretation for the Latin Liturgy. However, it does not serve as the basis for the translations, but only as “an auxiliary tool.” Though it is true that Pope Francis issued a Motu proprio in 2017 which limits the application of Liturgiam authenticam, it seems to have little effect on the topic here.

Conclusions

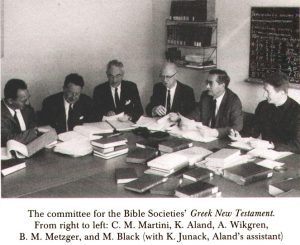

The complex task of Bible translation cannot be distilled down to any one principle. Indeed, any good translator should have respect for all of the available textual traditions, whether Hebrew, Greek, Latin, Syriac, or otherwise, and have a good sense for the strengths and weaknesses of each tradition. In previous eras, access to good instruction in the original languages was scare, but now much more common. Also, good manuscripts and critical editions were harder to come by, but now they can be readily had in libraries and on the Internet. Much of the text-critical work being done in older editions of the Vulgate has been transferred to the guild of text critical scholars of the Greek New Testament (one thinks immediately of the committee put together by Kurt Aland). The relative values of the Masoretic text and the Septuagint have not yet been fully ironed out and I imagine biblical scholars will be arguing about which should have priority until the sun sets on history. Yet from the above historical overview, we can see very clearly that the Catholic Church has been moving away from a Vulgate-only translation philosophy and toward a legal requirement that all biblical translations be made directly from the original languages. But again, whatever translation you are using: Read the Bible!